With recurring themes of change, vernacular culture and identity, new book The Open Road: Photography & The American Road Trip documents the social significance of this cross-country journey through the work of eighteen photographers.

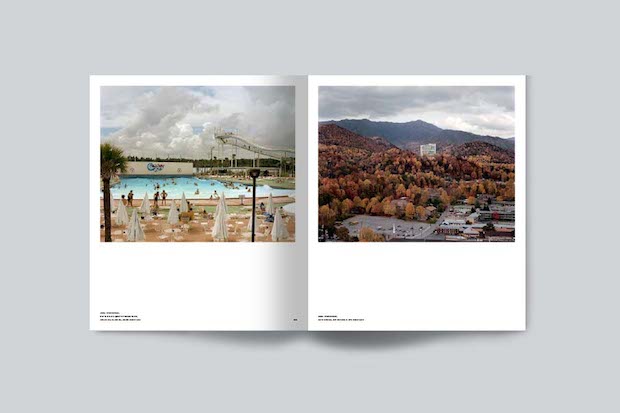

Given the incredible scale of the United States of America, the road trip is more or less inevitable. But since the very first days of the automotive industry, this cross-country journey has penetrated the core of American cultural identity and developed into something much more meaningful than the act of getting from A to B. It’s a semi-spiritual quest that pits the individual against the vastness of their nation and the huge range of human existence they encounter along the way.

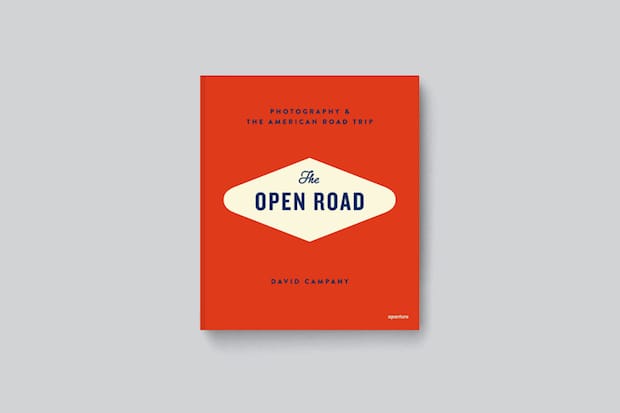

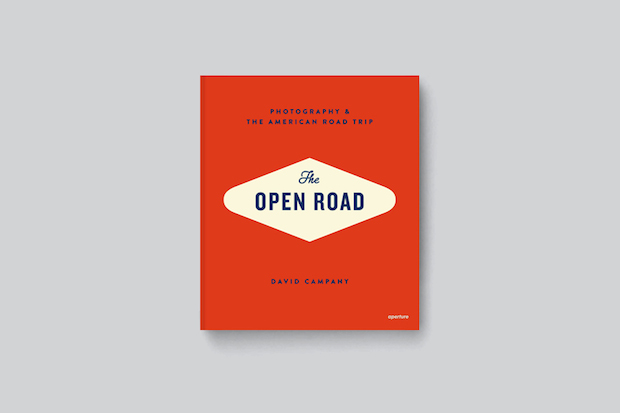

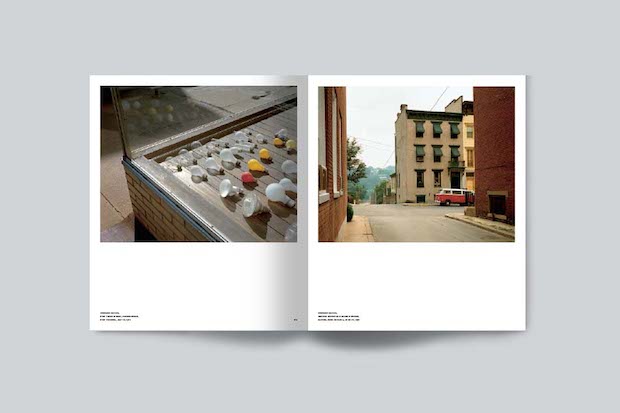

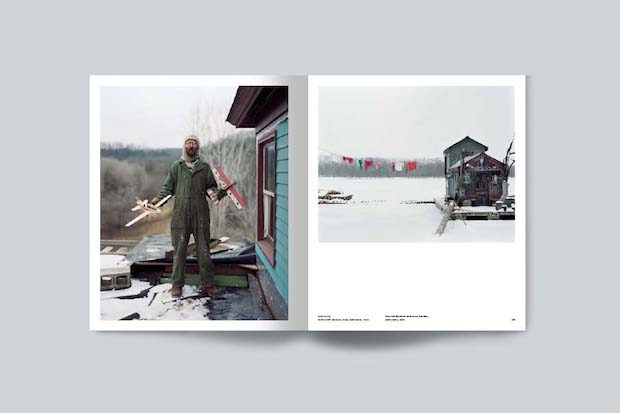

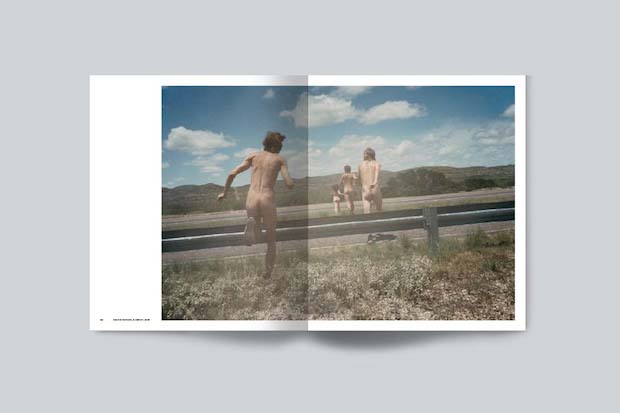

Unsurprisingly, considering its scope to explore both what America is and the human condition more generally, the road trip is a theme often visited by artists, either touching on it to explain their homeland and their own identity or presenting it as something other. The Open Road: Photography & The American Road Trip by David Campany and published by Aperture is a new book that looks at eighteen photographers who have journeyed across the United States, starting from the black and white reportage of Robert Frank in 1955 and moving right through to the playful manipulation of Taiyo Onorato and Nico Krebs in 2008 and the spirited nudes of Ryan McGuinley from 2014.

Campany’s excellent introduction is not just a history of the road trip but works as a concise but insightful narrative of both the photographic medium and of the social-economic evolution of America. In it, he discusses one of the earliest examples of road trip photography, the Photo-Auto Guides dating from 1906. In a time when there was little signage or even road names, these very early predecessors of Google Street View presented a driver with step-by-step directions using images of landmarks on their journey. Twenty-five were published over five years, the most ambitious of which stretched from New York to Chicago.

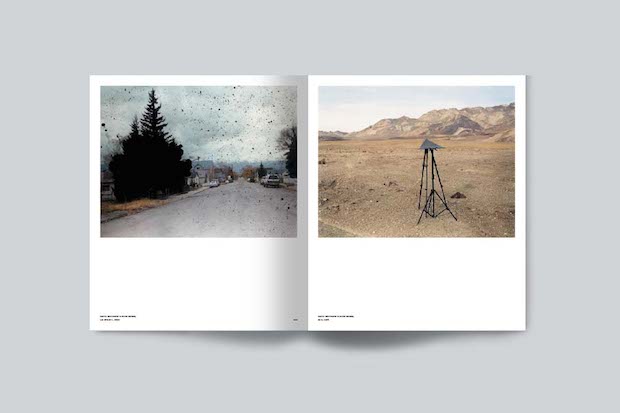

Unfortunately these guides were a victim to the automotive industry’s success. As travelling by road became more popular, the roadsides transformed beyond recognition and the Photo-Auto Guides could not keep up with the changing landmarks. But it is this change, and the friction between old and new, that is perhaps the key to what is so compelling about the road trip. In his discussion of Walter Evans, the first photographer to have a solo show at the MoMa (in 1938), Campany points out that he preferred to photograph smaller towns chanced upon by car rather than sprawling urban domains. Campany writes: “Here one could see new technology rubbing along with the vernacular culture and a practical acceptance of the past. This mixture, thought Evans, provided the truest measure of the state of the nation.”

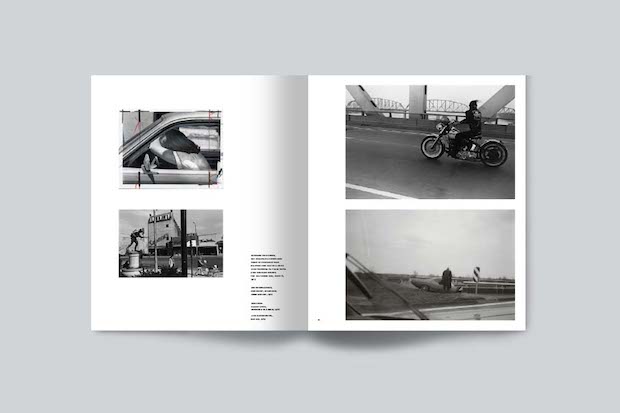

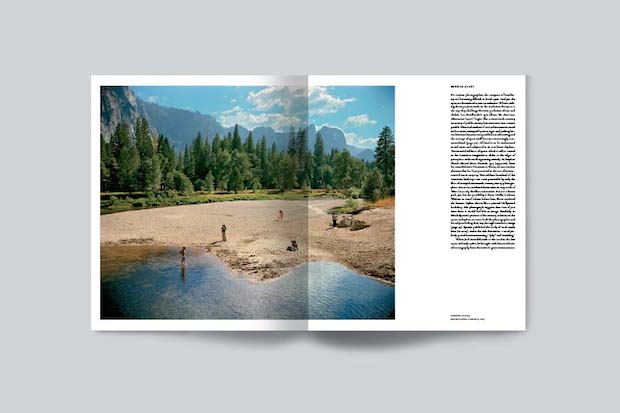

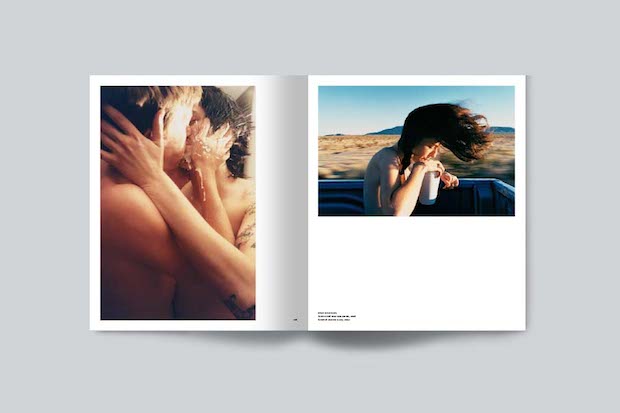

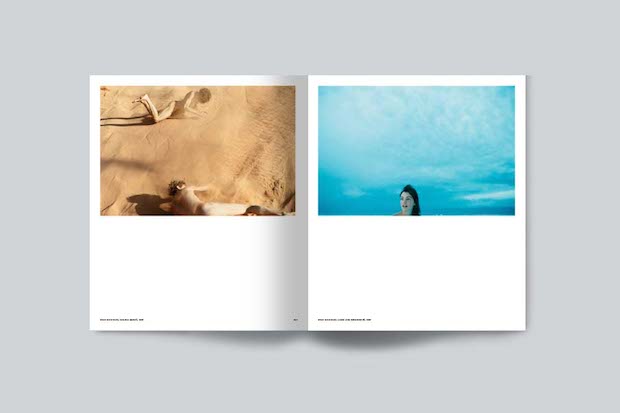

Despite the recurring themes of change, vernacular culture and identity, the eighteen photographers that Campany has collected in this excellent book have captured very different Americas. Swiss-born fashion photographer Robert Frank, for example, presents a Fifties landscape far from the rosy projection of post-war comfort and confidence more common among his peers. In two of the most striking images in this section, as at many points in the book, the camera is treated with suspicion. A white woman raises an eyebrow from a segregated trolley cart in New Orleans and two New Jersey residents peer cynically from behind their shuttered windows, the face of the female obstructed by an American flag. In complete contrast, Ryan McGuinley’s joyful nudes (dating from 2004-2014) speak of unreserved passion, uninhibited youth and angst-free (often amusing) exploration of America’s landscapes. However different, both (like many of the photographers in the book) offer unexpected viewpoints on the country, both at odds with the conventional narratives of their times.

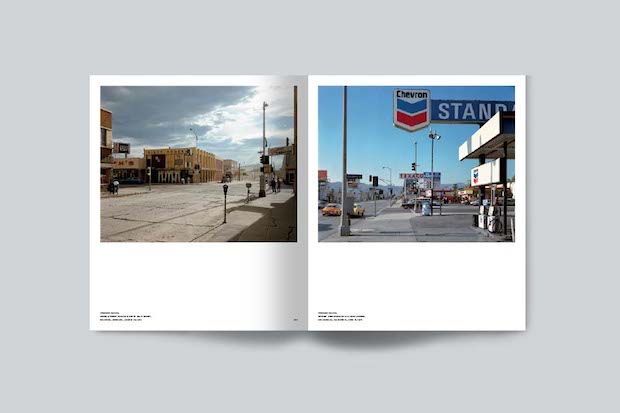

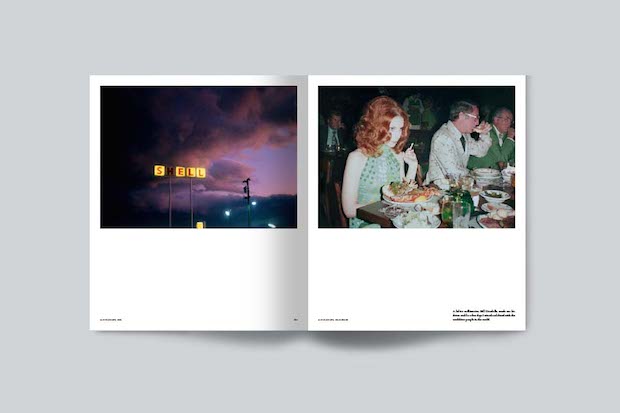

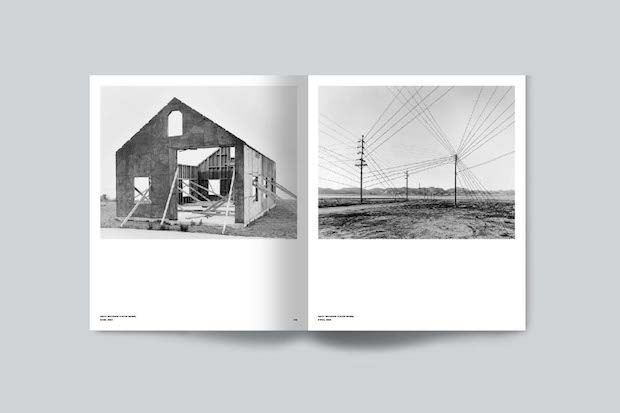

For some of the book’s photographers, it is roadside architecture that is the vehicle they have chosen to explore America’s narrative. Distinctively graphic in its style, Ed Ruscha’s Twentysix Gasoline Stations is a factual record of these buildings and a publication that because of its flat, purposely anti-sentimental approach is now seen as a key work of Pop Art. In a similar way, Lee Friedlander’s series of photographed monuments sometimes appear austere and traditional, but at times almost post-modern in their juxtaposition with the visual cues of everyday mundanity, such as the advertising buzz of Times Square.

As you’d expect, there’s a huge amount of artistry in this well-curated selection. Alec Soth’s dream-like, almost suspended compositions are a particular highlight, as is the painterly approach of Todd Hido’s foggy atmospheres, shot on medium format and developed himself. There are some incredible moments too. Joel Meyerowitz’s chapter features a shot of a woman bathing in New York state’s Anawanda Lake, captured just at the point where she is flinging her crutches into the waters. In some chapters, the focus is turned around on the photographer themselves. The images of Danish photographer Jacob Holdt, who hitch-hiked around America for five years covering 113,750 miles and selling his plasma to blood banks to be able to eat, say just as much about his character and personal story as the strangers (themselves largely impoverished African-Americans) that offered him accommodation, food and friendship.

With such varied subject matter and styles, it was important that the book’s design (by Frieze art director Sonya Dyakova) did not interrupt the images but simply communicated what the book was about. Inspired by vintage road maps, Dyakova has hinted at this characterful graphic heritage without ever resorting to nostalgia. Sophisticated use of typography, namely keeping the playful, scriptive typefaces well away from the photography, is key to this book’s success. It’s a thoughtful project – both in curation and design – and a book that goes a long way to demonstrate what a powerful and multi-faceted experience the road trip can be.

The Open Road: Photography & The American Road Trip by David Campany

Published by Aperture, £40

Designed by Sonya Dyakova