An impressive and entertaining piece of design writing that will hook you in with its very personal take on design legend Otl Aicher's life and work...

At Grafik we are always excited to discover a talented new voice in design writing. Young designer Marius Schwarz impressed us with his independently published pamphlet on Rotis — the rural studio of German design grandee Otl Aicher, whose radical approach to design is epitomised to his much admired work for the Munich Summer Olympic Games of 1972. Schwarz's essay unfolds through a personal narrative, describing a research process that was sparked by a family connection with Aicher and which took him to visit several people who were central to Aicher's life and work. Schwarz lifts the lid on a unique design mind, from little eccentricities to fundamental traits that defined his unique oeuvre. Here, we present the first four chapters of Schwarz's essay The Green Our Sheep Graze...

Our sheep

Last summer when I skyped with my parents we ended up talking about Rotis, a small settlement not far from their place. I told them that I kept wondering how it must have been in the 1970s and 1980s, when graphic designer Otl Aicher ran a studio down there with up to a dozen assistants, right out in the middle of nowhere – in the alpine upland of Allgäu, South Germany.

‘Rotis?’ my mother asked, ‘funny you mention that. A few weeks ago his sons called to ask if they could borrow some of our sheep, to maintain the fields of their property.’

Our sheep grazing the fields of Rotis – it took me a while to process that.

As far as I knew, Aicher mentioned that he would in no circumstances let sheep take care of his lawn. They would only ruin it, he said. Instead, I heard, he mowed his vast yard weekly, on a lawnmower. And only when the grass was trimmed evenly was he pleased and ready to put the tractor back into the garage.

After 20 years in Rotis, Aicher’s studio came to a sudden end. Without a doubt a tragic story, but also one of absurd symbolic power. Aicher’s accuracy was tireless. To avoid visible turning marks on his lawn he used to ride his tractor onto the street and turn it there. This allowed him to continue the following line with a straight start.

I can only guess how many rows he finished that late August day in 1991, when a motorcycle, coming from Bavaria, hit him on his very last turn. A week later Aicher, one of the most notable designers of post-war Germany, succumbed to his head injuries in a hospital in Günzburg.

The last turn on the lawnmower, that’s how Aicher’s idea of Rotis ends – our sheep on the lawn, that’s how this story begins. It is a story about a man’s desire for order and control among the chaos of reality. About success and meaning of the past and the subsequent disillusion of its heirs. Finally, about the decay of a modernist architectural monument in a landscape of ancient farmhouses.

And about me, digging my way through history.

A storyteller

My first investigation of Rotis started with a rumour. A rumour that I had already picked up years ago in the only good pub in the town where I grew up: Gasthaus Lamm, or ‘Lamm’ as the locals would call it. The rumour claimed that when Aicher moved to Rotis in 1972 he built his ateliers on stilts to avoid an official building permission. A mischievous trick.

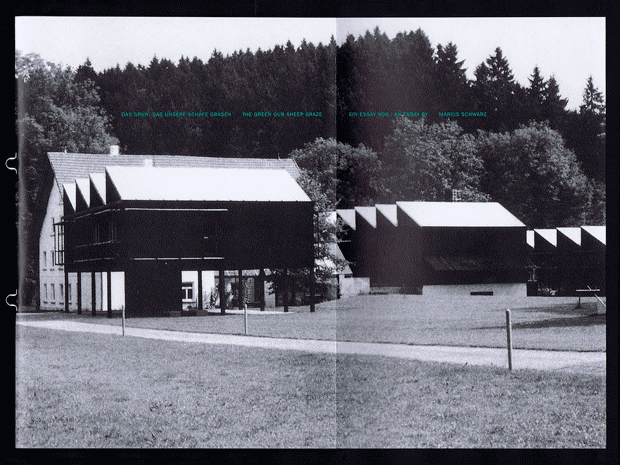

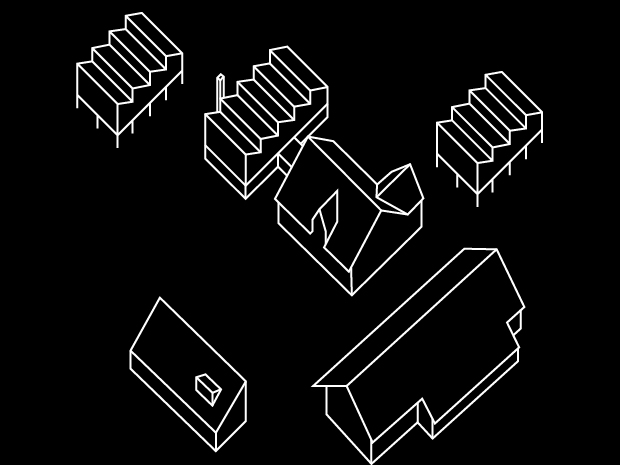

Apparently he would fully erect the houses without any papers, and when the building department sent their wrecking balls, he referred to the departments very own guideline book which, according to the rumour, said: ‘only this is a building, and therefore in need for permission, that has a floor area of three metres-square or more’. Aicher’s ateliers float two meters above ground – therefore wouldn’t be buildings in that sense.

Along with the two ateliers on stilts, Aicher rebuilt the old Rotis saw shed into a hall, likewise covered by shed roofs. He erected a garage, a long building with a lean-to roof. And he developed the old mill house and cowshed, the classic gabled roof buildings.

The stilt story stuck in my mind, even though I was aware of the circumstances in which it was told. The amount of heavy local beers which are known for loosening tongues, tended to make storytellers ignore facts to make their stories sound better.

The next day I called the father of a friend who I knew was a city planner in the town hall. I told him the story, hoping to find out if there was something to it or not. He had never heard about it, but as he was equally impressed by the idea he sent an assistant into the archive.

He returned my call two days later to report: ‘It’s a riddle to me, Aicher’s file contains neither remarks nor communication. It is totally blank!’

I had forgotten about the whole thing – until coincidence brought it back.

In the following summer holiday the quarterfinals of the UEFA Euro Championship were being screened in front of Lamm. Greece vs Germany. A bitter defeat, especially in regard to the upcoming Greek economic crisis.

After the final whistle, I talked to the same guy again – the stilt-story-guy. A city original and long-term patron of Lamm, secretly nicknamed ‘Captain Jack Sparrow’ due to his wooden walk, long greasy hair and the hat he wears.

‘You’re still interested in that?’ he asked, ‘then you should talk to Julian’. He pointed in the direction of a hefty, bald guy in his fifties, sitting broadly at the very last beer table. ‘I’ll introduce you to him.’

As we approached the guy I noticed his similarity to Aicher.

‘So so,’ he said in the voice of a Swabian trying to speak German, ‘yet another one interested in Mr. Aicher.’

The game is now almost two years ago. In the meantime I have read everything on Otl Aicher and Rotis I could get a hold of. I went into Aicher’s archive, talked to two of his former assistants and visited his son Julian down in today’s Rotis.

The design officer

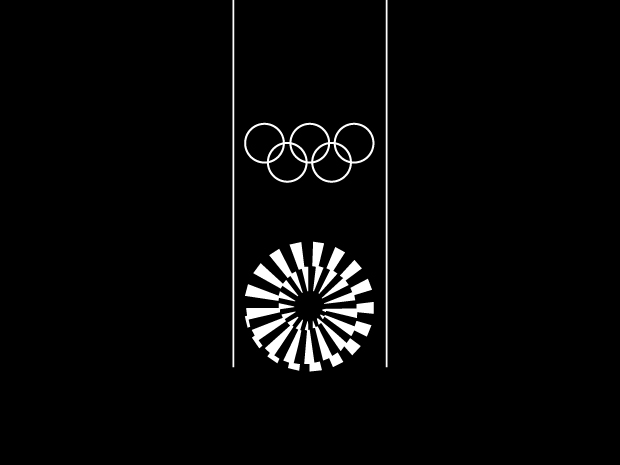

But to fully understand Aicher’s Rotis we have to go further back in time. To Munich in 1972, into the last preparations of the Olympic Games, onto the office floor where Aicher worked as the design officer.

For four years he had been directing a team of assistants who helped him execute his concept: cheerful, peaceful and non-political games. The idea was to radically oppose the 1936 Berlin games which had been abused for Nazi propaganda. The Nazis whose system Aicher deeply detested and whose flag he had deserted in the Second World War. Aicher’s team put traditional Munich in a modernist jacket. They replaced the totalitarian system of the Nazis by their own system, one of bright colours and clear lines.

Orange, yellow, blue and green posters, flags and signs were printed and hung throughout the city. They showed athletes of all disciplines, screened in bright pantone-colours, labelled with the Olympic logo, Aicher’s spiral logo and ‘München 1972’ written in an expressionless typeface. Booklets, backstage passes, uniforms – everything you can imagine was designed, produced and delivered. There was a plastic dachshund named ‘Waldi’, the Olympic mascot, and a blue nylon version of the Bavarian dirndl for the volunteering hostesses.

The decreasing pressure in the office allowed Aicher to think about the time after the games. He played with the idea of a radical change; to retire to the countryside with both his studio and family. When a friend showed him the abandoned mill in Rotis he knew right away: ‘This is it!’ While he was wandering on the mill terrain he drew buildings in his mind, and back at the office desk in Munich he sketched them with a ballpoint pen.

Once the housing for his new studio was found, the next step was to look for good assistants.

A week before the Olympics began Aicher invited Monika Maus for a job interview; a technical drawer from Ulm, long term assistant of hfg colleague Walter Zischegg, who recommended her.

Aicher showed her around the busy office. Walking from table to table he talked enthusiastically about his plans. In between talking, he bent over his assistants’ drawing tables, either giving a satisfied nod or making a quick sketch for corrections. When they reached the end of the room, he turned around and asked the girl with the confident smile and the dark pageboy hair, ‘Can I count on you, Mrs. Maus?’

Monika who followed him in silence had already been impressed by the colourful designs when she saw them on the way from the train station to the office. She was, without question, interested in working for this man, but she had doubts about the rural remoteness of the new studio and the consequences it would have on her life. So she replied straightforwardly: ‘I think I have to see this place first, Mr. Aicher, before I can make a commitment.’

‘Hoppla!’, Aicher said, and talking of himself in third person: ‘An Aicher didn’t hear such a thing in a long time.’

But because he appreciated her directness, he promised: ‘I’ll make sure that you get to see Rotis as soon as the constructions begin.’

At the end he advised her to visit the coffee shop on the second story because its terrace gave such a good view over the Olympic Village.

‘Thanks Mr. Aicher, I was walking around the Village the entire morning. The view won’t be too surprising.’

Now honestly impressed, Aicher said: ‘Moni’ – and this is how he called her the following five years – ‘People who sneak past the guards to get access to the Village, that’s exactly the kind of workers I need for Rotis.’

The assistant

I have an appointment in the former hfg Ulm, the legendary design school in whose foundation Aicher and his wife were majorly involved. The building, designed by Max Bill, is used as a public museum and an archive today.

The thoroughly modernist construction is fully cast in concrete but still manages to keep a certain lightness. It might be the thin wooden planks in which Bill panelled parts of the walls, or the infinite amount of light that comes in through the big window facades.

The building is largely preserved in its original state. It is only the glass of the aforementioned windows that reveal its present time: the old ones were simply not available anymore when the city of Ulm restored the building – that’s why the complex shimmers in this omnipresent blue today. Disregarding this detail, its visitors are able to experience, as if in an architectural time machine, how it must have been once. The famous curved wooden bar still meanders its way through the canteen. Only the hfg students with their ironed shirts and slim ties are long gone when Monika Maus enters, this afternoon in spring 2014. She is wearing a black robe and a long blue silk scarf hangs down from her shoulders. She welcomes me with the warmth of a mother and sits down beside me. Her eyes start glowing when she begins talking about her youth.

‘The organizer’s nonchalance allowed me stroll inside the Olympic Village, even though I was not supposed to do so. Later it was this goodwill the terrorists abused’, she remembers.

She talks about the autumn of 1972. The moment when the ideal of the peaceful games collapsed and the events were overshadowed by the kidnapping and killing of eleven Israeli athletes by Palestinian terrorists inside the Olympic Village.

‘Aicher was personally offended by this. It was the worst that could have happened. Several months later, when we started working in Rotis he still suffered from it. His zest for life, his humour were gone for a long time.’

So Rotis had to start off with a setback. With the first big jobs and the arrival of Aicher’s family and the installation of a fully equipped printery in the old shed, things moved on. Monika Maus became Aicher’s personal assistant and was mainly occupied with the redesign of Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen – the second German TV channel.

‘Aicher told the directors: “Look, if you always position yourself as second, you will never gain respect. Emancipate yourself, use the shortcut. From now on you are ZDF!”, and they went for it.’

He unified the studio layouts and backgrounds. He drew an alteration of the typeface Univers – with rounded edges – since the monitors at that time were not able to screen clear edges anyway.

‘The clock that the ZDF used for at least ten years – that was my clock. I was the only one in Rotis able to construct it properly’ says Monika Maus, ‘technisch korrekt.’

Even though her job was badly paid and the working hours were demanding, she enjoyed working in the studio. It was the parties, the exchange that came along with the many visitors and through the other young assistants, the ICE train rides to ZDF in Mainz, the exaggerated business dinners and not to forget Aicher’s strong personality that made up for it.

‘I admired his view on design. Also his sense of order; I was chaotic enough myself.’

She remembers how Aicher hated it when she was late for work, often because she had been stuck behind the slow milk truck on the unpaved road. Or how she had to repark her green R4 if it wasn’t correctly in line with the other cars.

‘It’s ridiculous to think about it now. I mean, today nobody would stay for a minute in such a place’, she says. ‘Individuality did not yet exist. It wasn’t a bad thing to submit to a bigger idea. We’ve been proud being part of it.’

First, Monika Maus and the other employees had their lunch in a nearby pub. They would regularly return late and tired from digesting the local food. ‘Schnitzel and pot roast – that’s all they had to offer’, she remembers. Aicher figured that if he wanted to keep this office going he had to take this into his own hands. He employed a cook who daily served light vegetarian food – and this is no joke – at eight minutes past noon. He converted the historical arch basement of the old shed into his new canteen: Rotisserie.

It was possibly Aichers little neuroses that made Monika Maus leave Rotis in 1976, but more likely that she simply had to move on with her life, had other tasks waiting.

Aicher had a hard time letting go of assistants. Without them Rotis was a quiet solitary place. Especially for a man like Aicher who was supposedly more connected to the concept of work than the concept of family.

On a farewell note to Monika Maus and other colleagues who left in the same period he wrote: ‘The children of Israel leave the promised land.’

Monika Maus: the child of Isreal. Aicher’s world in Rotis: the promised land.

Read this essay by Marius Schwartz in it entirety in The Green Our Sheep Graze, published and designed by Mitko Mitkov, 1% of One Verlag, Hamburg.

See more of Marius Schwarz's work here and read Grafik's Talent profile about him.