Deliciously ambiguous and full of filmic qualities, the work of Swedish artist Gunnar Smolianski deserves to be better known in the UK, says Jessie Bond.

Born in 1933 in Visby, Sweden, Gunner Smoliansky has been taking photographs since the 1950s, working first as an industrial photographer and then freelance creating images for publishers of textbooks. Throughout this time he was also photographing autonomously and in 1971 had his first solo show. Since then his reputation had grown in Sweden yet surprisingly he still remains little known in the UK. A show last year at Michael Hoppen Gallery was a rare, welcome outing for Smoilanski in London. At that show, the black and white photographs, predominantly taken in Sweden, demonstrated Smoliansky’s adept handling of the medium, which he utilises to convey a deep curiosity with the everyday alongside forging a subtle distortion of reality.

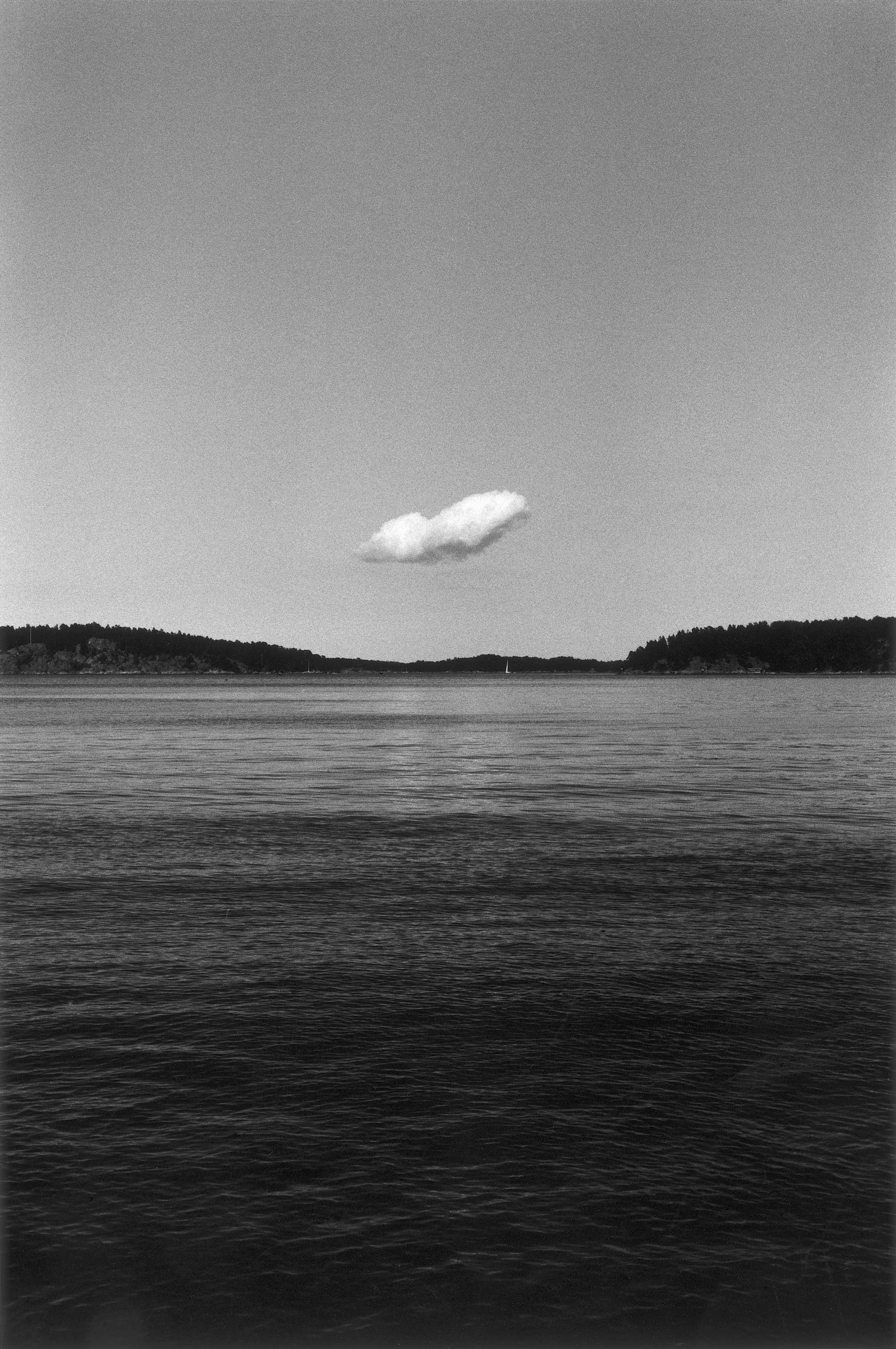

Although located in a European tradition of documentary photography, Smolianky’s work is set apart by a distinctive quality. The low contrast and rich grey tones of his photographs capture an often dispersed or subdued light, conveying the atmosphere of Scandinavia’s short winter days, the muffled silence of snow and its odd luminosity.

It is easy to make links between Smolianksy’s work and that of others; he is often compared to European photographers, such as André Kertész, yet influences from America are also evident, in particular the street abstracts of Aaron Siskind. One photograph (Saltsjö-Boo 1979), which captures a beam of sunlight crossing an unmade bed, is reminiscent of Nan Goldin’s Empty Beds, taken in the same year. However, where the details and full colour of Goldin’s image feel confessional, Smoliansky’s simpler image draws the viewer’s attention to the forms created by creases in the sheets and discloses a restrained poetry in this private moment of noticing.

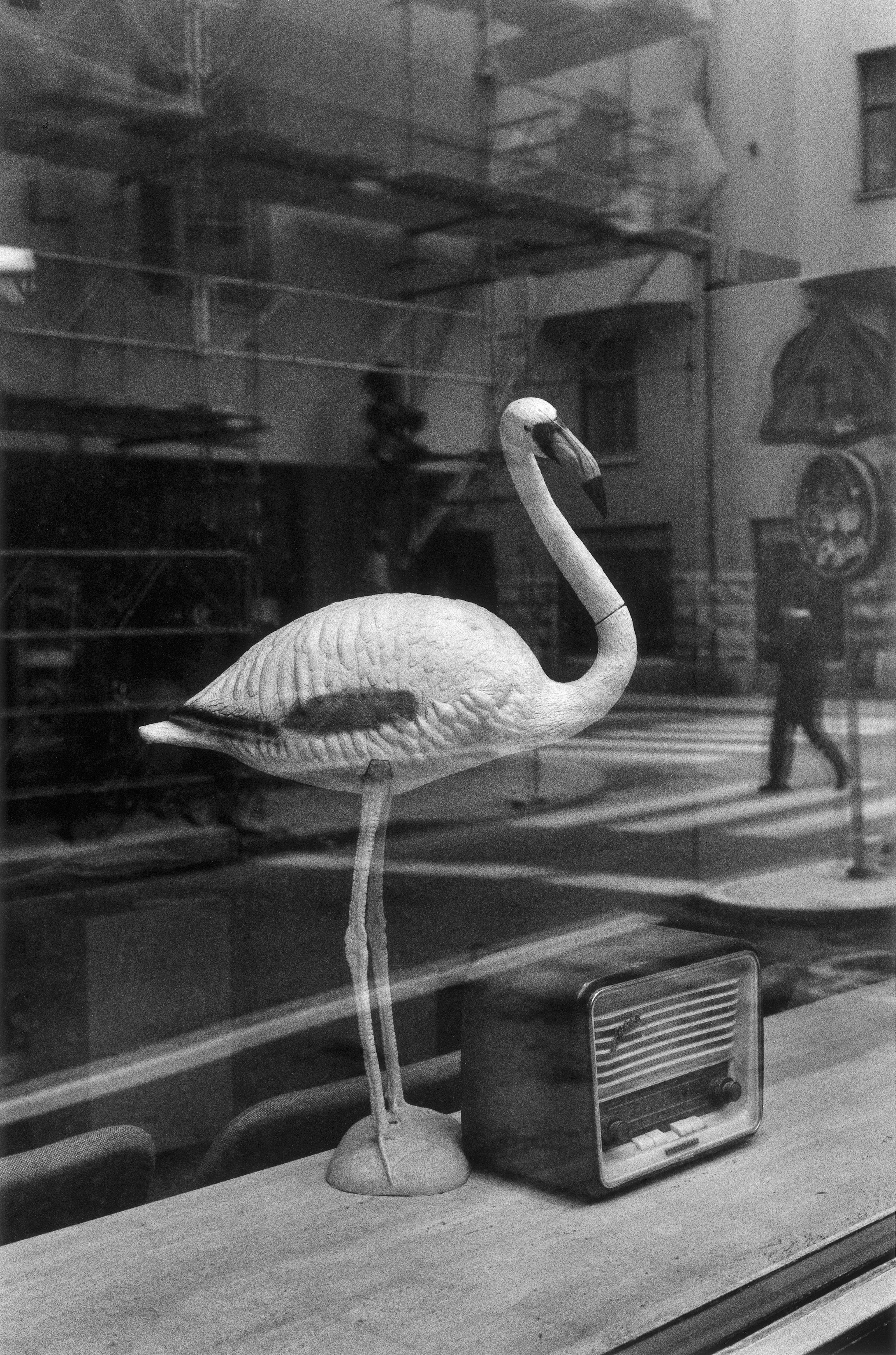

Many of his photographs possess a timeless quality, a flippant explanation for which could be Smoliansky’s traditional use of film, which he hand processes and prints. But equally this anachronistic feeling is the result of strict composition and a selective eye that seems to have transcended change over the decades, excluding all signs of the contemporary. A model flamingo stands in a shop window next to a wireless radio, a shadowy figure crossing the street is reflected in the window, but there is little, apart from the title (Södermalm 2002), to locate this photograph in our century.

A brooding anxiety permeates several photographs featuring couples on the street, as if Smolianksy is trespassing on intimate moments. His camera peers through a car window capturing a man playing with his girlfriend’s hair and the echo between a tattoo on the man’s hand and the pattern of the woman’s blouse. In another a man wrapped in a black overcoat glares with a half sneer over his shoulder straight at the camera, an arm protectively around his girl, her face entirely hidden. Smolianksy is not an objective observer recording what he sees on the street; rather he uses what he encounters as material for narrative imaginings.

The dramatic quality of Smolianksy’s photographs has led to them being described as cinematic and, unsurprisingly, comparisons are often drawn with filmmaker Ingmar Bergman; in particular the sinister atmosphere of Bergman’s 1966 classic Persona comes to mind, with it’s intense close ups of faces that teeter towards abstraction.

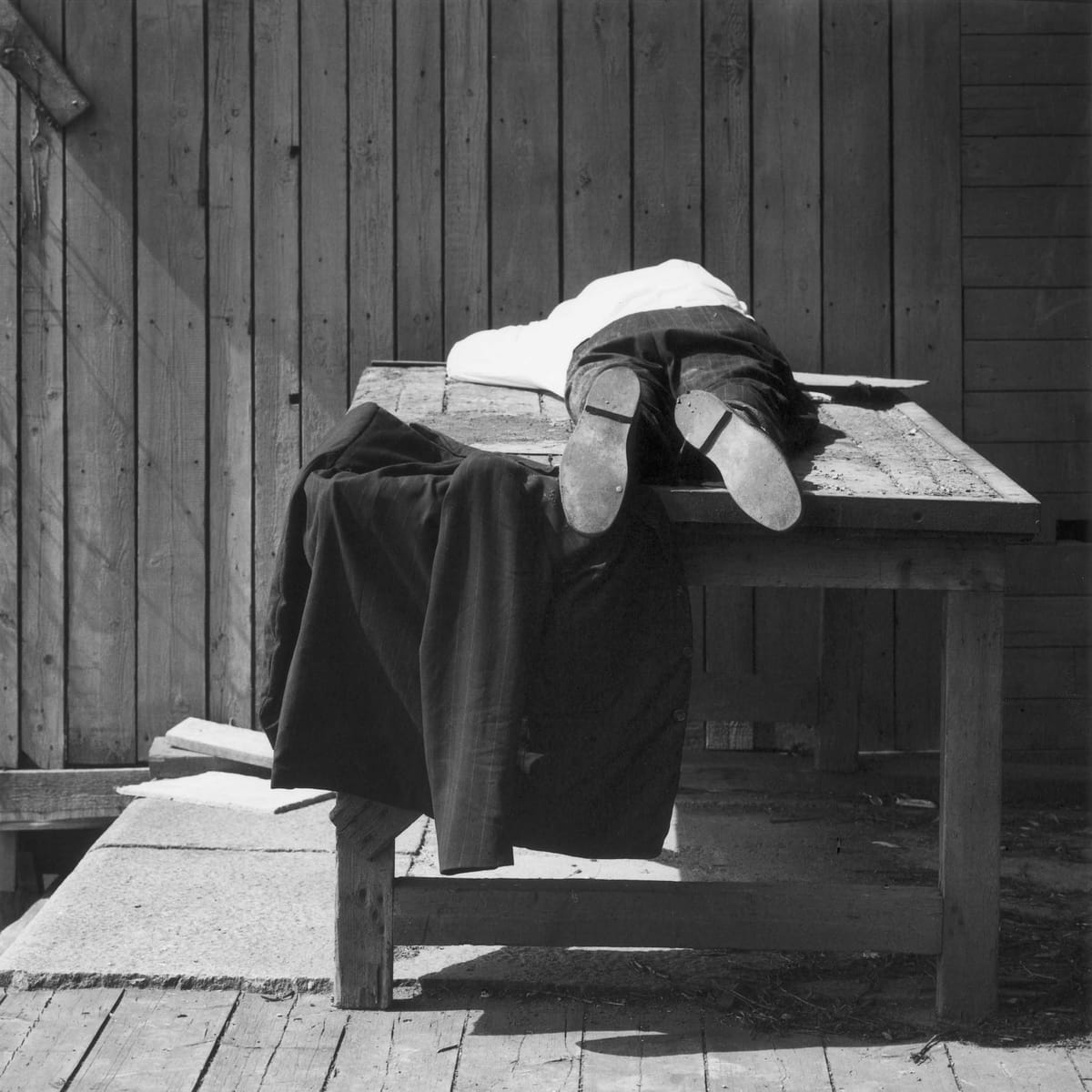

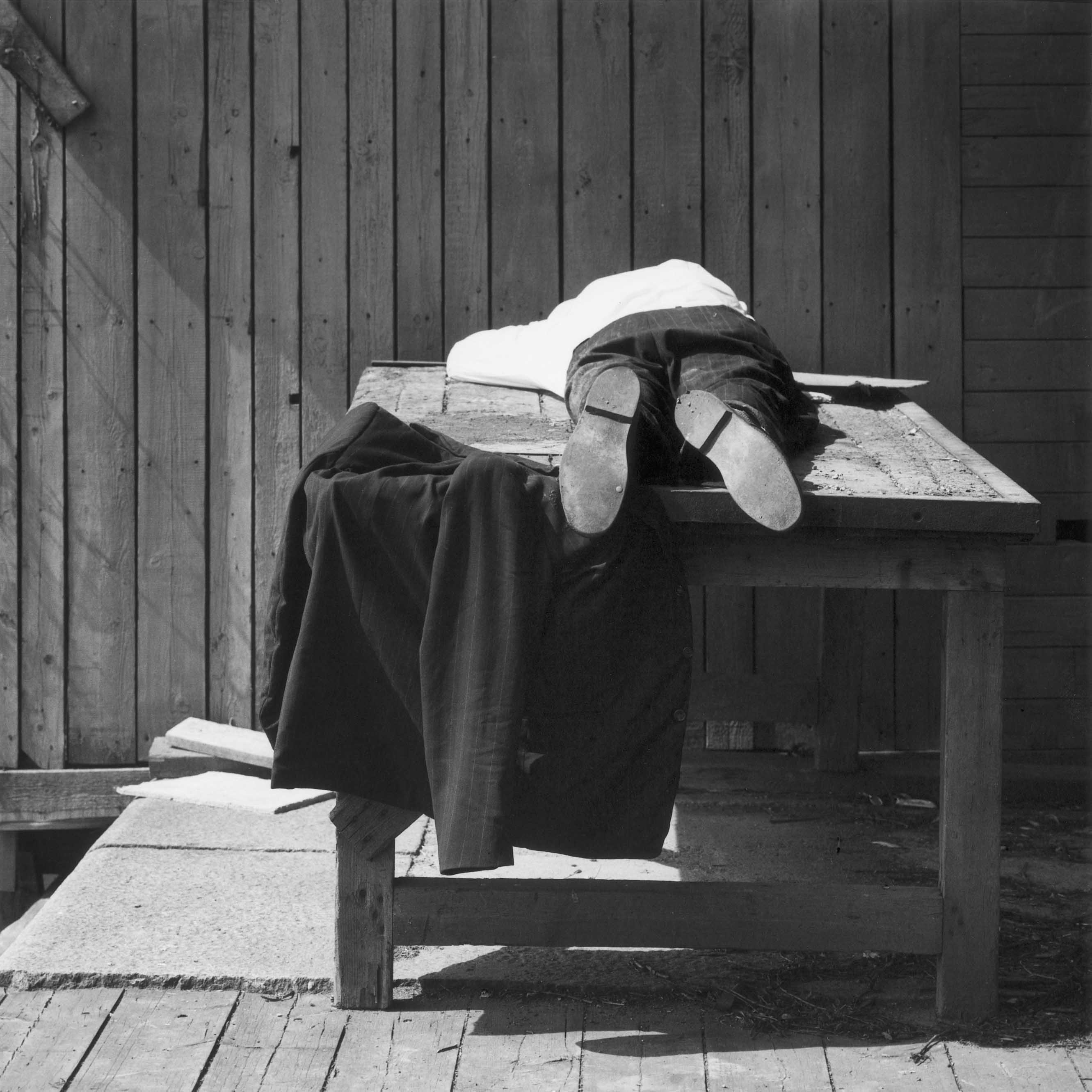

The more recent images on display tend to focus less on people, instead taking advantage of the graphic appearance of human traces within rural and urban landscapes. Smolianksy states an interest in making “something out of nothing” but it feels like his more abstract images reveal a hidden order. His strict framing creates elegant geometry from tire marks melted through a snow-covered highway, or prompts the viewer to look for patterns in the silhouette of a tree stretched across a blank white sky. Smoliansky also draws out the camera’s ability to confuse. An architectural detail, perhaps the porthole of a boat, turns out to be a close up of a broken pair of spectacles. A ladder is caught floating on a chain across a cloudy sky, and disturbingly it is impossible to discern whether we are gazing up or down. Gravity has been suspended along with time.

The idiosyncratic, subdued yet poignant world Smoliansky’s camera captures is well worth exploring for the visual quirks he provides. Whether we are unsure of the decade we are looking at or the direction the camera points, the disorientation caused by these optical slips provides a bracing reminder that all is not as the camera portrays it.

gunnarsmoliansky.se

michaelhoppengallery.com