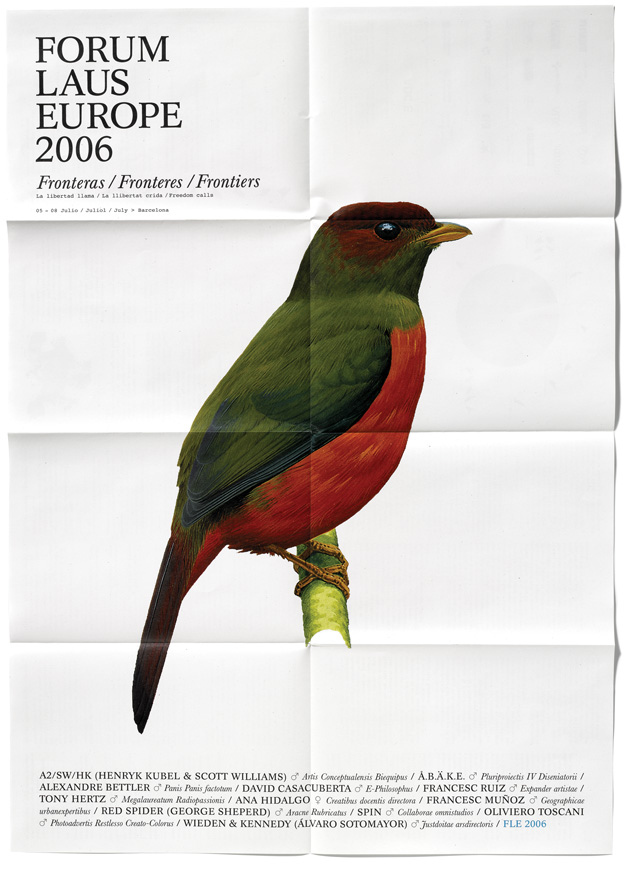

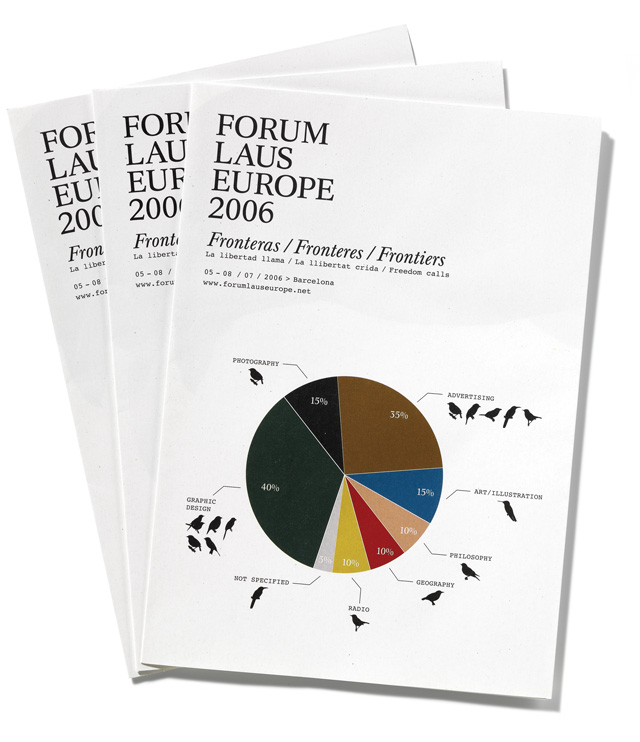

In this profile which first appeared in Grafik 180 in December 2009, Robert Urquhart went to meet Astrid Stavro in Barcelona – across the studio table, then over whiskeys, they discussed Spain, success and encroaching commercialsim.

I’ve been briefed by the wild-eyed taxi driver on the state of the nation. “There’s no industry apart from tourism, and that’s disappearing. People come here and they sleep on the beach because they don’t have the money for a hotel room.” He gesticulates using both hands to suggest the outline of a sleeping, poverty-stricken tourist. We swerve across three lanes of traffic and Barcelona comes close to losing another tourist in the process.

Barcelona is a beautiful labyrinth. Astrid Stavro made the city her home after finishing an MA at the Royal College of Art in London about five years ago. “I’d spent nine years living in London, most of my close friends had come and gone, I was living in a flat in Ladbroke Grove and it got to the point where I realised that if I died my rotting body would probably be found a month later,” she laughs. Time to leave.

Just prior to this frankly depressing self-assessment Stavro had achieved a major success with Art of the Grid, a project conceived by Stavro and her classmate Birgit Pfisterer as a final project and, more importantly, as a filler between leaving college and finding a job. “We knew that it was going to be hard after having the time of our lives at college,” Stavro recalls, “so we developed something that would keep us busy. Our tutors hated the fact that it was commercial, though. We thought it would probably sell to about three design freaks and that would be it—we were very surprised when we sold over 3,000 copies.”

Stavro arrived in Barcelona with thirty-five remaining copies of the Grid –It notepads and a contact at one of Spain’s main publishing houses, Planeta. “I suffered at first,” Stavro remembers. “A Carlos Ruiz Zafón book cover was returned ten times for corrections, and my attitude was ‘why can’t they find another designer and leave me alone? This is too commercial’. But then my contact said: ‘The Royal College is a bubble, I’m going to put your feet on the ground’ – and she did. It was a slap in the face, but then I needed it. I still work for them from time to time but we have both learnt what works for us.”

Wrestling with commerciality is something that Stavro seems to be constantly in turmoil over. There are countless times in the course of our interview when the conversation turns into a discussion about the commercial nature of a project – normally in reference to what Stavro perceives as work that is stylised and dull – but increasingly, especially when we move onto her latest work, it’s the nature of creativity, production and business that occupies us.

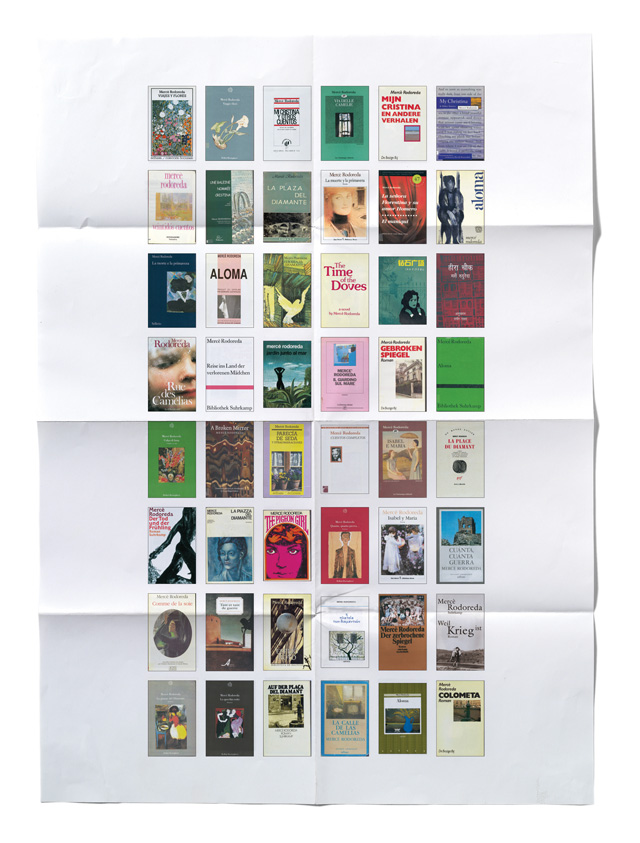

On her desk sits a stack of new projects – Stavro is in the process of launching an independent publishing company, Infolio Press. Books are a central core to her past design portfolio, yet as time has gone on she has adapted her role from ‘design stylist’ (“I hate that, when a client sees you merely as a service provider”) to that of editor and instigator.

One of the first books to be released under Infolio Press will be the continuation of a project by one of Stavro’s students, Axel Durana at IDEP, where she’s been teaching editorial design for the past year. The book could, and should, be a huge commercial success. The concept is simple. The working title is The Manual of Typographic Corrections. “Like my name, people get the spelling of Axel’s name wrong all the time,” says Stavro. “Axel started thinking about typographical errors and the systems we have for shorthand corrections and the signs we use to denote them. We’ve made a book of these and we’ve got the Robin Kinross of Spain, a guy called Josep María Pujol, to write the foreword.”

Between my visit to Stavro’s studio and writing up this article, Stavro gets back to me with an update on the book: “Instead of using a typeface that Axel has already designed, called Acsel, we are working on an Adobe plug-in so that correctors/proofreaders can correct manuscripts directly on-screen, directly on the PDF of the book, thus saving lots and lots of paper. It will work a bit like PopChar but this will be a direct plugin rather than external software.” Another commercial twist.

Back at Stavro’s stacked table in her studio, a couple of items stand out: a children’s colouring book and a box with some cardboard measuring tools inside. The colouring book is a reference to a discussion that is currently under way with Unicef for a twentieth-anniversary colouring book for children by Stavro-curated illustrators, highlighting Unicef’s laws. The measuring tools are a prototype for a product called Babyscale. “I was talking to someone the other day and they remarked that when creative people have children they invariably end up making work that has something to do with kids in some way. I guess this is mine,” she quips, “some kind of fucked-up creative shrine to my baby.”

Part of the inspiration for Babyscale came from a period a few months ago when Stavro’s two-year-old son, Marco, was in hospital. “I decided I wanted to open up some self-initiated projects. I was looking to get my mother involved in a business project and the idea of creating a product for grandmothers also appealed. Babyscale is a collapsible measuring stick to measure kids as they grow up. Instead of marking the frame of a door you can use the Babyscale and mark that.”

On the week prior to my visit Stavro had been to see Fernando Amat at his shop, Vinçón, on the Passeig de Gràcia near to her studio. This is the second time Stavro had visited the shop; the first was on her arrival in Barcelona. “When I first came to Barcelona I heard about this shop where every Tuesday afternoon the shop owner would see designers who had products to sell. I took the thirty-five copies the Grid – It notepads and went to see him. He liked it and put me in touch with Miquelrius which produces designer items, and together we made another run of the notebooks and he stocked them. When we were looking to develop Babyscale, Amat was the natural person to get in contact with. He said that I’d just completed the ‘easy’ part. The hard bit, the selling and distribution, started now, but he was interested, so that’s great.”

Amat seems to be something of a Simon Cowell figurehead for Barcelona’s aspiring designers. “Many people come and show me their products,” he tells me. “Usually I am only interested in analysing objects that are already in production. I find very difficult to judge projects—we take on ones we like and see if they work or not. If they sell, we continue stocking them; if not, we stop. Astrid's projects suit the kind of design-oriented customer that walks into my shop.” When I ask him about the current economic situation his reaction is rather bleak: “There is not much a designer can do to combat the recession. It all depends on manufacturers and to my regret most of them are not working on new projects right now.”

So Stavro is one step ahead of the game—her self-initiated projects do not solely rely on any one source of work or production, there are enough variables to keep her afloat. Aside from the publishing venture and product design work, Stavro’s traditional design practice is flourishing. A book collection for Arcadia and several book covers for Blacklist and Espasa are under way, as well as work for two exhibitions: Habitatge, which is touring the Lerida and Catalunya provinces; and Galeries d’Estudi at Barcelona’s new design museum (DHUB).

Stavro seems to be making the most of a design scene that is not only squeezed economically but also is not as large as the one that she came from in London. She’s ready to admit that much of the initial work came from word-of-mouth contacts that were keen to use her because she was ‘exotic’, having trained in another country and with a different outlook to homegrown designers. But then she is also ready to state that she sometimes finds Barcelona stifling and even backwards at times. “I find the marriage between the words ‘Barcelona’ and ‘design’ are a bit of an exaggeration. What is perhaps true is that there are several well-known designers and a handful of them happen to be here rather than in Madrid but it doesn’t mean that Barcelona is more of a hub than Madrid or Valencia. Barcelona as the ‘city of design’ was true a decade ago but the reality now, at least from a practising point of view, is that there are a lot of designers but very little good design and very few good designers.” Stavro is keen to put this in context, though: “Let’s not forget that for historic reasons graphic design is a very new discipline and that the recent recession has obliged many associations and institutions to cut back on design-related events and activities, to the point that apart from the recent opening of the DHUB there is little else on.”

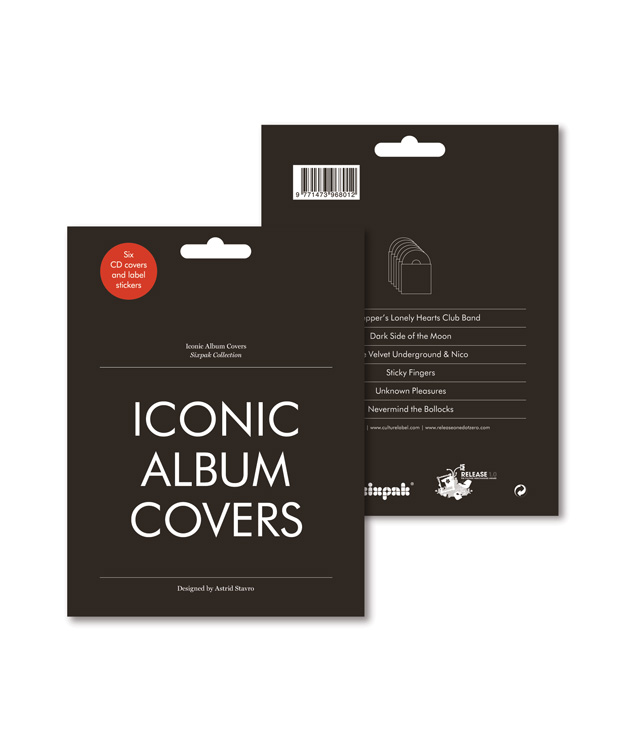

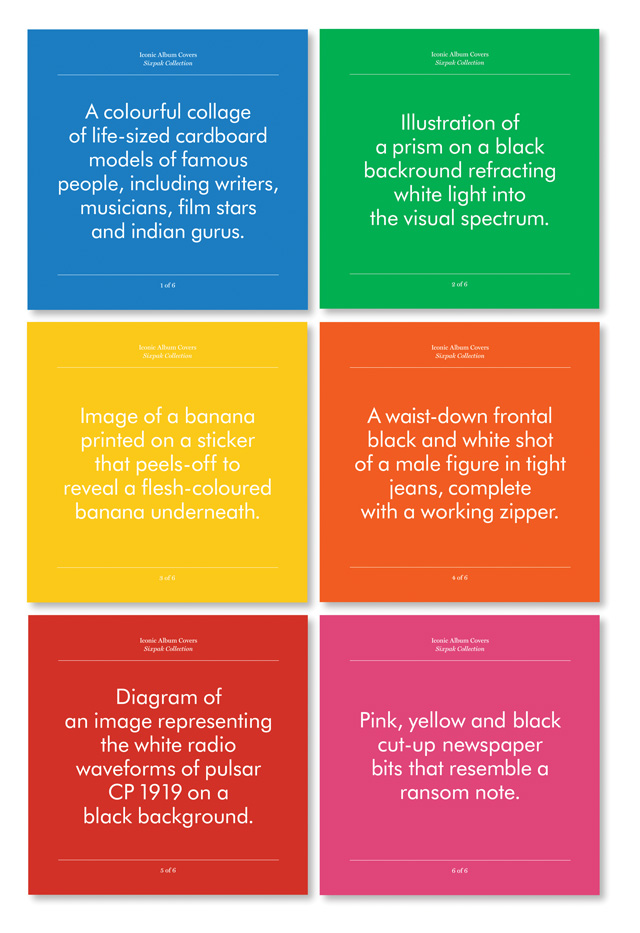

So why Barcelona? “The sea is around the corner, the zoo is ten minutes away, the food and wine—all the things that make life and this city so great.” Stavro has maintained her contacts in London too, and one of her most recent projects is a product for the ICA shop entitled Sixpak, a set of six CD and DVD sleeves.

“They initially suggested we did something along the Art of the Grid-It project but were open to suggestions so we developed a series of sleeves that typographically re-create iconic album covers,” she says of Sixpak. “These covers transcend their original context to become key cultural concepts, which insinuate themselves deeper into our shared, collective memory. We all know them; they come immediately to the mind’s eye when we recall them. The series is a cultural, historic homage as well as a fun trivia game.” The commercial legacy descending from Art of the Grid lives on.

Back in the more comfortable world of books, Stavro has major plans under way for 2010 as she shows me a book proposal for Laurence King called Graphic Design Icons, “a compilation of the world’s most iconic graphic design works selected by a distinguished group of fifty designer-curators from around the world”, and a plan for a conference in Barcelona in June called Rubrica: The Art of the Book. “It’s the kind of conference that I’d kill to go to, if I wasn’t organising it myself,” muses Stavro.

Later that evening Stavro and her affable partner, Pablo Martín, take me out for dinner and a few whiskeys at a local tapas bar. When the bill arrives I realise that I’ve not got enough to cover it—turns out my taste in whiskey has led to a couple of extra zeros added onto the end. Luckily Stavro and Martín gallantly step in and pay out. Yes, I’m testament to the fact that there are poverty-stricken tourists in Barcelona but, luckily for me, there are also enterprising residents who are using their entrepreneurial and creative talents to fight back. Astrid Stavro is a unique creative force and Barcelona is all the better for her choice of location.

View the original Profile article, first published in Grafik 180, 2009