Richard Hogg has been busy lately – as well as being an accomplished illustrator, he is now a fully-fledged videogame designer with a PS4 release under his belt. Anna Lisa Reynolds went to meet him at his seaside studio, and discovered the enchanting world of Hohokum.

It’s a sunny Friday afternoon in late summer and I’m sitting in a dark room in a house in Hastings, blinds drawn, glued to the Playstation. I’ve got a sneaking, skiving-off feeling - wasn’t there something less fun I was supposed to do today that, thanks to this game, I’ve now forgotten about? But gaming is, in part, why I’m here – the room in question is Richard Hogg’s studio, and I’m playing Hohokum, the game he’s been working on since 2008 and, as part of a small team of collaborators, has developed from a single-level demo to the full, publically-released Playstation game I’m messing around with today.

Bringing the game to this point has clearly been an intense process for Hogg, who branched out into videogame design from an already established career as a graphic artist and designer. He started out at Airside, in a job he entered into as, in his own words, “a bitter, failed fine-artist in my late twenties.” The job would prove instrumental, cementing the playful approach visible in his work even before videogames entered the mix. He eventually left Airside to set up independently, balancing self-initiated projects with commissions spanning editorial illustration, ad campaigns, identities and animations, for a client list including the Design Museum, O2, Barclays, the BBC, and Wired magazine. Grafik itself was on that roster, too - readers of the printed mag might remember Hogg’s illustrations for Nat Hunter’s How to be Green column in 2010.

The segue into videogames came through his friendship with Ricky Haggett, founder of the indie games developer Honeyslug. They’d spent years talking about creating a game together – Hogg doing the visuals, Haggett the build - and started playing around with ideas in their spare time for how Hogg’s drawings might form the basis of a playable environment. It was out of these early doodles that Hohokum emerged, though their first collaboration to come to fruition was Poto and Cabenga an iPhone based side-scroller. Developed for a competition at the Game Developers Conference in California in 2010, it was chosen as one of six finalists from over 150 submissions. Hogg and Haggett were spurred on, and work on Hohokum continued in earnest.

Last time I caught up with Hogg back in 2011, a demo version of Hohokum had just been unveiled at the Independent Games Festival in California. Keen to to take it further, he and Haggett were in need of a backer. That support came in the end from Sony’s Santa Monica Studio, who they first encountered through a different videogame commission, Frobisher Says, for the launch of the Playstation Vita. Hogg and Haggett were initially wary that their game would be steered in a more mainstream direction, but found themselves pleasantly surprised by the Studio’s attitude in that respect. “It was mainly the more videogame-y ideas that got thrown out,” Hogg recalls. “Hohokum’s less like a normal videogame than we thought it was going to be, and Sony Santa Monica were very supportive of that - they encouraged us to embrace the weird and less conventional stuff, and we realised that was our strength.”

With the studio’s support, the team working on the game grew to a fluctuating group of between twelve and twenty programmers, animators, project managers and gaming experts – a far cry from the days when it was just the two of them, but still a comparatively small team in the world of videogames. “I think we made this game with about as few people as you can get away with,” says Hogg. His own role was as both visual artist and art director, drawing and refining the game’s environment and inhabitants and working closely within the team to bring it all to life.

Creating that first demo level had left Hogg and Haggett with plenty of ideas for how Hohokum might turn out on a grander scale, but that soon changed. Once work on the full game had begun in earnest, experimentation and trial and error underpinned their approach. “We worked on Hohokum in a very emergent, ad-hoc way, not really planning anything, and throwing away lots of our existing ideas,” he explains. “I think we managed to maintain that approach throughout the process – we were still playing around with it and adding in silly little details right up to the point when it launched.”

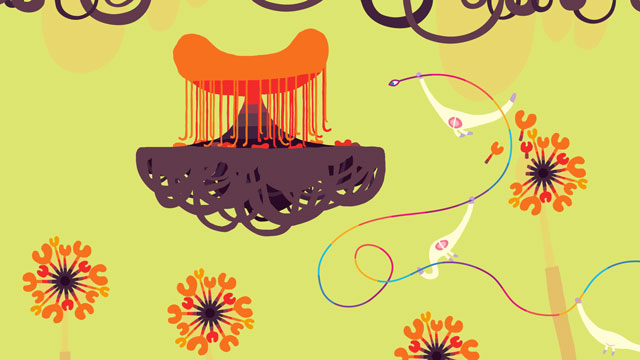

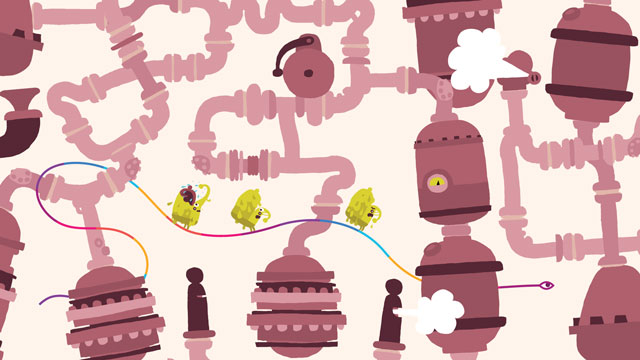

Playing around is a fair description of what Hohokum itself entails. Taking control of a snake-like creature called the Long Mover, you navigate a series of interactive worlds, interspersed with creatures and characters to interact with, assist or annoy. It’s more an environment to explore and tinker with than a traditional, videogame-like set of problems to solve and stuff to unlock; you’re not supposed to kill anything or collect keystones or beat the boss, you don’t have lives, and there’s no tiny stopwatch counting down in the top corner of the screen. It’s just a very pleasing place to experiment with, to just to be – bouncing off things to see what happens when you do, and zooming around really fast. You can even make a mess, if you want to. There’s a subtle hide-and-seek narrative within it, just prominent enough to be discernible if you’re looking for it, but easy enough to ignore if you’re not. Mainly, as I discover, it’s enough of an immersive pleasure just to be darting around this richly detailed world, all bearing the hallmark of Hogg’s distinctive, slightly wonky vector style. It’s charming, and addictive – two hours of play pass and I’ve barely noticed.

Talking to Hogg as I’m playing, I point out how enjoyable it is to find something so free from the expected conventions of a console game. It seems the welcome lack of familiar gaming tropes within Hohokum has puzzled several reviewers so far – not that the positive write-ups have been scarce. “One of the most common responses, which I really like, is that people say ‘I don’t know what the fuck’s going on here, but I really like it’”, he adds.

Nevertheless, the reviewing process sounds nerve-wracking, and not something he’d ever had to endure in the other side of his career. “Reviews don’t really happen to graphic designers,” he explains. “You don’t really get any kind of critical input most of the time. I’ve felt quite exposed since the launch, actually, because the videogame community is very quick to judge - either a game is amazing or it’s shit. And that can really hurt people actually, or on the other side of it, really inflate people’s egos.”

Speaking to Hogg about how the game has been received, it’s clear just how much of himself he’s put into it. Indeed, you can see hints of Hohokum scattered throughout the rest of his portfolio – not necessarily in the visual style of the work, but in the way that much of it shows a snapshot of what seem like fully realised, fantastical other worlds. The slightly bittersweet, occasionally dark edge that runs through it is there too, as a counter to the jolly riot of colour and bouncy, cartoonish cast of characters. Just as in the rest of his work, there are moments of sadness and wistfulness in Hohokum that take the edge off, so to speak. That, too, is completely intentional: “Some of my favourite parts of the game are ones that are a little bit sad, or depressing, almost,” he tells me.

I’m interested to hear how working on videogames has affected Hogg’s approach to his other work. “Sometimes it’s hard to take the crazy deadlines seriously,” he admits. “For example, I love working with advertising agencies and the people that live in them, but the way they work can be quite frantic. It’s really weird coming back into that from a world of videogame people, where everyone tends to be more organised and pragmatic. They’re used to working to six-month milestones, that kind of thing, so it’s hard to take the headless-chicken approach seriously when you’ve been working on a game for two years. It makes you realise that a lot of the crises about deadlines and all that are nonsense – even if it’s nice nonsense, and I quite like it.”

There have to be a few manic moments, I suggest, when you’re in the thick of it and the game’s release date is mere weeks away? “When you’re working on a videogame, the crisis is more centred around this thing or other not working, and videogame people are very relaxed about it,” he says. “It’s a world of absolutes, because they know from experience that if you approach the problem logically, you will find the thing that’s broken, and you will be able to fix it. I’m really enjoying the contrast between that and the slightly tinseltown feel of ad agencies at the moment.”

Hogg has continued to work on other projects intermittently whilst Hohokum was in development, and now it’s been released he’s enjoying the different pace of commissions outside the videogame world, although there might be more games in the pipeline. “Ricky and I have got some strong ideas for another game and we’ve learned a lot from the process of making this. One thing we learned in particular was the value of really good animation, and we think we can do some really good stuff with that. In Hohokum, you’re whizzing around and it’s easy to miss stuff, which is a shame when you’ve got really strong, almost old-fashioned animation that you don’t see so much in videogames. We like the idea of a game where the pacing and the way you move around it allows the animation more time to shine.”

The idea of a direct follow-up to Hohokum holds limited appeal for the pair: “We’re definitely not making any more Hohokum,” Hogg asserts. Still, in the short time it’s been in the public realm the game has already spawned a storybook, a soundtrack vinyl LP from record label Ghostly International (which also makes for pretty good music to write to, I discover), and also inspired players to come up with their own fan art, Hohokum maps and even a kite version of the long mover. It’s developing a life of its own, and engaging its players in a way that’s surely very satisfying for its creators, after their labour of love.

Hogg says he’s not really got any idea of the Hohokum’s sales so far, and I can’t blame him for not looking too closely – aside from the obvious commercial interest, it doesn’t seem the most reliable yardstick for a game’s success. It’s hard to say whether Hohokum’s slightly off-the-wall and abstract character will result in a sales smash or a sleeper hit, but I leave that afternoon with a hope that plenty of people try it out, gamers or not. As for me, as I make my way home I notice an extravagantly-sized blister on my thumb from the joypad, something I’ve not had from gaming for a very long time – high praise indeed.