Artist Hannah Sawtell explores our relationship to consumption, access to technology and the excesses of the Internet Age in an uncompromising exhibition at Southend-on-Sea’s newest gallery.

Over the past half-decade an interesting dichotomy has emerged within the creative industries. On the one hand, the internet has provided a globally connected culture, where consumption, albeit of products or ideas, is international and voracious. Simultaneously ‘craft’ and ‘making’ have become essential buzzwords, with many designers exploring artisanal or handmade avenues of production, and big brands using this kind of vocabulary to package their goods. It’s this global/local, mass-consumed/locally made split that has preoccupied artist Hannah Sawtell over the past few years, primarily using video and digital artworks to explore our relationship to consumption, access to technology and the excesses of the Internet Age. Her new exhibition #STANDARDISER at the recently opened Focal Point Gallery in Southend is a collection of Sawtell’s recent pieces made using the internet as a reference point, ranging from the screen-based works for which she is best known to small-scale sculptures (made in collaboration with local artisans) and a double edition of her publication series Broadsheets.

Focal Point’s Gallery 1 hosts an installation by Sawtell that combines video, industrial and sound design. A large hanging screen (custom-made by Sawtell using bullet-proof glass) depicts a split computer-generated image – half shows a concrete cooling tower surrounded by wind turbines, the other half a a proposal for a luxury Norwegian hotel built in the shape of a snowflake and dripping with crude oil. Striking reminders of the oil industry local to the gallery along the Thames Estuary, neither image is straightforward. The tiny wind turbines look small and ineffectual compared to the dominance of the imposing cooling tower and the river of oil is seductive in its viscosity. Polluting and dirty fossil fuels may be but there is something alluring in our dependent consumption.

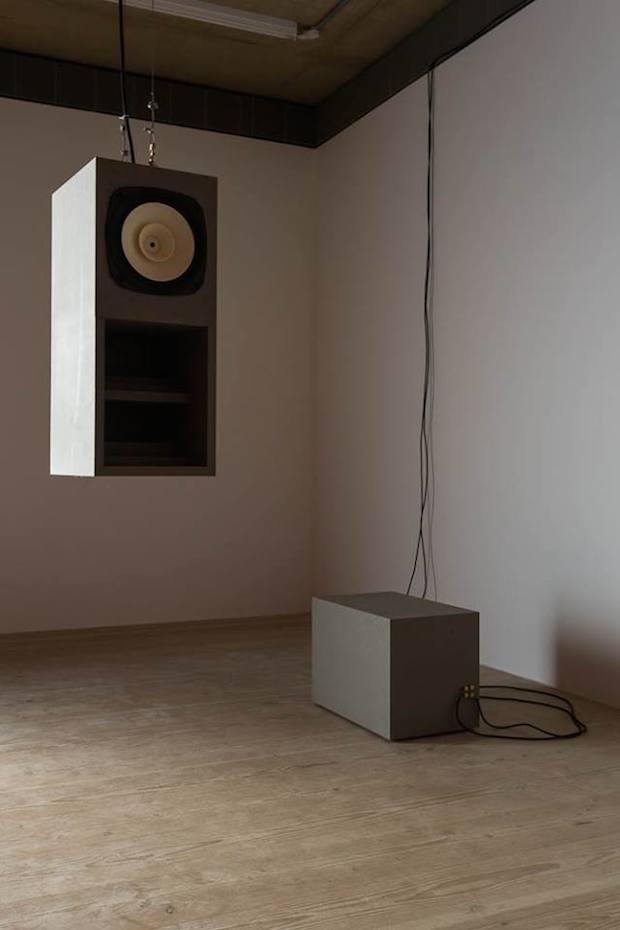

Sawtell, who has previously described her practice as investigating ‘the screen as a lens’, is fond of using dual images to create tension. This CGI animation is similarly unsettling in its movement. Whereas the glossy fluctuations of the oozing snowflake are presented to the reader straight on, in the other half the observer circumvents the cooling tower like a low-flying drone. The contrast between the two vantage points creates a disturbing sense of motion sickness, aided by the dark rumble of the piece’s sonic element. Sawtell, also an electronic musician and sound artist, has designed and installed a custom-made modular acoustic display for the exhibition, which works as an acoustic mirror to focus sound waves emitted from a series of audio transmitters into a central focus point. The result is a unsettling spacial element to the gallery: some areas feel heavier than others, depending on where the sound is concentrate. Sawtell’s engagement with the production of her show, including the craft of its display, is admirable and makes for a holistic installation rather than just an video piece.

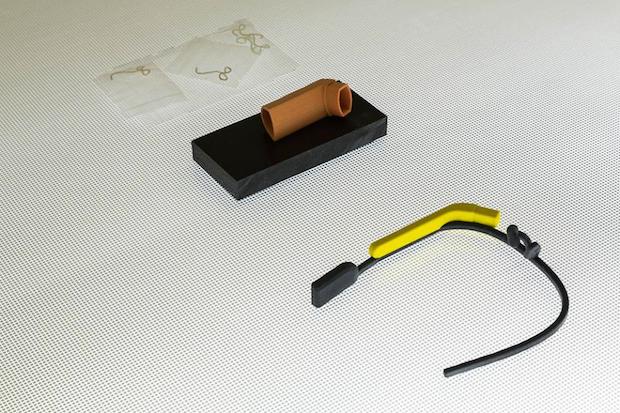

The same sort of attention to detail is visible in the presentation of Sawtell’s smaller sculptures in Focal Point’s Gallery 2. Eschewing formal plinths, these works sit on two bespoke tables made from a light box embossed with graph paper-like grids and supported with a powder-coated metal frame in neon yellow. The result is half examination table, half industrial work bench, and sets up the room for communal dissemination. For #STANDARDISER, Sawtell was keen to explore the idea of sculpture driven by data and so combed the internet for freely available, non-copyrighted wireframes which she could download to form the basis of her works. Ranging from the microbes of viruses like Ebola and Hepatitis C, to parts of a military drone, to a life-size model of the human heart, these digital patterns were then used to 3D-print and CNC-machine physical iterations. Intricate and often beautiful, these sculptures also show the variety and democracy of the internet, which allows the individual to self-manufacture something as innocuous as a replica human molar or as threatening as a military aircraft.

Elsewhere around the gallery, Sawtell has scattered smaller works. Focal Point’s large glass facade hosts colourful vinyls of the 1903-designed British Standard Kitemark, a now lesser used symbol of quality and British design and industry less. The piece #STANDARDISER_SQUATTER features the gallery’s display cabinets sealed up by a security firm usually hired to secure vacant buildings. Inside a huge quantity of Sawtell’s take on the unregulated and anonymously traded virtual currency Bitcoin have been stored. Two new issues of Sawtell’s free broadsheet series have been created especially for the exhibition. One depicts the routes of under-sea network cables across the globe, the other a visualisation of a solar-powered drone craft. There are a lot of different issues and ideas going on in this exhibition, and the audience aren’t force-fed explanations or meaning, and are instead encouraged to create their own connections between works beyond the obvious. It’s an exhibition that provokes questions rather than aiming to answer them (Is ownership relevant with regard to the internet? What is the potential of making resources, even dangerous ones, available to individuals? Should we police the web? Will humans ever tire or accumulation and consumption?) and a brave, uncompromising exhibition from such a small and newly opened gallery space.

#STANDARDISER

Focal Point Gallery, Southend-on-Sea

Until 20 December 2014

focalpoint.org.uk