Guy Bourdin went from Man Ray’s protégé to one of the century’s most conceptually daring fashion photographers – Somerset House’s autumn exhibition plans to reveal his gravitational effect.

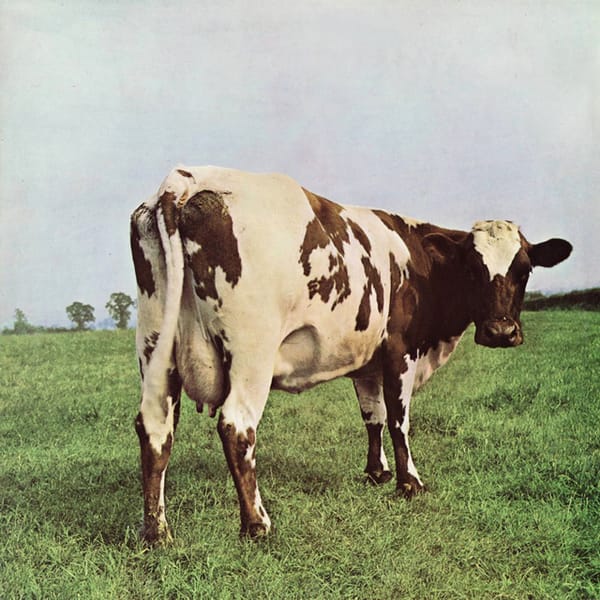

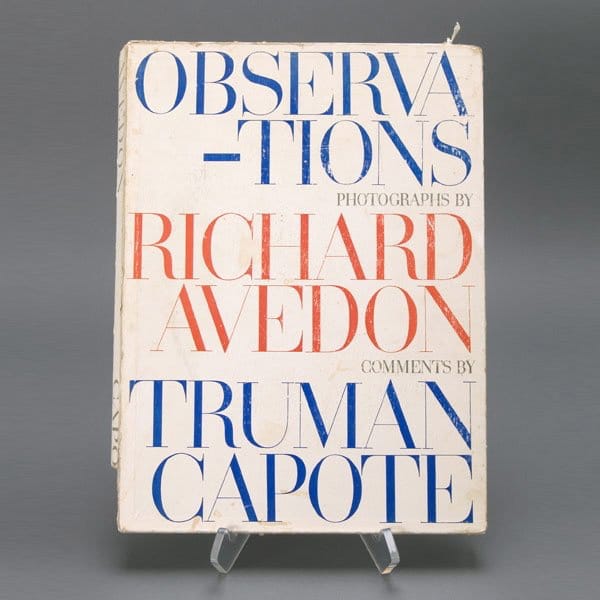

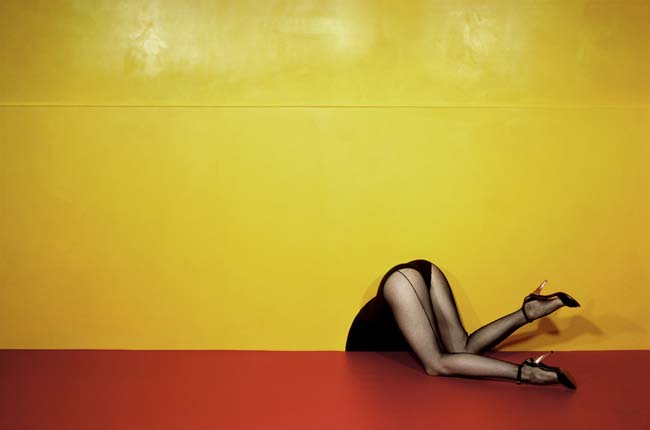

Though it is a phrase that is now so overused that it has lost all currency, as it pertains to Guy Bourdin, “pioneer” is label that retains all of its value. Credited with moving fashion photography into the realm of fine art, Bourdin’s images were often both overtly sexual and graphically violent, all coloured by a surrealism that was bestowed upon the photographer by his great mentor, Man Ray. Alongside this, however, Bourdin’s work had the sort of lush aestheticism and refined production that made it sit easily within the context of some of the world’s most respected fashion titles. He started working for Paris Vogue in 1955 and continued to do so until 1987. During his career his work would appear in almost every major outlet brave enough to accommodate his singular tastes: Italian and British Vogue were willing venues, as was Harper’s Bazaar; Issey Miyake and Pentax both commissioned calendars from him and Chanel, Bloomingdale’s and Gianfranco Ferre employed him to shoot ad campaigns.

A troubled and notoriously difficult man to know and work with – according to anecdote, models were reduced to tears and terror on a regular basis – Bourdin’s macabre style pushed into territory that bordered the pathological: rumours continue to circulate that one of his pictures is a recreation of his wife’s suicide and that he expressed an interest in using corpses in place of living subjects. This adds a darker reading to the photographer’s claim that his “pictures are just accidents. I am not a director, merely the agent of chance” – in actual fact, he would meticulously plan each composition with preparatory pencil sketches of the scene. He even took control over the hair and make up of his models and indicated to magazines exactly where each photograph should be placed on the page.

During his lifetime Bourdin published no books of his work, nor allowed it to be the basis for exhibitions. When the French government tried to bestow upon him the honour of the Grand Prix National de la Photographie, he summarily refused. Here was yet another example of an artist who, despite their virtuosity, or perhaps because of it, proclaimed a desire that their oeuvre be completely destroyed following their death. Contrary to this, however, his archive was latter discovered to be extensive and accessible, affording later generations the chance to view Bourdin’s images in situations he would have perhaps disallowed. This autumn, London’s Somerset House hosts one such opportunity, comprising an exhibition of over one-hundred colour prints, alongside less known black and white photographs from either end of his career. The show includes collateral materials such as Polaroid test shots, spread layouts and contact sheets and transparencies and even an array of Super-8 films shot on-location by the Frenchman; in all, it promises to be an exposition of his art and his process, as well as a venue to assess the significant and ongoing influence of a man whose motivations, passions and principles were far from benign.

Guy Bourdin: Image-Maker

Somerset House, London

27 November 2014 – 15 March, 2015

somersethouse.org.uk