Following the success of UK initiative Art Everywhere, a US version supersizes the project for the American landscape – critic Jessie Bond explores the idea of placing images in an unusual context.

My regular cycle home involves a steep climb along Latchmere Road from Battersea up onto Lavender Hill. At the top there is a set of traffic lights that provide a much-needed chance to catch my breath. A few weeks ago I stopped obligingly at a red light and glanced up at the digital billboard opposite: it was displaying a cloud sketch by Constable that serendipitously matched the light cirrus of the late August sky. For a moment I wondered at the aptness of this image’s location, before it was replaced by an advert for shampoo and the lights changed to green, forcing me to continue my journey.

This Constable sketch was on display as part of Art Everywhere, a scheme that returned to the UK this summer after its successful debut last year. From mid July to the end of August, twenty-five artworks selected through a public vote were displayed in 30,000 sites normally reserved for advertising. On static and electronic billboards, positioned along major roads, train station platforms, bus stops, and on the sides of buses themselves, images of artworks owned by the nation, have been on display across the country with the aim to “flood the streets with great British art.” Our hope is that this project will help encourage people to visit art galleries more than they do already. The project embodies an idealistic desire to share art with the masses by presenting it as non-elitist, perhaps reflecting the idea that art is good for you, that there is something improving or bettering in looking at a work of art. Or, it could be seen simply as putting artworks to use to improve the urban environment with images that are not trying to sell something. Grayson Perry remarked when launching the project that the streets are already full of street art, why not place ‘gallery art’ on the streets too. Art Everywhere’s director Stephen Deuchar states that: “Our hope is that this project will help encourage people to visit art galleries more than they do already.”

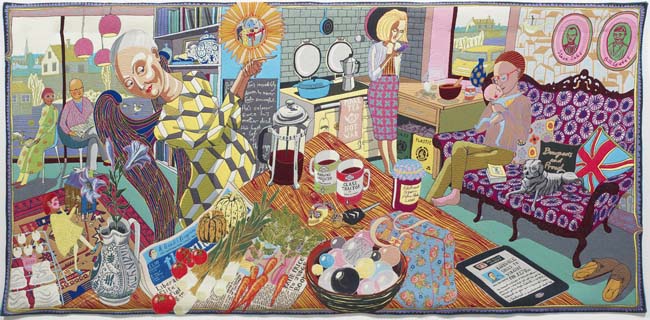

Although long-listed by curators, the final artworks were chosen through a vote on Facebook. Unsurprisingly, as with most popular votes, this year’s selection was formed of favourites old and new such as Perry’s recent tapestry The Annunciation of the Virgin Deal (2012), Marc Quinn’s infamous self-portrait cast in blood and historic works such as The Ditchley Portrait of Elizabeth I.

The scheme was premiered in America this summer. There, five institutions collectively nominated one hundred artworks, before a public vote shortlisted the works that were shown on 50,000 sites across all 50 states. Realised with the support and cooperation of the advertising companies and the public art institutions that own the artworks, understandably, Art Everywhere describes itself as the largest outdoor exhibition ever conceived.

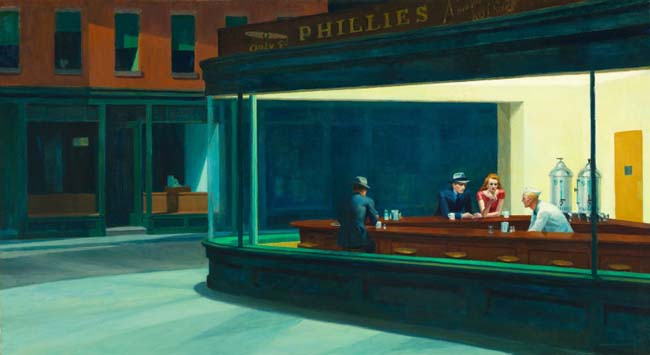

Out of the artists that made the final fifty eight in America, Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks (1942) was the most popular. This iconic, voyeuristic image of the inhabitants of a downtown late-night diner is one that US citizens most identify with. The list also included images of national pride such as Gilbert Stuart’s portrait of George Washington, and examples of the pop art movement – Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Can (1964) and Roy Lichtenstein’s Look Mickey (1961) and Cold Shoulder (1963) – that perhaps are most often identified with American art. Although it seems perhaps slightly ironic that these works, which once were a critique of consumer culture, are now being shown on billboards, one of the most invasive forms of advertising in public space.

Particularly in America driving is a part of everyday life for a large portion of the population. Billboards line major roads, cluster on the edge of cities, and the adverts they carry are designed to be seen from a distance or fast moving traffic. Their slogans and bright colours are made to grab attention, designed in some way to stick in the mind or instantly impart their message. Especially in an urban environment, where these adverts appear in high density, how can artworks be expected to compete and not just get lost in the visual noise?

Despite the risk of going un-noticed, the potential to reach a wide, uninitiated audience, evidently gives the billboard or poster a strong appeal, and Art Everywhere is not the first major public project to utilise such sites. Since 2000, Art on the Underground has worked with contemporary artists – who may not be so well known to the general public – to present works that infiltrate the lives of London’s commuters. Whilst they also use various parts of the underground, such as covers of tube maps and whole stations, many of these commissions are visually present as posters, such as Jeremy Deller’s What is the city but the people? (2009). Deller produced a pamphlet of quotes to be read out by drivers on the Piccadilly line, which was accompanied by a series of posters with some of these quotes from well-known figures such as Ghandi and Goethe.

In New York in 2009 High Line Art was established alongside the opening of the High Line – a public park that inhabits a historic freight rail line elevated above the streets on Manhattan’s West Side. Part of this scheme is a billboard commission, where for roughly a month at a time, a contemporary artwork is displayed on a billboard next to the High Line. So far artists such as Elad Lassry, Gilbert and George, and Thomas Demand have taken on the commission. In 2011 John Baldessari used the opportunity to produce a giant $100,000 bill, entitled The First $100,000 I Ever Made. The work made a great photo opportunity for those visiting the park or passing by, as well as a wry comment on the potentially opposing forces at work between advertising, art and consumerism. In being displayed alongside adverts, these artworks become purely image... Unlike these commissions, which display works made for specific sites, Art Everywhere offers an encounter with an image of an artwork, rather than the original. And this encounter might only be a glimpse of the image, before the billboard rotates or the traffic moves on or the train speeds through the station. Within the gallery context longer, considered engaged looking is encouraged. Institutions, responsible not only for the conservation of the material of an artwork but also its context and interpretation, supply the viewer with additional information. In being displayed alongside adverts, these artworks become purely image, which could perhaps be seen as problematic.

There is potentially an uneasy relationship between advertising in public space and art works. Last year the proposed poster for Catalyst, an exhibition of contemporary artworks made in response to conflict at the Imperial War Museum North in Manchester, featured Photo Op (2005) a photomontage by Peter Kennard and Cat Phillipps that shows Tony Blair taking a selfie in front of a burning oilfield in Iraq. Two major advertising companies, JCDecaux and CBS Outdoor, refused to carry the poster on the grounds that it potentially breached the advertising code of conduct. Although they were not more specific, the code includes rules forbidding ads that are misleading and likely to cause “serious or widespread offence”.

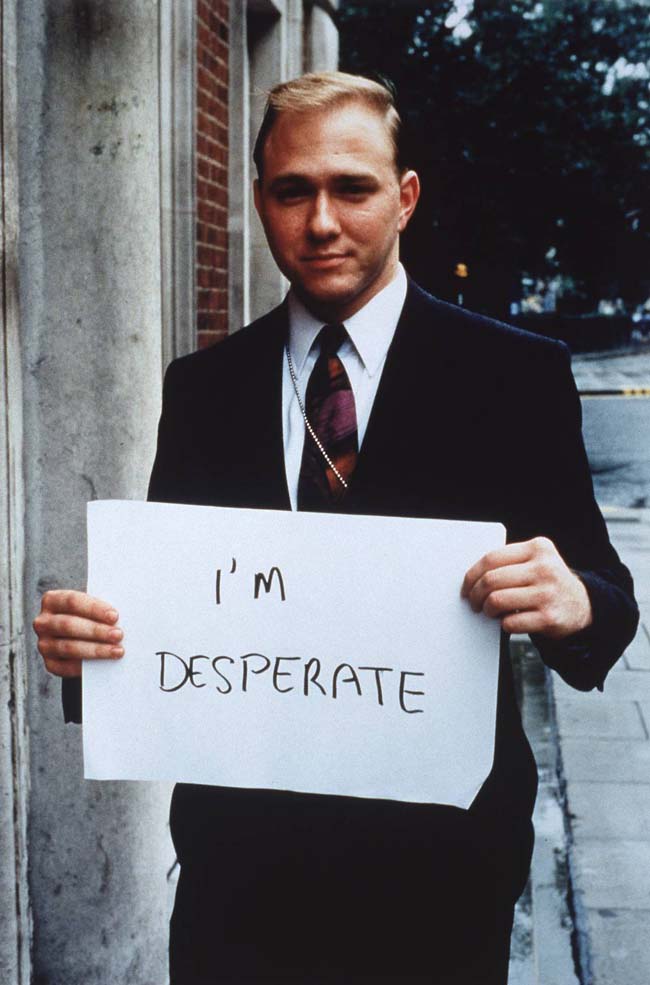

Advertising companies have also been accused of borrowing from artists without fair acknowledgement. Gillian Wearing accused both Levi’s and VW of copying her work Signs that say what you want them to say and not Signs that say what someone else wants you to say (1992-1993). To create this work Wearing approached 600 members of the public on the streets, asking them to write something on a piece of A4 paper before photographing them. One of this series, featured in Art Everywhere this year, captures a businessman stood on the street holding up a white piece of paper on which he has written, “I’m Desperate”. Here the image of the artwork...becomes a background for countless selfies. It seems hard to judge the success or failure of Art Everywhere, how to gauge if these billboards have been noticed or what their impact may be. Unless you travelled widely throughout August, taking different routes each day, you are most likely to have encountered the full range and breadth of Art Everywhere through social media. The project actively encouraged engagement through Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest and Facebook, and it seems this is where evidence of success can be found. Here the image of the artwork is re-photographed, re-contextualised, re-circulated, and becomes a background for countless selfies. Whilst there is an evident joy in finding these works in unexpected public locations, I wonder if cutting out the middle-man and directly placing these artworks in online marketing positions, would result in them encountering more passing traffic. My day would be much improved by the appearance of Constable’s cloud sketch instead of the cookie-driven ads that litter Facebook, Twitter and my inbox.

jessiebond.co.uk