James Turrell makes graphic 3D sculptures by harnessing light to mind-blowing effect. In this ode to the American artist, Hush partner David Schwarz explores how Turrell’s later pieces work as a metaphor for an ideal to which all designers should strive.

As a designer, my primary references are artistic but my primary output is commercial design. This is because I believe design referencing design is a snake eating its own tail. It overlooks the intangible power of untethered artistic expression, which while sometimes nonsensical and irrational, has a unique hold on the human spirit. Of course, as a design student, I spent countless hours hypnotised by the interdisciplinary design references of Glaser and Müller-Brockmann, Kubrick and Goddard, Kahn and Le Corbusier. But insight from the art world is different. It reminds me that there is undeniable purity in some forms — often unexplainable, but powerful nonetheless.

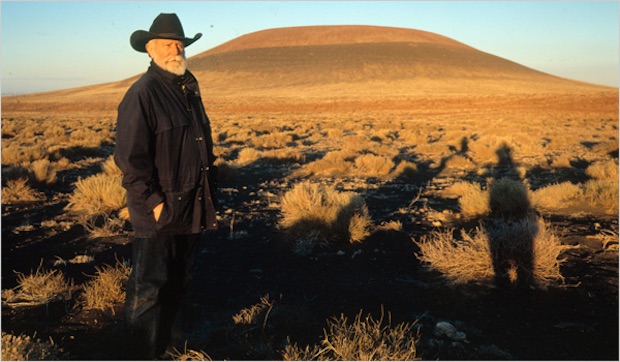

Enter James Turrell. The man with the white beard and bolo tie is an artist, not a designer. But in lieu of wasting precious words arguing the difference between the two, the distinction falls away when looking at the shared values across these practices and how they’ve inspired me personally and our design agency: minimalism, truth, rigour and meditation.

While I certainly wasn’t the first person to obsess over Turrell, I’m not a newcomer either. The scale and breadth of his recent shows (at LACMA in 2014, Guggenheim New York in 2013 and MFA Houston in 2013) has permeated the zeitgeist, touched a mainstream audience, and has made him an (artsy) household name. But before that, I was hooked on him early in my career when I first read of his works from the mid-Sixties created at the Mendota Hotel in Los Angeles, called the Mendota Stoppages. Holed up inside, he took over multiple rooms, and, after blocking out all external light, systematically cut holes in the exterior walls. This allowed only small, controlled beams of ever-changing sunlight into the space. Imagine that: he was so obsessed with the understanding of this exterior medium – light – that he needed to go to the interior to explore it. He could, unlike everyone else in Southern California, consciously remove himself from the grandeur of the California sky in the pursuit of his internal mission – a much darker place, a cave, punctuated only by the graphic shapes of white light hitting the contours of architectural interior. To me this is pure obsession. This is an unwavering, dream-like trance: a meditation on light.

I do not possess this same depth of fixation - but it does inspire me deeply. I’m in awe at the purity of what Turrell was chasing, and continues to chase. In that bare hotel, the raw material of his work was photons, translated from an all-encompassing glow originating 93 million miles away but finally given shape by Turrell’s own hand. What a metaphor for the design of anything; to take the rawest of raw materials and shape it with the most minimal gesture.

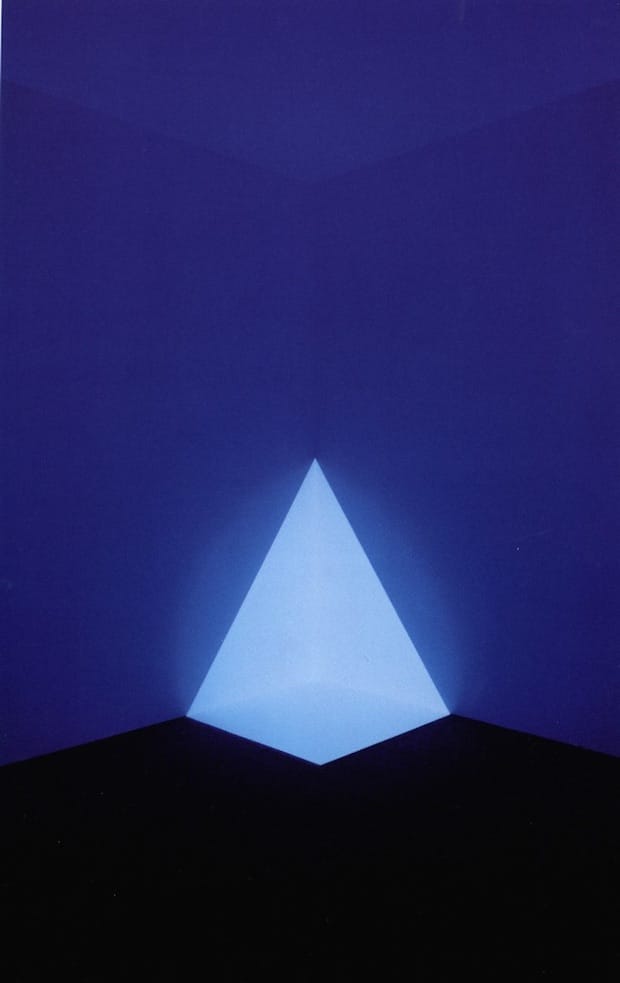

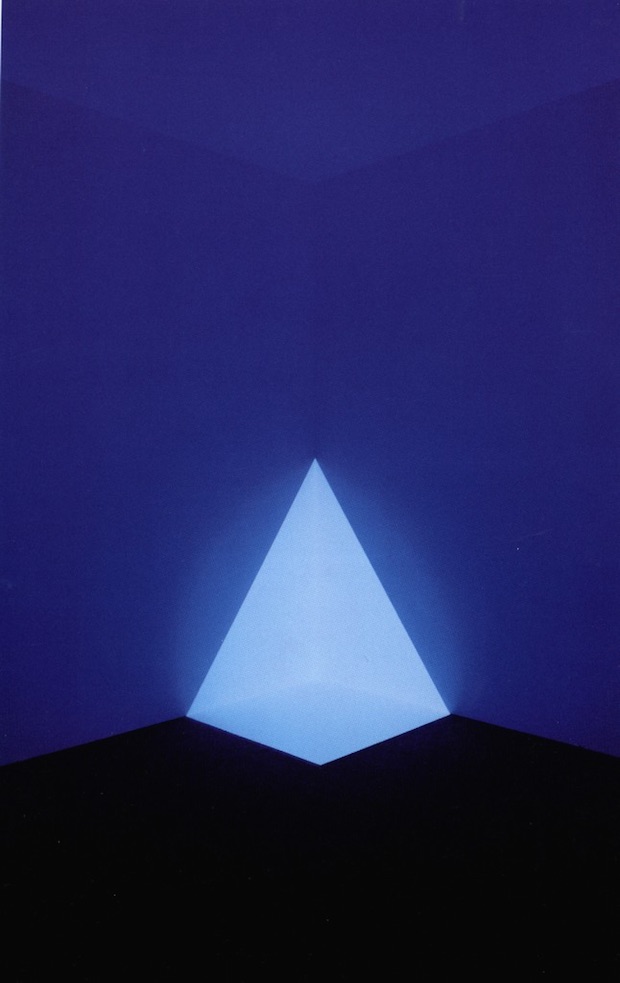

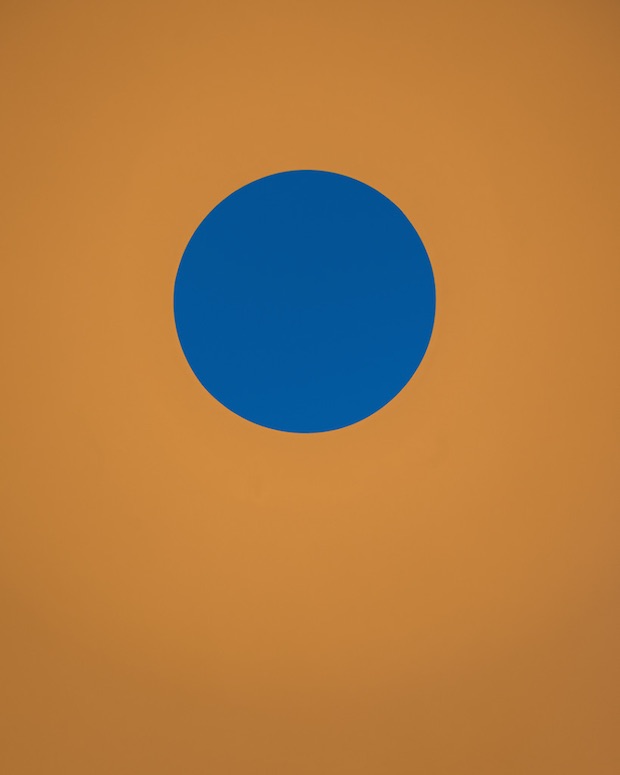

I love this man who has meditated for decades on the simplicity of forms of the circle, square and triangle, the line, the arc and the ellipse. And if that’s not enough, he has been able to perceive the subtle differences in those light-driven shapes as the tonality, texture, angle and temperature of that illusive light changes over infinite cycles of day and night. He has done with light what Sol Lewitt has done with graphic shapes. He’s rigorously manipulated the seemingly uncontrollable into the simplest of forms, and wrestled the infinite into the finite.

While Turrell has studied and produced work across an enormous range of light sources, from natural sunlight to fabricated, electrical light, in a spectrum of fantastical colours and blended hues, I’m most obsessed by the work he created very early and very late in his career.

At one end are the confines of that LA hotel. On the other, the great Western expanse of an Arizona volcanic crater called Roden, a project that began production in 1979 and continues to this day. It uses the cone of the volcano as a natural oculus, and through a series of fabricated tunnels and interior chambers, he’s aligned Earth-bound architecture with the sun’s daily path across the desert sky.

Can you conceive of another artist who has taken on such a broad medium and controlled it across such divergent scales, from the footprint of a single hotel room, to that of a vast desert landscape? What kind of man-god has this power of control? Or stamina? Or rigorous inquisition? Or patience?

Imagine also, to engage in a practice of artistry so ephemeral that it can’t be practiced after the sun sets. Imagine a design process that chases the sun. His own critique, adjustment and refinement play out in his memory during the dark hours, only to be recalibrated in real-time when the light returns. Between sunrise and sunset, he sees the fruits of his labour, timed to the unique, but ever-repeating, position of the seasonal sun.

In the context of the commercial design field, we cannot find a better inspiration for the purity of form, graphic perfection, and transcendental response. I can’t count the amount of times we’ve used his work as a reference to convey the power of simplicity and the ability for so little to do so much. The irony, of course, is that an image of his work in a reference deck does so little for the viewer when compared to the visceral response the work engenders in person. Time stops, eyes dilate and you become aware of your own body, its systems and processes, and slowly give into the void as figure becomes ground. This economy of visual structure is at the core of what we should do as designers. If we can bring even a fraction of his magic to our world of design, we find success.

I’ve never met Turrell in person. I have a friend that knows his friend. I know an architect who redesigned his kitchen in New York City. Everything I know is through hearsay, academic research, or the first person account of his exhibited work. I don’t know if he’s pleasant or mean, extroverted or contained, philanthropic or self-involved, but it doesn’t matter. I regard him with a mythic warmth that I can’t explain, as if the decades of light have somehow filled him up and now radiate outwards towards anyone who can see it. James, if you’re listening, put me in that crater.

heyhush.com