Exposing the Eastern European avant-gardes in sound and image after Stalin’s death — David Crowley talks us through this wonderfully esoteric show.

Peter Maxwell: The exhibition title is arresting and enigmatic, why did you choose it?

David Crowley:

It’s a direct reference to Walt Whitman’s “I sing the body electric” (I SING the Body electric; […] Was it doubted that those who corrupt their own bodies conceal themselves;”). We were interested in the idea that this engagement between experimental art and music had implications for what a body might be: in the context of Eastern Europe in the 50s and 60s when you think about bodies being battered by war, by Stalinism, and then the idea of the liberated body, the body that’s able to generate sound, or the body that is able to move through space, it has this euphoric set of associations. If you come to the show you see that some of the musical environments set up by theses avant-garde artists are as much about liberating the body as they are about the creation of new kinds of music.

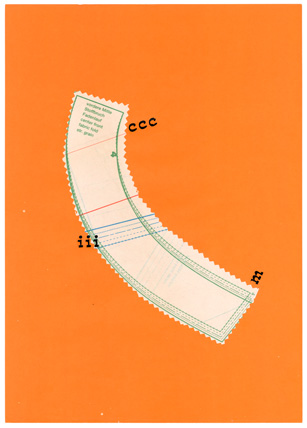

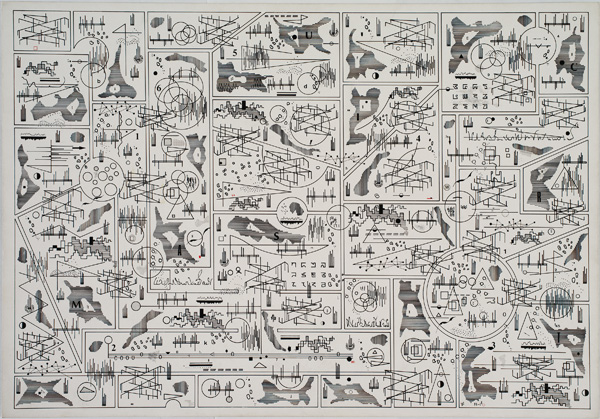

PM: There are some fascinating examples of graphic notation included in the show – it feels like a topic that has been ably dealt with by the histories of both contemporary music and art, but in terms of graphic design has been somewhat ignored?

DC:

Absolutely. There’s a whole history of expressive graphic marks that graphic designers ought to pay attention to. In the show we have two types of graphic scores – we have scores that are really designed to release improvisation, so a figure like Bogustaw Schaeffer will design a language that he would suggest allows for great varieties of performance. The musician who is presented with one of his scores is given a certain kind of freedom. That’s important in an Eastern European context, the idea that a score is not an instruction but an invitation to improvise; if you think about living in a culture that is dominated by command and power structures, dictated by the Kremlin, the idea that you can improvise is somehow a political message too. The second kind has to do with early forms of electronic music, or musique concrete – the first piece of music we have in the show is called Study on a Single Stroke of a Cymbal by Wlodzimierz Kotonski, who took that sound and processed it in various ways using oscillators and primitive synthesizers so you have this full, almost orchestral range. In order for it to qualify as a piece of music it had to have a score, even though it had in not been written in the classic sense. How do you describe the extraordinary vibrating tense sounds of the cymbal? What should these sounds look like as a piece of musical notation? Here’s a composer that had to invent a graphic language to capture a new musical form.

PM:

Why was the relationship between visual art and experimental music so close in that particular time and place?

DC:

It seems to me that there are times in history where the visual arts and experimental music come quite close, you can imagine them as two tracks of history that are occasionally in close proximity and then pull apart. Take the period just before the First World War, for instance, you see lots of experiments connected to ideas around synesthesia. The composer Alexander Scriabin is a good example, with his close relationship to Symbolism and to colour theory. In the moment that I’m interested in, in the 60s, artists and musicians across the world are either working together or else refusing those as separate categories. If you think about Fluxus, while it was an experiment in the visual arts it was also driven by a lot interest in music. Presently it seems to me that there is a lot of discussion of ‘sound art’, though it’s not a term I like, but it’s certainly in the air. There is a meandering relationship between these two things that came together particularlystrongly in Eastern Europe.

PM: How much emphasis should be placed on this West to East direction of influence, the impact of Fluxus and figures like John Cage? I get the impression that the show wants to make a statement against that movement of travel?

DC:

A lot of people are very interested in the relationship of Cage to the show, and we know that some of the artists that we are showing had an interest in Cage. Indeed he did come to Warsaw and Prague in 1964 and then periodically went back to Eastern Europe, but I don’t want to overplay that because it starts to produce a framework where you can only understand it by seeing it through a Western eye. We’ve focused exclusively on Eastern European artists precisely because we want to explore their particular relationships and the currency of the ideas in their world. To only see it through a Western lens is to relativize it in a way that does a disservice to those artists. But you have to remember that Fluxus set up by George Maciunas, a Lithuanian artist, who even offered Fluxus to Khrushchev in the early 60s saying “we will be the artistic wing of the Thaw”, of the new politics of Eastern Europe; Fluxus was East-West right from the beginning.

PM: Was that a desire from the outset, to perform some sort historical surgery, to re-balance the perception of the conditions of this particular art historical moment?

DC:

A lot of my work has been about trying to create a more complex picture of Eastern Europe. If you ask most people in London to imagine Warsaw in 1963, they’ll likely have images of heroic workers and socialist realism. What I’m trying to show is the vibrancy of the Modernist experimental artistic culture that was really animated in that time.

Sounding The Body Electric: Experiments in Art and Music in Eastern Europe 1957–1984 runs from 26t June – 25t August. A CD of recordings of works in the show will be issued by Bólt RecordsCalvert 22, London 26 June to 25 August 2013