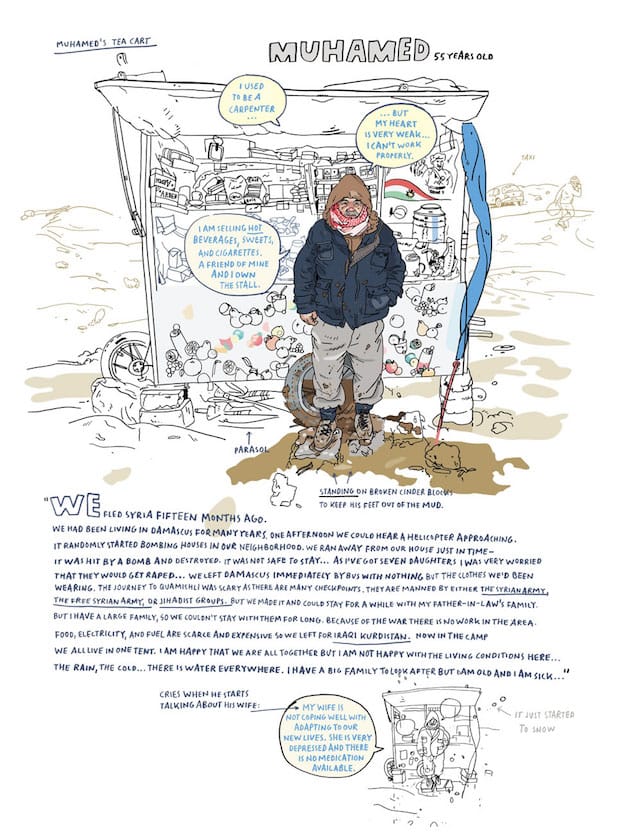

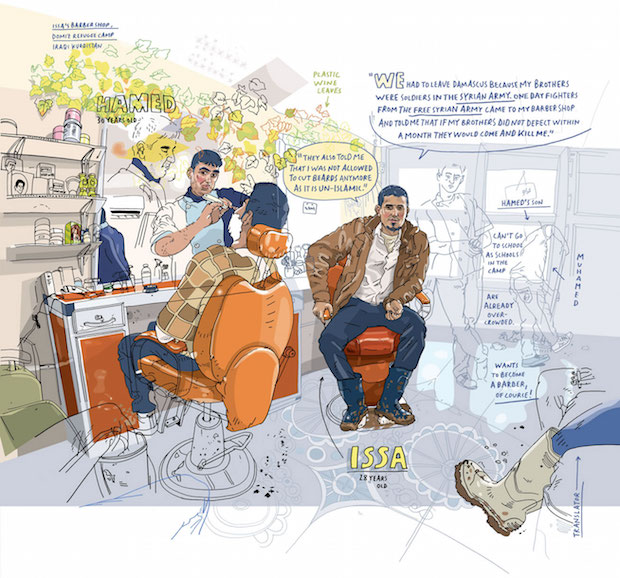

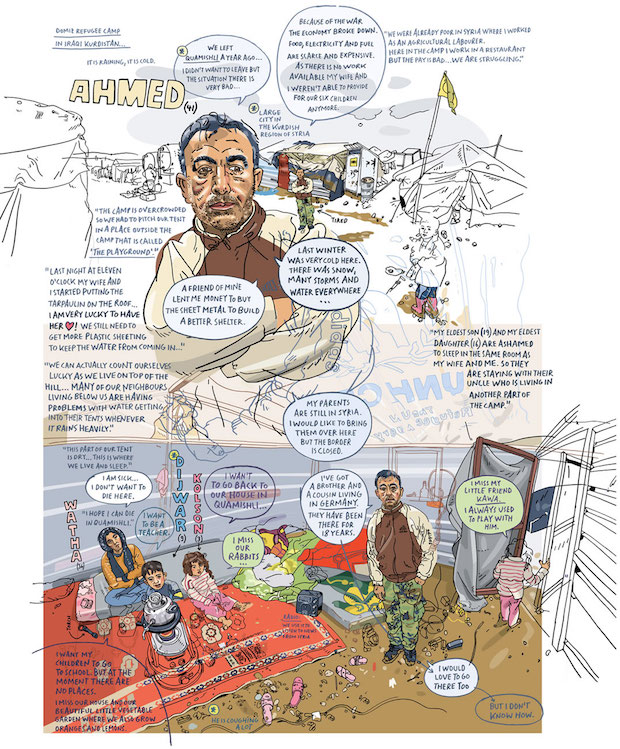

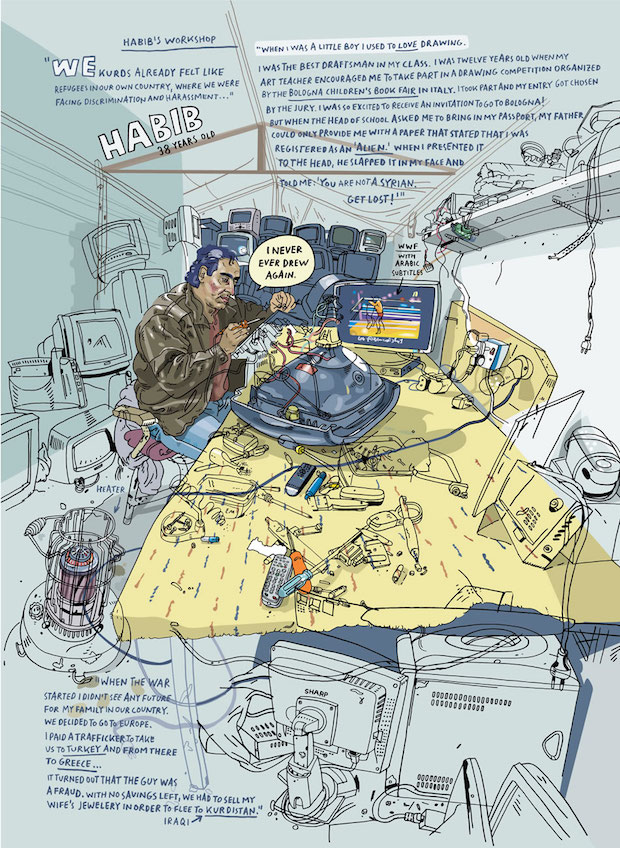

Recently nominated for the World Illustration Awards, Olivier Kugler’s drawings from the Domiz refugee camp in Iraqi Kurdistan combine portraits of the displaced Syrian people living there with their stories. We caught up with Kugler to find out more about this important project.

How did the invitation from Medicines Sans Frontiers to spend two weeks in Iraqi Kurdistan come about?

The Swiss chapter of MSF became aware of my work through the publication of my book Mit dem Elefanten Doktor in Laos, which had just been published a couple of months previously in Germany and Switzerland. The book is a documentation about a young veterinarian I joined on a mission to remote logging camps in Laos where he is looking after the health of working elephants.

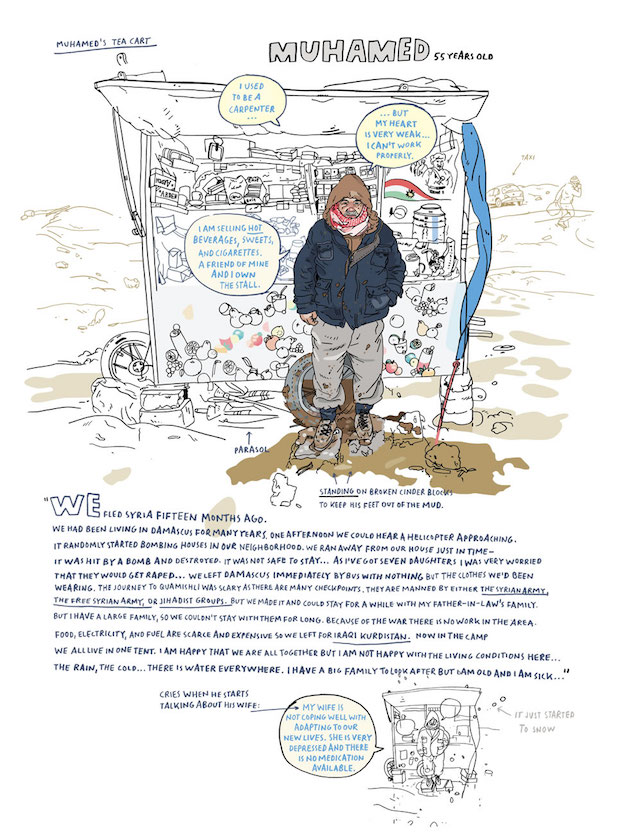

MSF asked me to produce a series of drawings documenting the circumstances of refugees in Domiz refugee camp. The aim was to exhibit the drawings at the FUMETTO International Comix Festival in Lucerne and to get them published internationally in magazines and newspapers.

To gather reference material I travelled to Iraqi Kurdistan where I spent the first two weeks of December 2013 with the MSF field team working in Domiz. During this time I conducted many interviews and took countless reference photos of the Syrian refugees I met.

Tell us a little bit about your experience of being there. How did it surprise you?

Even though I was well aware of the circumstances of Syria's displaced people before I went to the camp, meeting the refugees in person was an intense but also an enriching experience. Obviously it was very emotional meeting people who have just fled a war zone and listening to their stories. For example, I met a grandfather who witnessed his whole house and belongings getting destroyed by a barrel bomb in Damascus, a young mother of two, whose husband, a political activist, vanished in a prison run by the secret police and the family of an impoverished rural worker who had to leave their home town because the economy broke down and there was no more employment to be found.

The most intense situation was when I interviewed the young mother mentioned above, whose husband disappeared in the secret police jail. The woman fled Syria with her two little daughters. She told me: "When my girls see the children of our neighbours in the camp playing with their fathers they get very sad… It is too hard. It breaks my heart". We had to stop the interview when the lady started to cry and found it to hard to further talk about her experiences.

What was the aim of your drawings? How did you choose which people to include?

At the time there was hardly any mention in the media about the Syrian refugees in Iraqi Kurdistan in general and the Domiz refugee camp in particular. The media was mainly reporting about the large refugee camps in Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey. The aim of the drawings was to raise awareness of the refugees circumstances in Domiz camp where MSF is looking after the health of the displaced people.

Tell us a little bit about the experience of actually making the drawings. Were people receptive?

I didn't really do any drawings on location in the camp. During my stay I did a small number of rough sketches but I concentrated on talking with a lot of people, learning about their experiences, their circumstances and photographing them in their environment.

The men I talked to were mainly receptive. I found it difficult though to talk with and photograph women. Due to traditional and cultural circumstances, women (or their husbands and fathers) often weren't keen on me depicting them. The few women I was able to draw were either employees of MSF or their patients.

There were some men, mainly older men, who were happy to tell me about their experiences in Syria before and during the war but didn't want me to draw them as they thought they, or their relatives, could somehow get into trouble with one of the belligerent factions. There were also some young men who run away from the army who didn't want me to draw their faces.

What did you find was the most challenging part of the project?

As mentioned, I wanted to do some drawings depicting women to document their experiences of war and of being a refugee. There are a number of beauty parlours in the camp, there are even one or two shops renting out wedding dresses. I really wanted to draw a beautician in her salon but unfortunately there was no chance.

How did you adapt the drawings once you returned home?

During my stay I interviewed dozens of people and took countless reference photos. Upon my return home I kind of knew already which of the people I wanted to draw. I did several rough sketches with notes which I sent to Stacey Clarkson, the art director at HARPER's in New York, to give her a better idea about the people I wanted to depict. Once the sketches were approved I started working on the large pencil drawings ( A1 format). I then scanned them and worked on the colouring and the composition and layout digitally. While I worked on the drawing I listened to the recorded interviews. After each drawing was finished I listened to interview again and edited them, before hand-writing the text, scanning it and finally placing it into the drawing.

olivierkugler.com