The vastness of Russia makes it a country effectively unknowable, a challenge that, as Calvert 22's current exhibition elucidates, native artists have frequently defined themselves against.

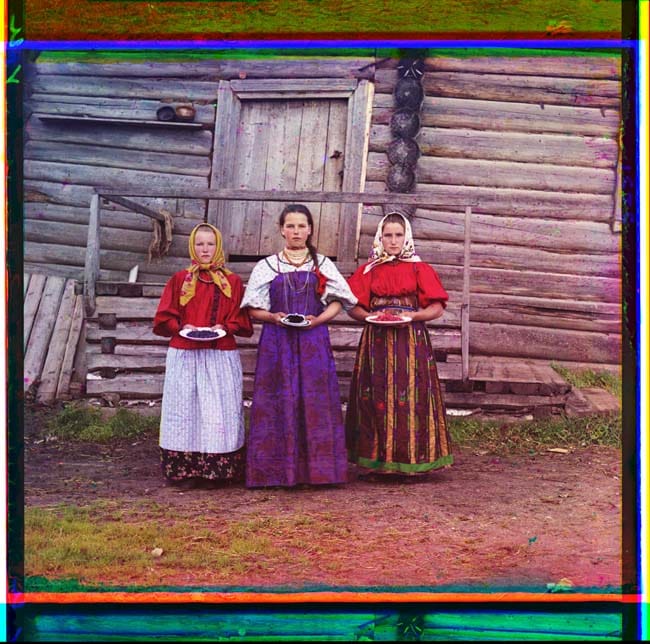

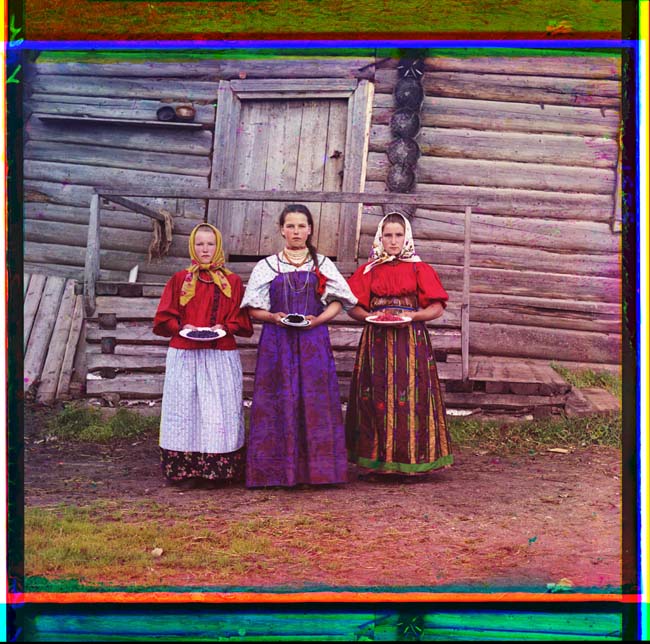

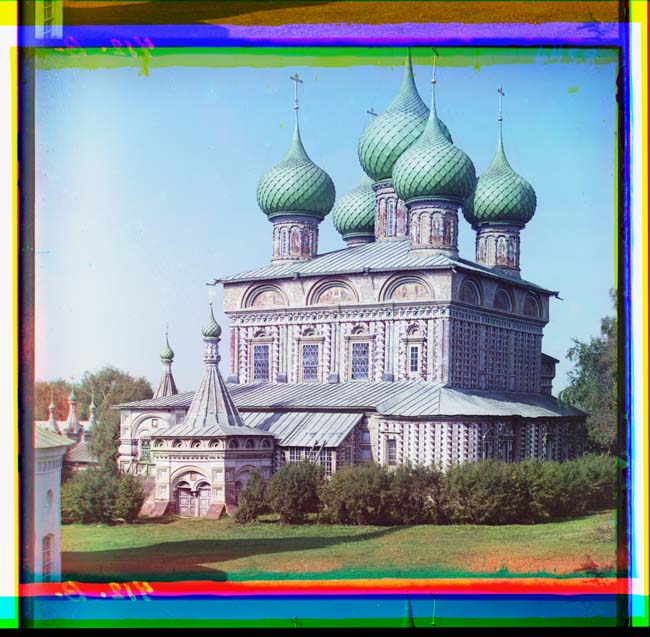

Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky was a pioneer of ‘colour separation’ or ‘three colour photography,’ a technique that allowed full colour photographs to be captured on glass plate negatives and subsequently projected. Nicholas II, the last Tsar, was keen to see his empire documented and celebrated through this innovative technique and commissioned many of the photographs that currently form the core of an exhibition at London’s Calvert 22, Close and Far: Russian Photography Now. These captivating images, taken of Russia’s vast empire between 1905 and 1915, provide a historic context for the work of five contemporary artists whose own photographs and video reveal an enduring relationship between the Russian population and the natural environment.

In 1909 Prokudin-Gorsky was granted the permission and funds to travel continuously for six years in a specially adapted railway carriage featuring a darkroom. He was given unique access to diverse locations such as the plains of the Mariinsky Canal and river system, the newly industrialised landscape of the Ural Mountains and the Samarkand area of central Asia. In documenting the people, architecture, agricultural techniques and new transport systems of these unique regions Prokudin-Gorskywas not only satisfying the demands of the Tsar, but also his own desire to create a thorough ethnographic study of his country.

The prints created for this exhibition seem anachronistic; not only are the places depicted unfamiliar but this multicoloured view of the early twentieth century is also deeply foreign. The photographs appear more aesthetically akin to images from the 1960s, an era in which technological advances allowed colour photography to become commercially viable. Yet Prokudin-Gorsky’s use of photography is very much of his time, in that it shows a fascination and faith in this relatively newfound ability to mechanically reproduce the appearance of the world. In some ways these images were a political tool, celebrating both the heritage of the empire and its burgeoning modernisation. But for Prokudin-Gorsky, photography also offered a way to understand the world through its appearance, and to educate young people about places they may never otherwise see.

It’s somewhat fitting then that Prokudin-Gorsky’s photographs are displayed here alongside the work of a new generation of photographers. These images, created over a century apart, are united by an impulse to expose traces of the past within the Russian landscape and document the continuing importance of rural traditions.

Alexander Gronsky’s series Pastoral focuses on the suburbs of Moscow, showing the city’s inhabitants seeking rural pursuits within incongruous, bleak settings. Mar’ino III (2010) depicts a small group sat beneath leafless trees, ostensibly picnicking on a litter-strewn riverbank, whilst in Dzerzhinskiy II (2009), families and couples relax, sunbathing on or sliding down piles of waste sand. Many of his photographs feature rows of Soviet tower blocks looming in the background.

Like many of the photographs in the exhibition, although the locations may be unfamiliar, their formal treatment is situated in the recognisable territory of recent Western photography. Pastoral brings to mind Mark Power’s photographs taken in Poland, whilst Reconstructions – a series of triptychs also by Gronsky – initially appear reminiscent of Jeff Wall’s staged photographs. On closer inspection it becomes apparent they are in fact more candid, documenting the unfolding of public historic re-enactments. The neat curation of the exhibition places these triptychs in proximity to Prokudin-Gorsky’s photographs relating to conflict, such as one taken in 1915 documenting Austrian prisoners of war in front of a barracks near Kiappeselga. This thematic echo reveals the simultaneous role of photography as witness to both the events of war and the rituals of its remembrance.

Reverberations from the past are also present in Olya Ivanova’s portraits taken in the town of Kich Gorodok and the surrounding depopulated villages. In creating these images Ivanova took a visual lead from the archival family photographs of her subjects. A digital slideshow of these formal black and white images celebrating marriages, births, christenings and anniversaries are displayed here. Ivanova’s portraits are haunted by a sense of occasion, bearing an uncanny resemblance to Prokudin-Gorsky’s photographs. In 1909 three peasant girls in finest attire, holding plates of food, compliantly pose for the camera in front of a wooden building; in 2010 a girl in her best dress poses seriously in front of a near identical structure, clutching a plastic bucket. In addition to this seeming collapse of a century, these photographs reveal a more recent lineage: Ivanova’s tender treatment of her subject matter is reminiscent of Rineke Dijkstra’s portraits of young girls posing, vulnerable and awkward on the beach.

Whilst Ivanova’s photography is influenced by tradition, Max Sher’s series Russian Palimpsest (2010 – ongoing) creates an image of Russia that has been neglected, even prohibited. Sher explains that whilst romanticised or politicised imagery is one often associated with Russia, this more anonymous, more everyday vision has been omitted, perhaps due to the fact that during the soviet era, street photography was considered tantamount to spying. To rectify this he aims to document forty cities across Russia in a dispassionate and methodical fashion.

Some of the resulting photographs are startlingly similar to photographs from Stephen Shore’s iconic Uncommon Places: we see street intersections, near-empty? parking lots and telephone wires dissecting the sky. In others the banal facades of new commercial buildings are more reminiscent of Lewis Baltz’s documentation of industrial parks; yet this is not suburban1970s America but contemporary Russia. Sher’s photographs are titled with the place and date when they were taken, along with their precise geographic coordinates. He states that this is an acknowledgement of the interconnectedness of the landscape with online mapping systems now widely available; seemingly he is influenced as much by Google Street View as New Topographics.

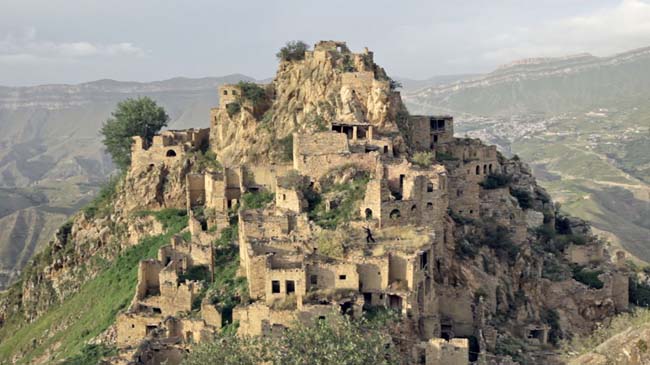

Two video works projected in the basement compliment the photographs displayed on the ground floor. These too explore the bond between man and nature, and the rituals that have evolved around this exchange. Taus Makhacheva’s Gamsutl (2012) features a figure clad in black, pulling a series of poses amongst mountaintop ruins. From a similar elevation to the performance, the camera captures the movements through a series of different angles, yet the precise meaning of the poses is hard to decipher from this distance. The gestures at first appear reminiscent of Tai Chi, but are in fact borrowed from nineteenth-century battle scene panoramas painted by Franz Roubaud and the diagrams of soviet-era agricultural instruction manuals.

In contrast Dimitri Venkov’s Mad Mimes (2012) takes a lighter, satirical stance on tradition, rituals and the importance of the landscape in Russian consciousness. Venkov’s pseudo documentary follows a tribal group living next to the Moscow Ring Road, surviving from the detritus that the road generates. We see them carry out a series of ceremonial acts evoking the dissonance between this road – symbolic of rampant modernisation of the city – and an agricultural past. Similarly to Gronsky’s images of historic reconstructions, acting-out becomes a way to process past events, locating them within the present in order to come to terms with their consequences.

The works that form Close and Far: Russian Photography Now disclose a fresh image of Russia, captured both prior to the revolution and in the decades after the collapse of the Soviet Union. Photography, in its ability to record and repeat, acts as a link between multiple pasts – both real and imagined – and the future.Close and Far: Russian Photography Now

Calvert 22, London

18 June – 17 August 2014

calvert22.org