Impressed by Ryan Gander's recent takeover of the modernist architect Ernő Goldfinger's home at 2 Willow Road, we probe this British artist's obsession with design.

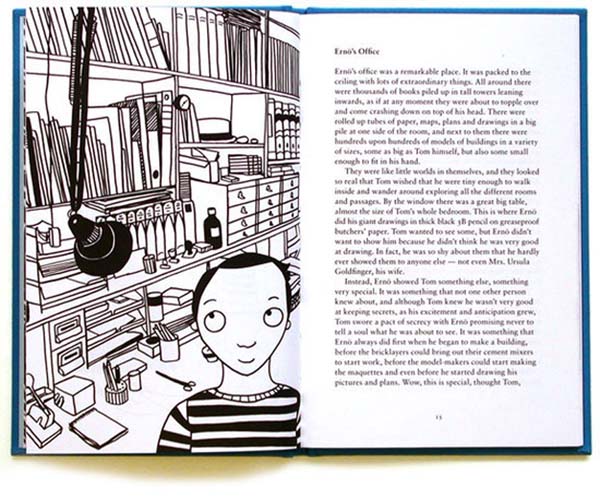

Tom, the protagonist of Ryan Gander’s children’s book The Boy Who Always Looked Up, first meets Ernö Goldfinger as he sits on his favourite perch, a wall opposite the big building site. From across the road a somehow equally big man catches Tom’s eye, breaks off his conversation with the suits and approaches: “Hello Tom. My name’s Ernö Goldfinger... Do you know why I’m here?” “Yes,” Tom mumbles, head tilted back, looking at the sky, “you’re from the council aren’t you?” “Kind of,” Goldfinger says, “actually, I’m the architect.” “The Archi-what?” cries Tom.

The Boy Who Always Looked Up

was written to accompany the installation An Incomplete History of Ideas, which won Cheshire-born artist Ryan Gander the Dutch Prix de Rome for sculpture in 2003. Though long out of print, in June this year Manchester’s Cornerhouse will reissue the publication with the additional support of Lisson Gallery, London. Few know Gander is the author of a book on the Hungarian-British modern architect Ernö Goldfinger. But then who really knows what Gander does? The artist’s industrious output avoids capture, is singularly, consciously undisciplined.

For Gander’s child protagonist the word “architect” is lumbering and unfamiliar, but swap their places and “Archi-what?” from the mouth of the artist is a cheerfully blithe provocation. Yet Gander’s work does not “trespass” into design to, as the artist Joe Scanlan memorably characterised the fad that is designart, provide “mood lighting and comfortable chairs” in a sham democratising of art institutions. For the most part it’s not even concerned, positively or negatively, with use value. In fact, in disciplinary terms, Gander does not ‘trespass’ anywhere; this is because his work is concerned less with the object, and more with the conceptual procedures that produce it. If his success proves anything, it is that being out of bounds in a world still demarcated by role and type allows privileged access to areas that even experts in their field struggle to reach.

Many of Gander’s artistic preoccupations appear in The Boy Who Always Looked Up: design, play, creativity, imagination, or what he recently called in his Paris exhibition Make every show like it’s your last (2013) at Le Plateaux, ‘imagineering’. An imagineering state — a portmanteau, in which the first part carries the sense of imagination, and the second a compound of engineering and mountaineering — is characterised by lateral, connective thinking. Imagineers recognise the propensity of things; their creative thinking is not inhibited by disciplinarity. Recently Gander told me how he is drawn to “designers who are pioneers and explorers.” So Goldfinger, then, we might assume, embodies the imagineering spirit. In fact there are a whole set of modern (and it should be said contemporary) imagineer-designers to which Gander is drawn, including Bruno Munari, Gerrit Rietveld, Charles and Ray Eames, and Le Corbusier, each of whom he has, in the past, made work in response to.

Among Gander’s greatest works are the various Rietveld Reconstructions (2005 – 2006), a series of sculptural compositions, made by children, using eighteen pieces of wood originally constructed as an Easy Chair from the Crate Furniture series by Gerrit Rietveld. Originally this ‘poor furniture’ could be produced cheaply with low-quality wood of the kind often used for packing crates (hence the name Krat). The crate chair’s formal simplicity, without joints or grooves, could be assembled quickly with a few screws. “Traditionally,” Gander writes:

"...we think of the modernist aesthetic as borne from ethics, or at least an explicit set of values, function above form, etc. So how does that translate into the idea of an artwork that exudes these values but is not necessarily produced under them?"

Would a child, presented with eighteen planks, channel the spirit of modernism and produce something resembling the crate chair? For the most part no, but the deviations from an archetypal form are fascinating. (At a gallery in Amsterdam a seven-year-old boy, Beer, managed to make the chair. “I began to hate him,” remembered Gander after Beer completed the build, “and his stupid chair... I began to wonder whether he had been tipped off, and who exactly had put him up to it”.)

The artist Alexander Calder frequently appears alongside Bruno Munari in Gander’s work. There is an ongoing debate about whether Calder, known for his kinetic mobiles, ‘stole’ the idea from the Italian designer and writer Bruno Munari. Gander’s take on this story is indicative:

"Munari made paper mobiles to be placed above kids’ beds and Calder made massive metal ones which were bought for millions of pounds. Essentially Calder copied Munari and everyone knew it. Munari was annoyed but he had so many ideas and projects that weren’t going for millions of pounds but were finding solutions to problems and being enjoyed. And being enjoyed. He just thought ‘fuck it’... Munari is amazing." ... ideas find their conceptually resonant vehicle; to be agile with language is to range freely across forms, mediums and materials. For Gander ideas are cheap; this is largely why his practice is so evasive. Ideas are scrapped, put on hold to be revisited, or actuated. In The Transdisciplinary Studio (2013) the critic Alex Coles seeks to theorise what he sees as a new kind of practice in which the studio is “a microorganism that actively generates objects across the contexts of art, design, architecture, and their respective discourses”. For Gander ideas find their conceptually resonant vehicle; to be agile with language is to range freely across forms, mediums and materials.

This is inimical to the received idea of a singular artistic practice, which Gander considers obsessiveness linked to the romantic image of the artist locked in the garret. This old fashioned idea is advanced by the marketplace and curators who, seeking authorial style or reliable thematics, encourage a kind of disciplining. (Anyway, Gander told me, who thinks in a disciplined way?) Both are just as likely to puff up micro-incremental advances in practice as significant departures. “Brilliant practitioners,” Gander believes:

"...are those who know how to move around language. If you move around language you have to move around devices and materials... When I’m making work one of the choices I make during a million other choices is what is it going to be? Why would a ‘really good practitioner’ use the same material for everything they do even though things are meant to mean different things?" Given his long-standing interest in modern design, you get the distinct feeling that this has been a dream project for Gander. As such art approaches what the American philosopher Daniel Dennett has called the “design stance”: an assumption of the predictability and purposiveness of objects. The design stance shares affinities with what the psychologist Wilma Koutstaal has called “functional fixity” — a cognitive limiting tendency of individuals to approach objects in the way they are traditionally used. That is, a restricted sense of the possibilities of objects due to abstract ideas of their function. Children — whose responses to art fascinate Gander — are generally less functionally fixed.

After its usual winter closure, 2 Willow Road, the Hampstead home Goldfinger designed for his family in 1937 — in the care of the National Trust since the mid-90s — reopened in March with an exhibition of new work by Gander. A total of fifteen works dating from the last couple of years, produced in response to Willow Road, are sited throughout the house, in the entrance hall, dining room, studio, living room, study and nursery. Given his long-standing interest in modern design, you get the distinct feeling that this has been a dream project for Gander.

Shortly after the publication of The Boy Who Always Looked Up Gander made a work called As Time Elapsed (2005) by stacking thirty copies on a floating shelf above head height. The colours and order of the books represented the interior of the communal spaces on each floor of Goldfinger’s Brutalist block of flats, Trellick Tower. At Willow Road The Boy Who Always Looked Up finds another form. In the living room a period television set clad in skeuomorphish wood grain — bought by Goldfinger to watch a television documentary about himself — shows documentation of actors performing the book as a dramatic radio play. In place of illustrations A flawed and wounded man bleeding frames onto a page (2014) supplements dialogue with foley sound effects created in the studio. Shot in one continuous take, the performers are apparently unaware of being filmed. Gander’s decision to show the visuals seems to undercut the illusionistic magic of foley studio sound. The disenchantment grates, but only perhaps serves to amplify the already anxious misplaced television set.

On the dining room table is Gander’s Henry Moor-ish sculpture The way things collide (Phaidon book, meets inner sole) (2012). Hewn, only partially finished, from a block of brown oak, it is substantial, heavy, hard and shiny: a flimsy inner shoe sole, less flimsy in oak, glances a coffee table tome. This is one recent manifestation of an on going series of the same title, which literally collides the least likely objects into a sculptural assemblage. Collision, the writer Arthur Koestler believed, is what characterises every new creative discovery or insight (designer Victor Papanek, an inspiration to Gander, learnt a great deal from Koestler). “The creative act,” he wrote in The Act of Creation, “consists in combining previously unrelated structures so that you get more out of the emergent whole than you put in.” Of course, Gander is himself the place where things collide most fortuitously — a model of how we all might throw off our functional fixities.New art by Ryan Gander is at 2 Willow Road until 2 November 2014

2 Willow Road, Hampstead, London NW3 1TH