Beijing-based designer Solveig Suess considers the power of memes and why a sex-tape filmed in the changing rooms of a Beijing branch of Uniqlo went viral in China.

Last week a friend in one of my social network groups posted what looked like a retail image of a white t-shirt, with a black and white graphic slipped under a red Uniqlo logo. “Love the t-shirt!! Is it on Taobao yet?”, “Mine comes in tomorrow. We can share”. More streams of fake Uniqlo PR images continued to pop up on my social media feed throughout the day, followed by an endless stream of Western articles speculating on what this might say about the sexuality amongst the entire youth population of China.

On the 15th of July, a leaked sex-tape went viral across Chinese social media. This seventy-second phone-recorded video was of a heterosexual couple having sex in the changing rooms of Beijing’s flagship Uniqlo store. The video, low-res and shaky, somehow found its way through the cracks of what is normally a controlled circulation of data and images of the Chinese internet. By the time of my discovery, a few hours after the leak, the video had already been taken down. All that was left were self-generating images, which instead took life of their own. Stills were taken from the video, edited or referenced, then posted through various WeChat 'moments', or social media walls. In the book In Defence of the Poor Image, Hito Steryl writes, “…the poor image is a copy in motion. Its quality is bad, its resolution substandard. As it accelerates, it deteriorates. It is a ghost of an image, a preview, a thumbnail, an errant idea, an itinerant image distributed for free, squeezed through slow digital connections, compressed, reproduced, ripped, remixed, as well as copied and pasted into other channels of distribution.” It could almost be a direct description of the stills taken from this changing room recording.

With 700 million Chinese citizens equipped with smart phones, each is weaponised with the technology to capture, upload, share, comment and watch. The video, taken down within a few hours, attained a kind of cult-like status amongst the few thousands that managed to save the video or hide it in a virtual safe place. Even without the video, the image remained powerful; the 'original' became less important as its 'ghosts' sprawled the social networks and it gained more momentum as it slipped between the virtual and physical. With most of China's phone users utilising WeChat, the messenger, social network and media app, these images spread through thousands of networks within a few hours of the leak. “The poor image is no longer about the real thing – the originary original. Instead, it is about its own real conditions of existence: about swarm circulation, digital dispersion, fractured and flexible temporalities,” write Hito Steryl.

Uniqlo is one of Asia’s largest fashion retailers, with its brand strategy aiming to “transcend all categories and social groups … going beyond age, gender, occupation and other ways that define who people are,” according to their website. It has hence taken form as a dull, quiet, neutral brand. One can only speculate what made the meme this contagious for so many people to desire involvement. Was it the image of the brand jarring against the stills taken from the promiscuous video filmed secretly in its changing rooms that made it so absurd? Or perhaps that the act itself demonstrated a certain dynamic between the sexes: the man holding his iPhone, fully dressed in black, recording the completely exposed woman, who was dispassionately performing while looking at herself in the mirror. Or perhaps it was in fact the act of sneaky disobedience also occurring so close to the open public and commercial sphere – the viewers might have related to having been in the position of the customers, or even the couple. Design collective Metahaven, in Can Jokes Bring Down Governments, describe the meme's nature as 'nonsensical', but because of this, it becomes a disruption to the existing systems that it circulates within. “Design-as-meme is a focal point for tacit ideological coordination, a public in-joke, a general strike of common sense-making,” Metahaven writes.

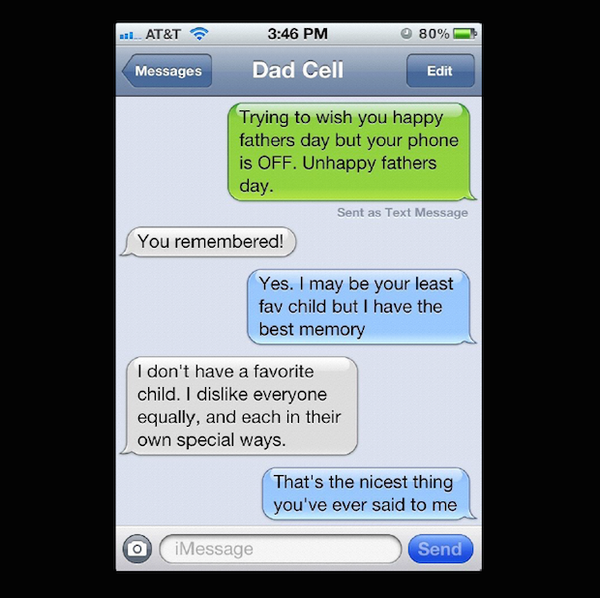

Many of the brand’s previous PR designs suddenly became potential templates for adaptations of the meme. People riffed on the consumerist formats of Uniqlo’s brand and disrupted its image by overlaying the video stills with Uniqlo’s red logo or white type. T-shirts were designed, so were advertisements, catchphrases, tattoos and even (and perhaps most fittingly), cake decor. Selfies were taken in front of the Uniqlo logo or its stores and then uploaded. Anyone is able to participate and author their own combination of this meme, anyone can make fun of the brand, laugh at our culture of consumption, and chuckle at the ruling party’s inability to control a meme. Through these exchanges of jokes and with the knowledge of the video being illicit, these became entertaining little acts of disobedience themselves. “Jokes are political weapons which deny an opponent control over the terms of exchange by ignoring those terms entirely,” writes Metahaven, Can Jokes Bring Down Governments.

Media articles twisted and churned, adding their own narratives to the event while an online ‘human flesh search’ surged rapidly by the netizens. Caught in a hunger-frenzied search for more entertainment, some netizens scoured the networks to expose the personal lives of the characters featured in the film, taking no longer than a day for them to find out the characters' names, identity card numbers, university names, and dates of birth.

Within a day, the meme had also succumbed to national and commercial agendas. With so much attention from the press and people, the CCP's internet regulation wing deemed this as an act severely against the nation's socialist core values. The participants, uploaders and initial spreaders were found through WeChat's monitored and easily traceable networks, charged and put in jail until further notice. Meanwhile, Uniqlo’s stocks skyrocketed in value due to the sudden shoot of its online search popularity. H&M and Zara piggybacked on commercial opportunities to advertise their larger changing rooms to 'get in on the joke'.

Now when searching on Chinese web browser Baidu for traces of the Uniqlo meme, nothing but the average commercial images show up, with the only debris of the video left on personal WeChat histories. Shadow narratives persisted through networks with ghost articles whispering rumours of the female participant's suicide.

solveigsuess.com

Solveig Suess

…is a research-led graphic designer based in Beijing who will be joining the Research Architecture MA in Goldsmiths this autumn. She is the co-founder and designer for Concrete Flux, primarily a journal on urban spaces in China, and has just completed six months working with Metahaven.

Meme

…is a word coined by Richard Dawkins in his 1976 book The Selfish Gene, as an attempt to explain the way cultural information spreads. In 2013 Dawkins characterised an Internet meme as being a meme deliberately altered by human creativity – distinguished from Dawkins' pre-Internet concept of a meme which involved mutation by random change and spreading through accurate replication. Dawkins explained that Internet memes are thus a "hijacking of the original idea," the very idea of a meme having mutated and evolved in a new direction.