The latest title from Occasional Papers gathers together the oddments of exhibitions past, providing a vital archive of graphic experimentation as well as a fascinating adjunct to art history.

For the eighteenth-century English writer and moralist Samuel Johnson (or Doctor, if you prefer) small tracts and “fugitive pieces” were the lifeblood of a literary culture too easily lost and a repository that he tried his utmost to tourniquet. He was also aware that this could only be an exercise in mitigation; these were, literally, the unbound – pamphlets, flyers, sheets, cuttings, scraps – and, as such, their confluence was perhaps unbindable. Of course ephemera is, by implication, fleeting. The word ephemeral derives from the Greek “ephēmeros”, which means lasting only one day. The dailyness, day-to-dayness or quotidian nature of ephemera is not its weakness but its source of vitality. These are the most dynamic of textual objects, responding to events in the moment of their becoming, oxygenating and enlivening a public as they pass from press to hand to gutter.

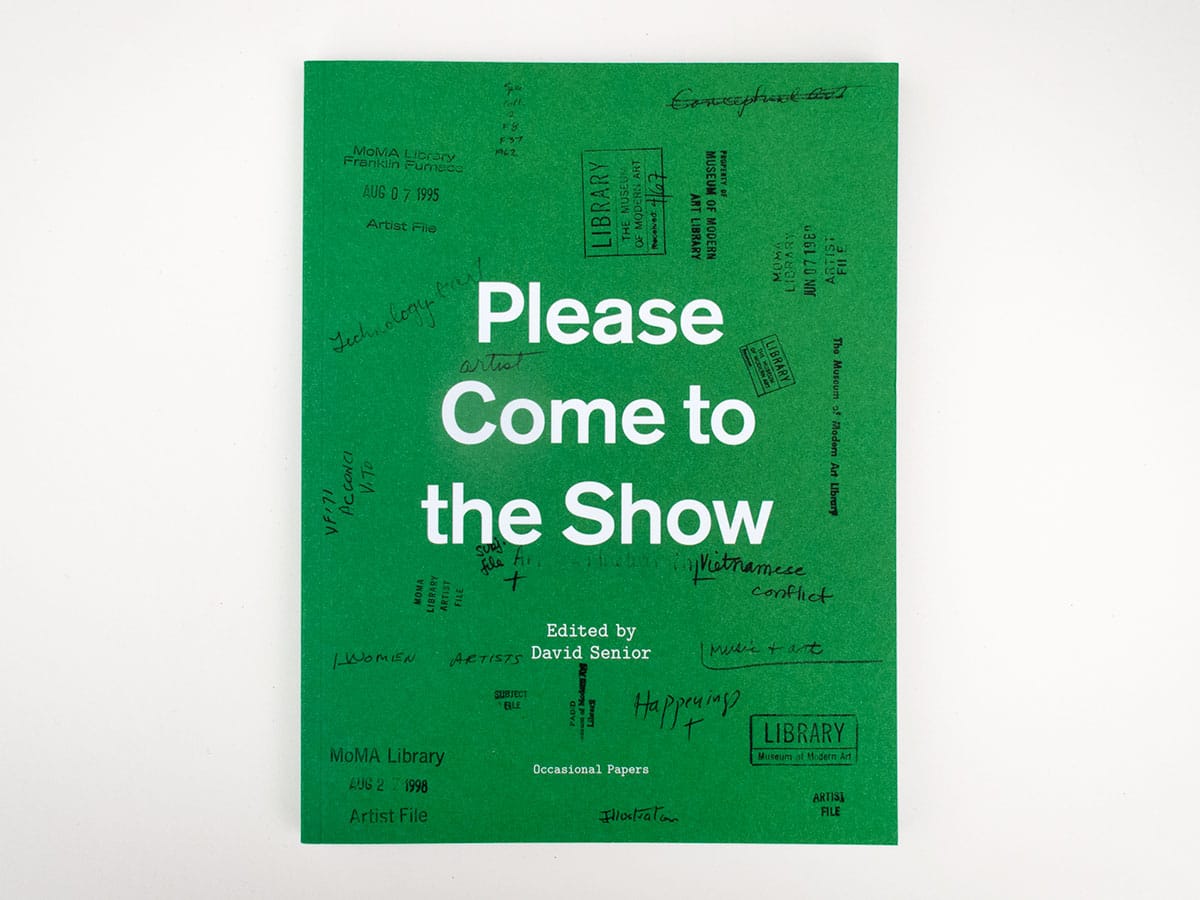

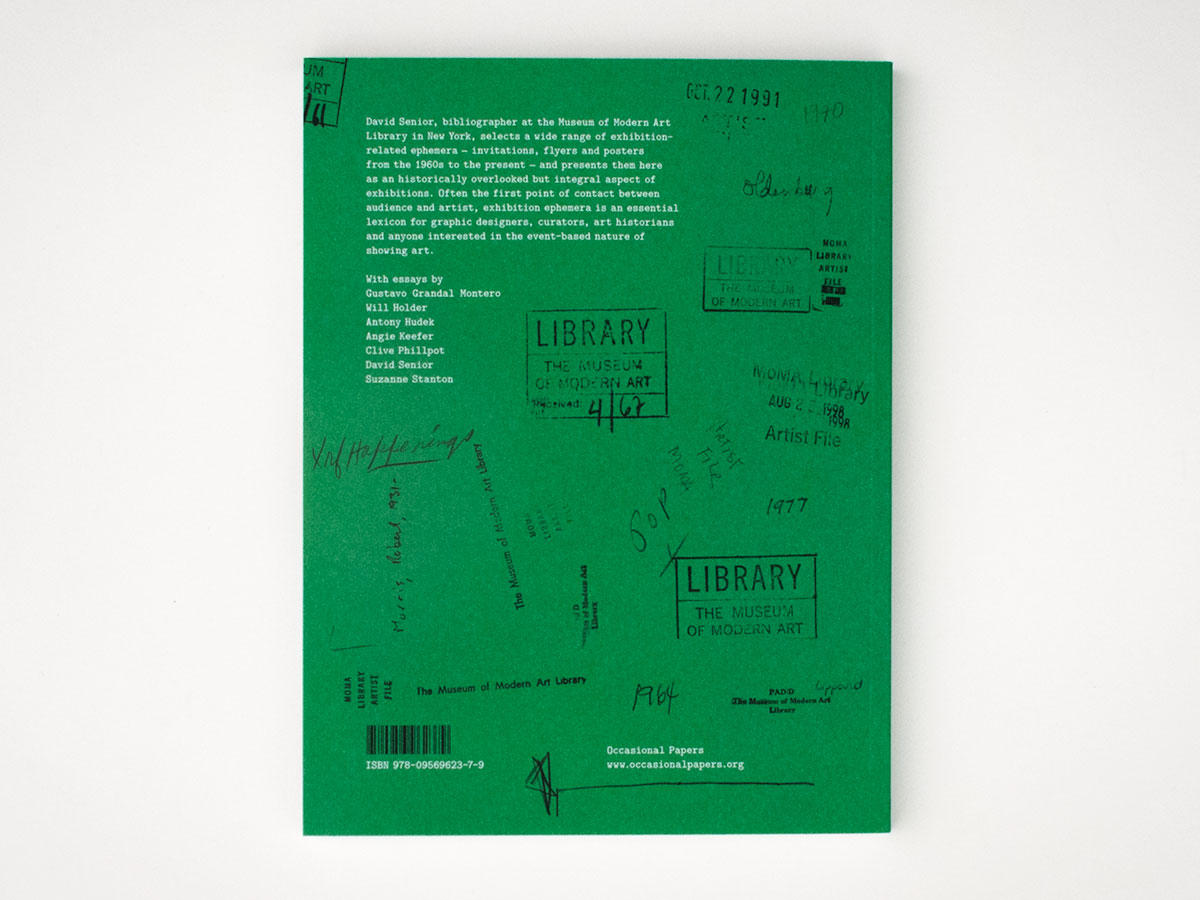

Digital technology has greatly accelerated the ephemeralisation of text and image; conversely, digitisation is also a process that produces no ephemera whatsoever – it does not deposit the sort of physical tokens that highlight their insubstantiality by, obtusely, hanging around. And while the majority might sit smugly in “paperless” offices and implore the rest of us to forget about the bumph, there remain arenas in which the decline of these small graphic gestures should and is being lamented. Evidence of this comes in the form of Occasional Papers’ latest publication, Please Come to the Show, produced to accompany an exhibition of artists’ invitations from the 1960’s to the present, which first opened at MoMA in 2013 before travelling to Liverpool earlier this year. At a time when the email press release and salutatory tweet are the main means of engagement, it is, as the introduction relates, a keen moment to reflect on the forms that these declarations of artistic intent have previously taken.

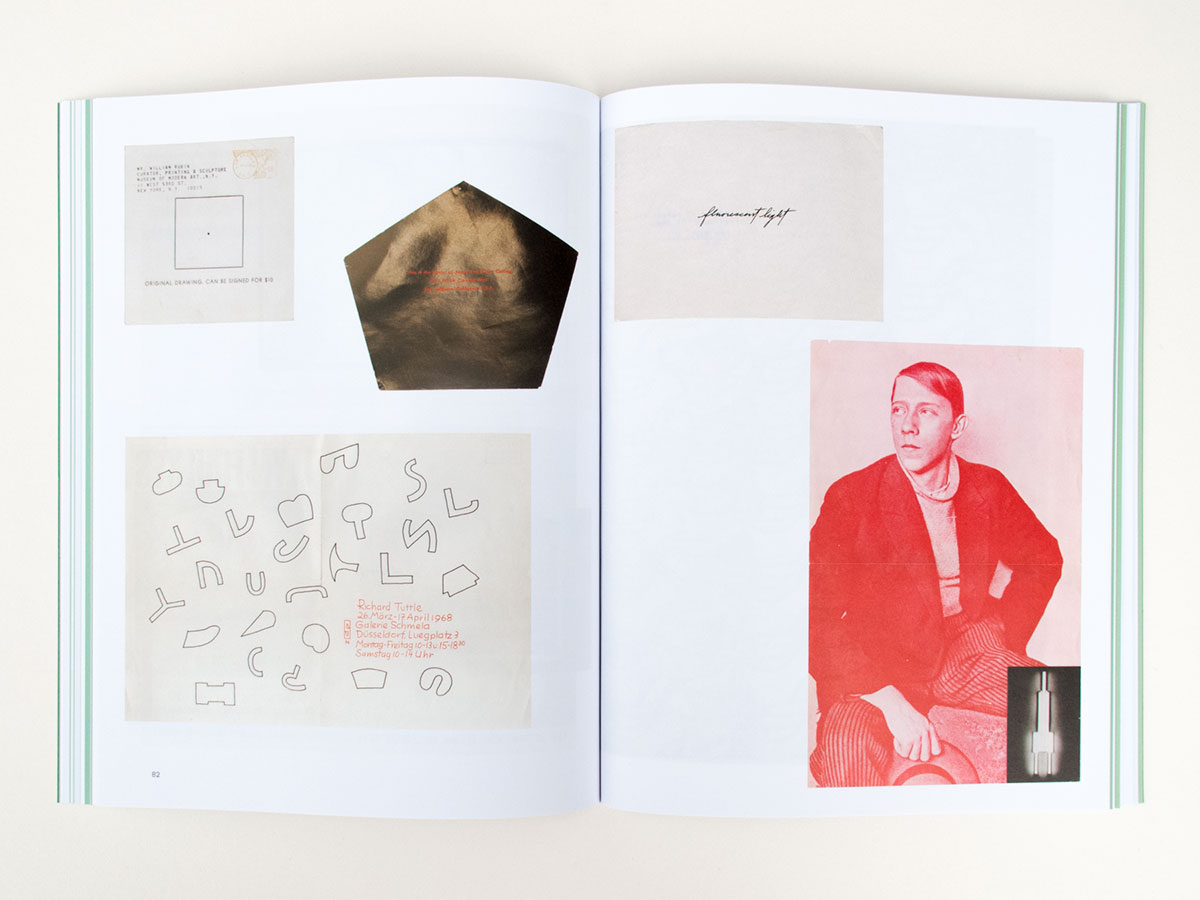

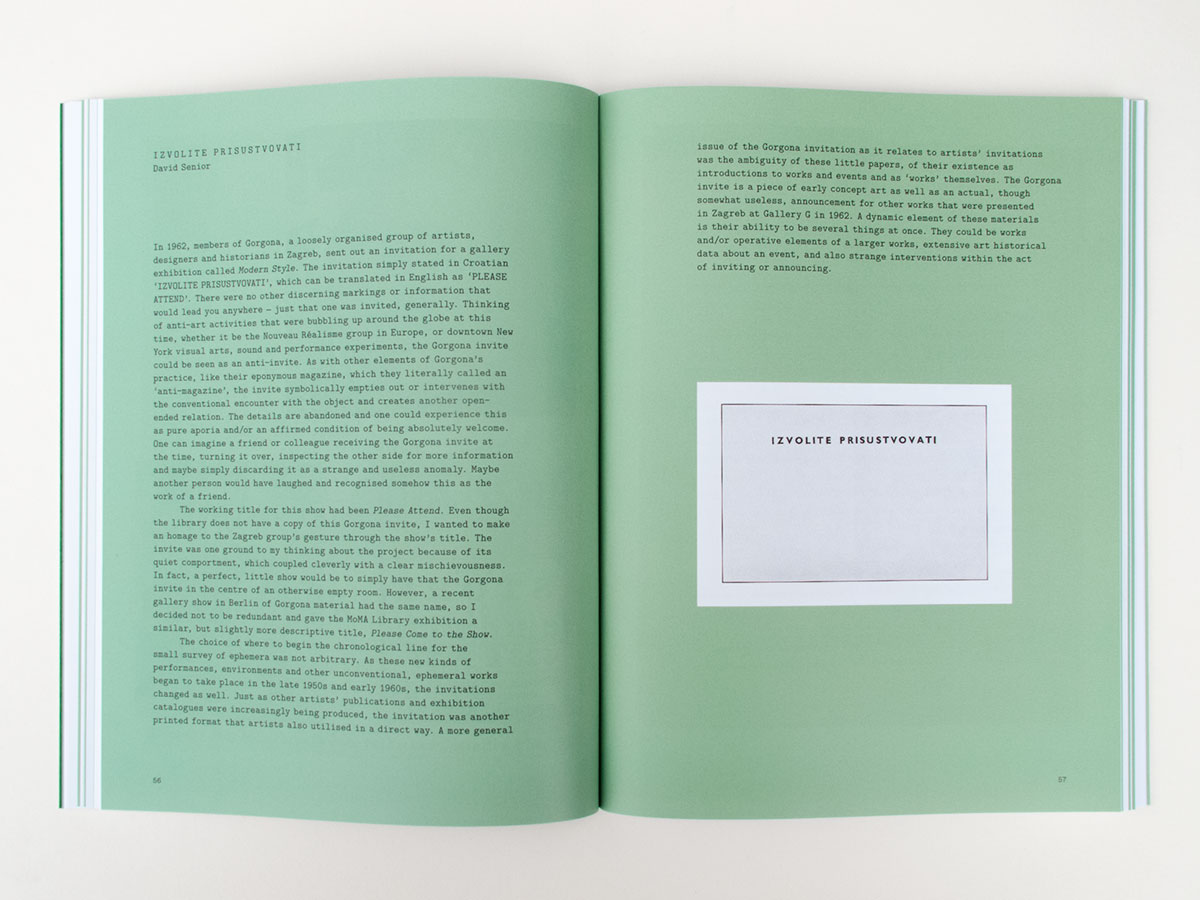

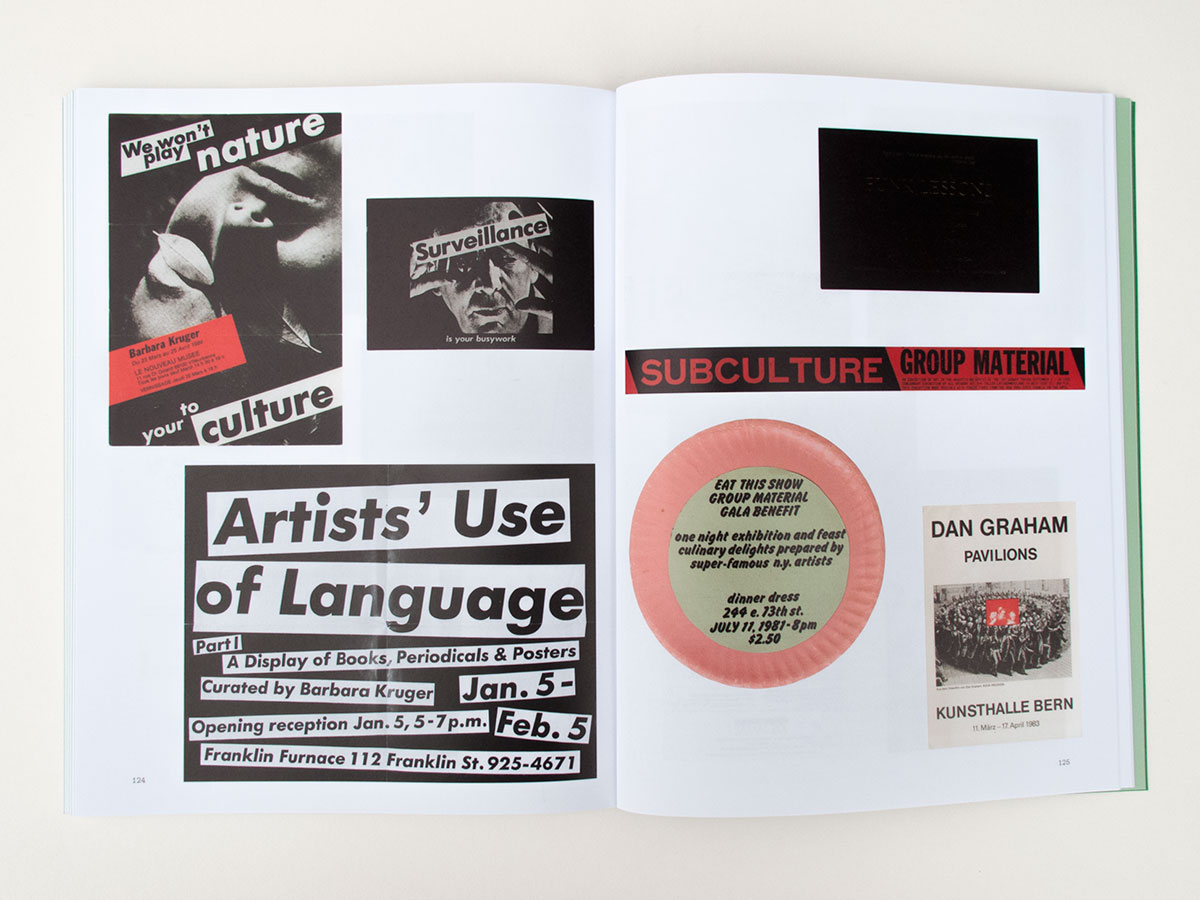

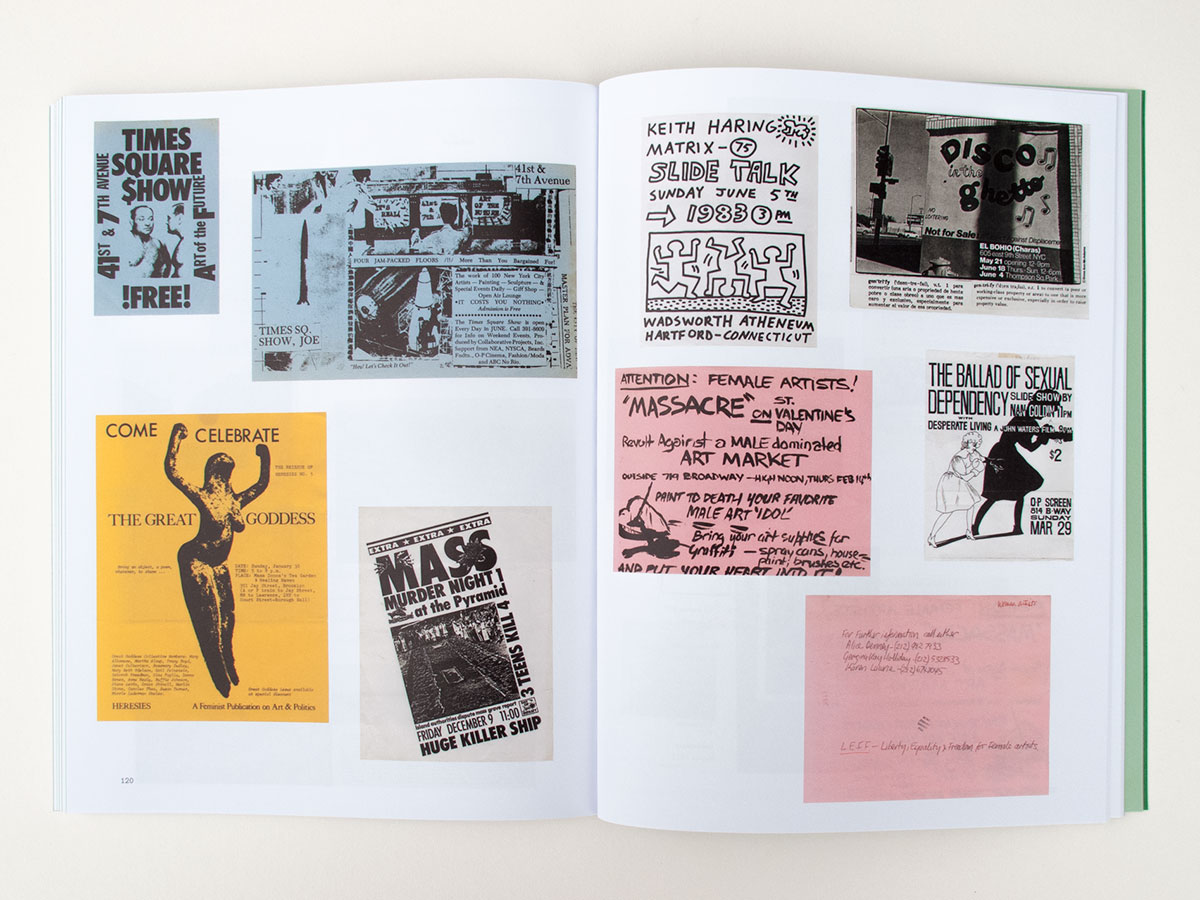

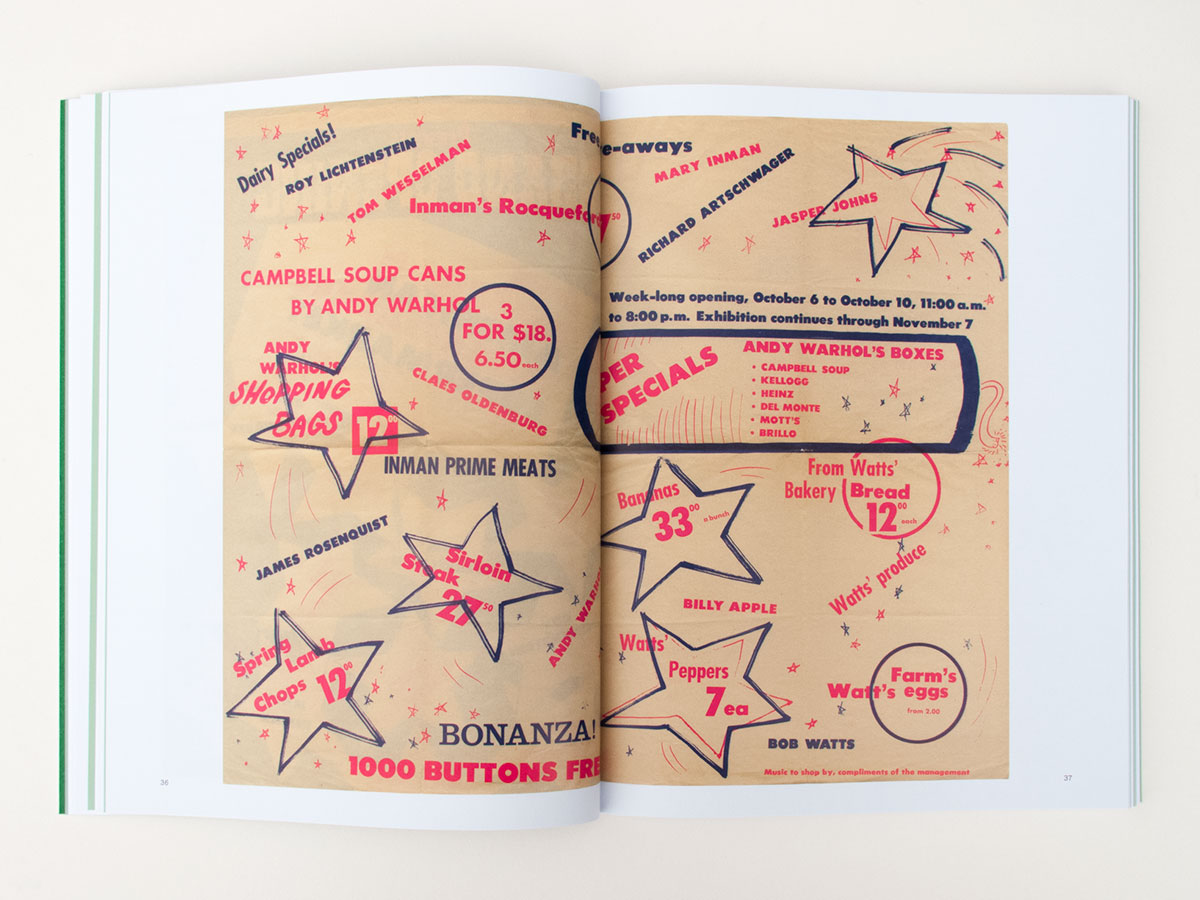

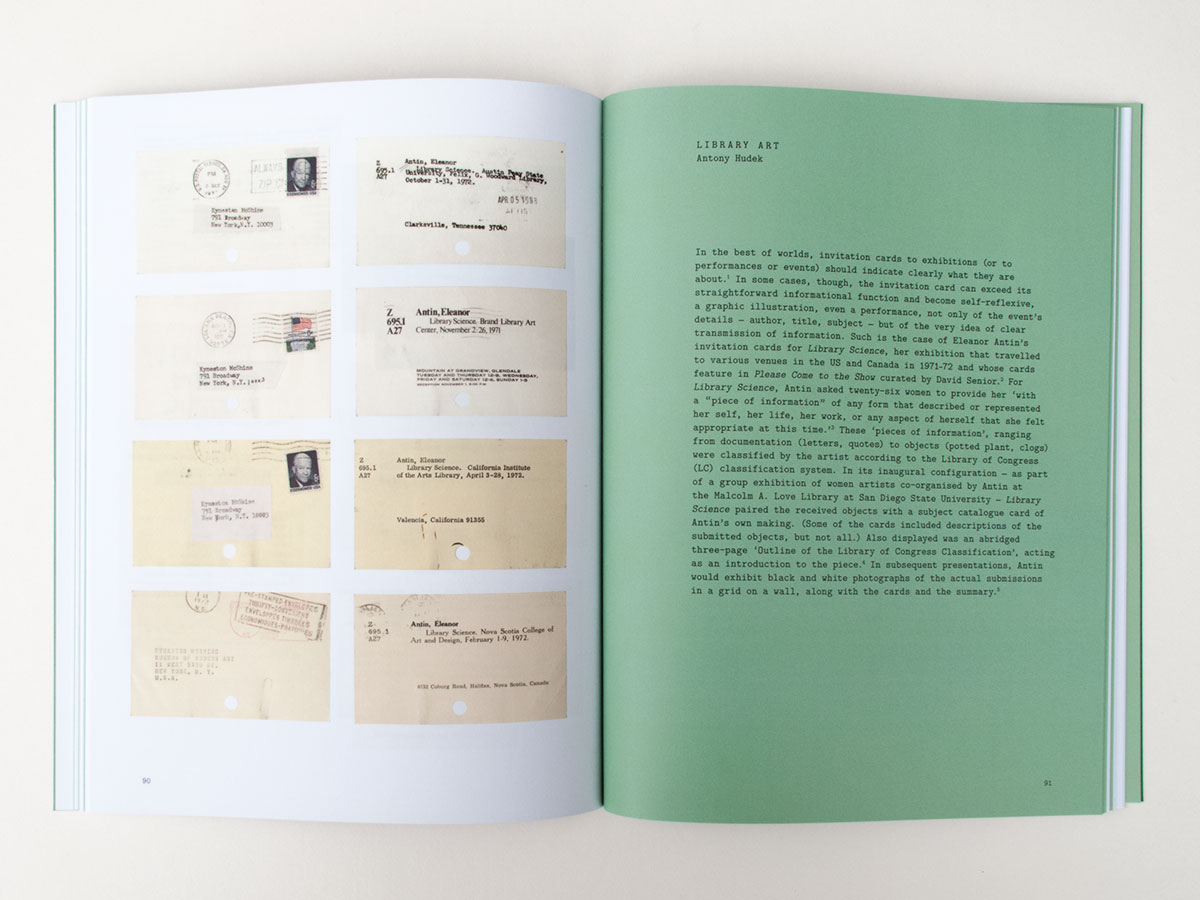

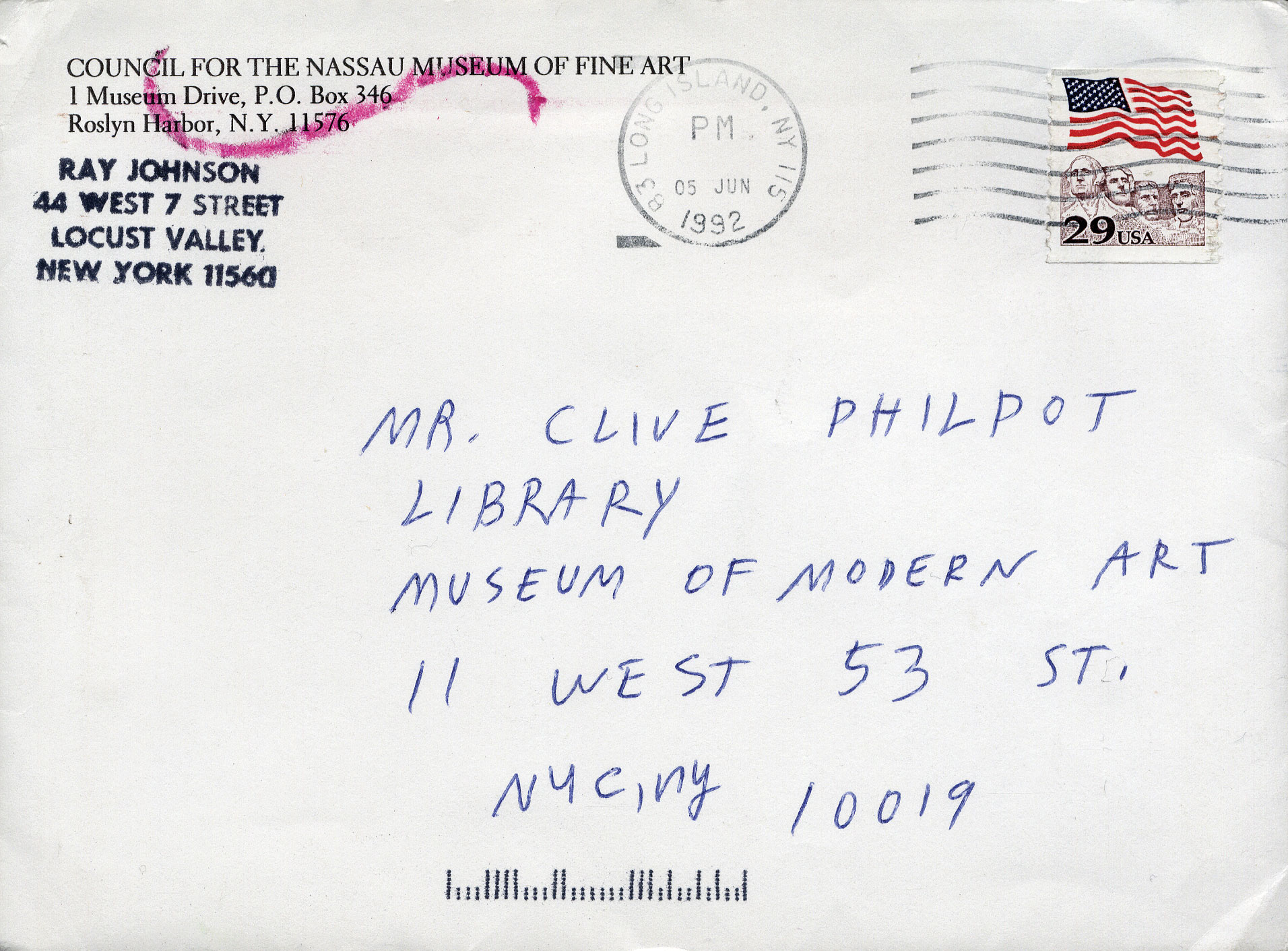

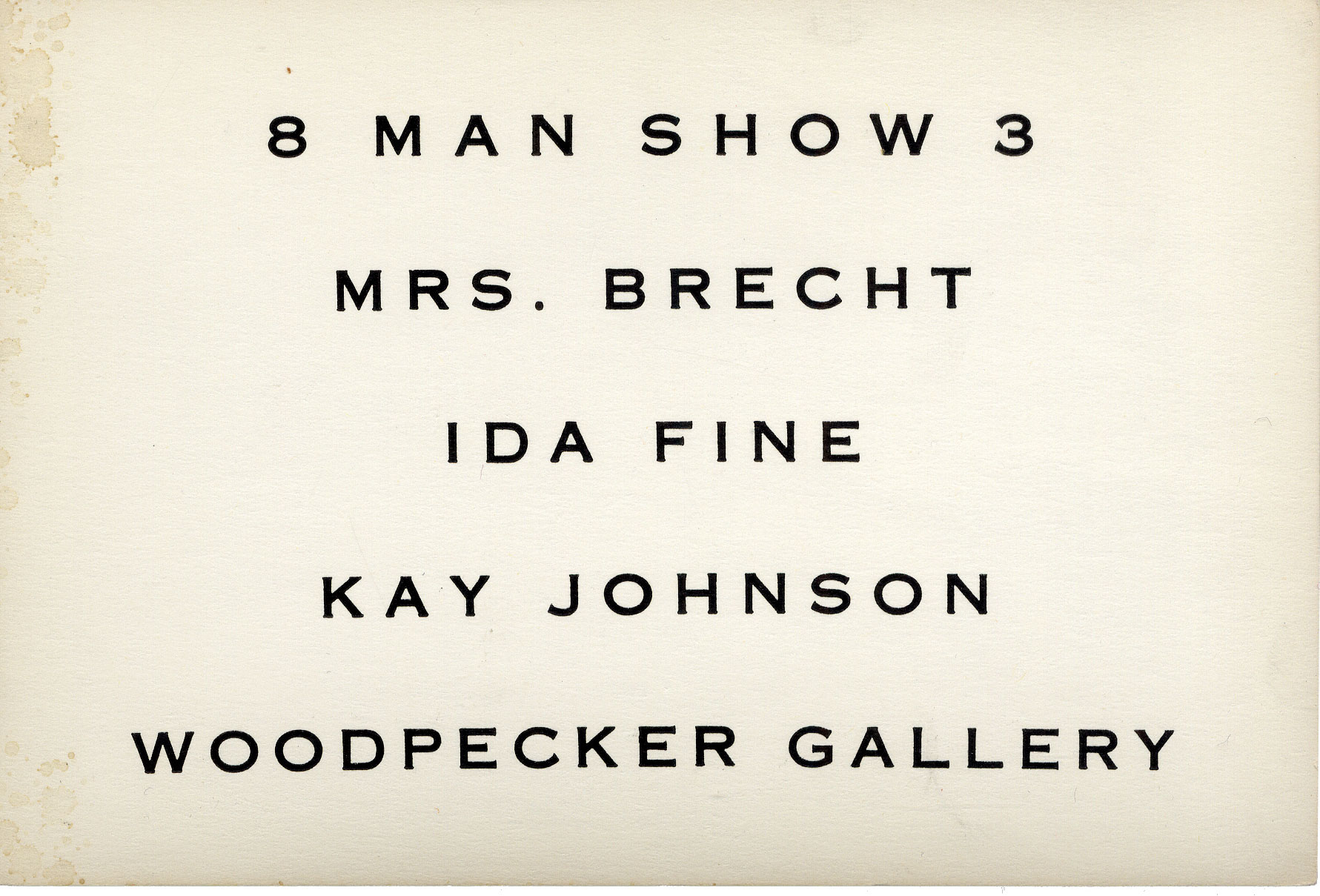

Edited by MoMA bibliographer David Senior, the title includes seven essays around the subject matter from the likes of Will Holder, Clive Phillpot and Suzanne Stanton. The majority of the spreads however, are given over to facsimiles of the invitations themselves. These are loosely arranged across luminescent pages of white coated stock, the images fitting where they will as if laid out across the top of a light box for inspection, not carefully composed and framed as if they were being re-postulated as artworks. As ever with titles in the Occasional Papers rostrum, the design steps out of the way of the (in this case visually combative) content without ever approaching anonymity. Matching clarity with personality is a considerable feat; this is a frank presentation of frank material. In one example Keith Haring invites us to his Slide Talk using an expectedly thick marker-line scrawl, his primal dancers cartwheeling across the belly of the paper; in another, Allan Kaprow entreats you “Dear Sir” to collaborate with him in a happening at the Reuben Gallery, the clipped language of the typed and signed letter a typical Fluxus send-up of officialdom; in yet another, what looks like a business card (scale is the one elusive determinant here) with a piece of gravel affixed to the front offers only mineralogy and art show metadata as enticements to Michelle Stuart’s 1980 exhibition in Lund.

Whether extrovert or demure, enticement is the crux of each example: these are at base a type of anticipatory device. As the artist Angie Keefer points out in her accompanying essay, there is an important frisson between the advertisement and the announcement here – artists (especially those of the 60s and 70s) are not adverse to manipulation, but its phraseology has to either fall away from the hawking of one’s self and work or ironically into bed with it. Where these two modes of advert and address diverge is in the announcement’s role as “a guide to what can be seen”; for Keefer each of these examples “trots ahead of the main event, but it issues from the same source.” There is nothing so ephemeral as the ghost of something that is yet to occur, let alone expire. By emanating from the same place they avoid being a shill for some exterior object, and by being ahead of time and out of context they swerve the overbearance of the exhibition itself: not artworks, then, but certainly art work. It is their position in that interstice between the hoarding and the gallery, the irreverent and the high-minded, that provides these articles with their fascination – the bravura of the salesman mixed with the recalcitrant genius of the artist marries into a graphic and literary style that is wonderfully pugnacious, and quite specific to this medium.

The events which these announcements presupposed have long passed and soon the era of their employment might be too – as such, Please Come to the Show is something of a reliquary for a form of design communication that offered a unique set of parameters and transgressions. These invitations are now fixed and defunct, no longer able to pick up the personal patina of doodle, dog-ear and smudge that they acquired in transit and that created, as Senior points out, an under-examined coda to art’s history. Nevertheless, to have them collated here means that the ideas they represent might remain in circulation a little while longer, invitations towards pursuing new venues for experimentation when and where we can.

Please Come to the Show

Ed. David Senior, 2014

Published by Occasional Papers, £17.50