A customarily huge book on Le Corb that is not actually meant to be read? Jonathan P Watts battles arm-fatigue to give us a blow-by-blow account of the latest addition to the heaving Le Corbusier canon.

“In architecture,” Le Corbusier famously wrote, “there is no such thing as detail, everything is important.” Just as well for the Corbusier publishing syndicate, which of recent seems to be attempting to fulfill the logic of this statement by producing books on the Modern Scion and, well, just about everything.

At least eight monographs have been published on Père Corbusier in the last eighteen months, four times the number of those published on Mies van der Rohe. In March and then April this year, two books addressed exactly the same subject — his churches — which must have been the cause of much chagrin for all involved. You’d probably get two nights board in Le Corbusier’s Unité d'Habitation for less than the cost of buying half the books published on him in the last eighteen months.

[M]achine age urbanism and building were rolled out into environments irrespective of people’s needs or sensitivity to place. Le Corbusier: An Atlas of Modern Landscapes, edited by Jean-Louis Cohen, Professor in the History of Architecture at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts, follows hot on the heels (or spine) of his book Le Corbusier’s Secret Laboratory: From Painting to Architecture, published this Spring. So what makes thispublication so necessary?

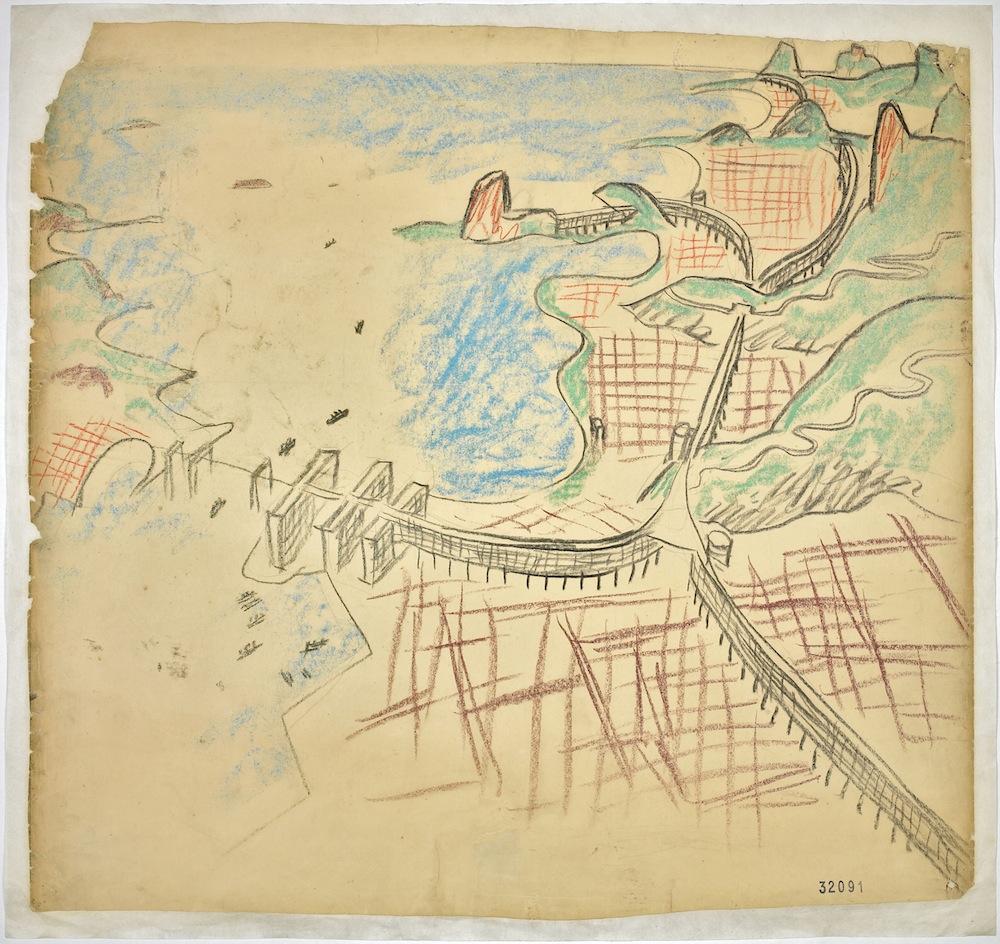

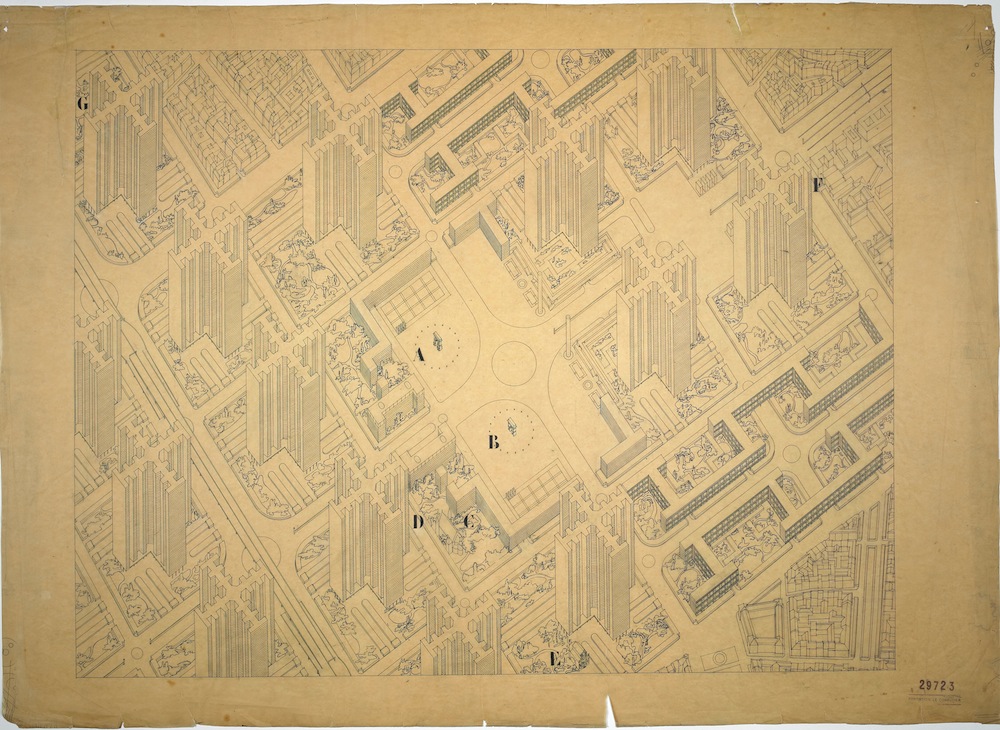

The book accompanies a major exhibition of the same title at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, that addresses a lack: “If there is a blind spot in the astonishingly vast literature dedicated to Le Corbusier,” Cohen’s opening essay begins, “it is certainly his relationship to landscape”. This, despite at least two of his five points of architecture seeming to address the topic — the pilotis, reinforced concrete stilts that lifted housing blocks off the ground, thus freeing land surface beneath, and also providing private domestic roof gardens. To this we can add the horizontal window, which Beatriz Colomina has so convincingly argued rendered many of Le Corbusier’s houses not simply machines for living in, but also — with the unmitigated complexity of the former oft- quoted aphorism — machines for viewing landscape.

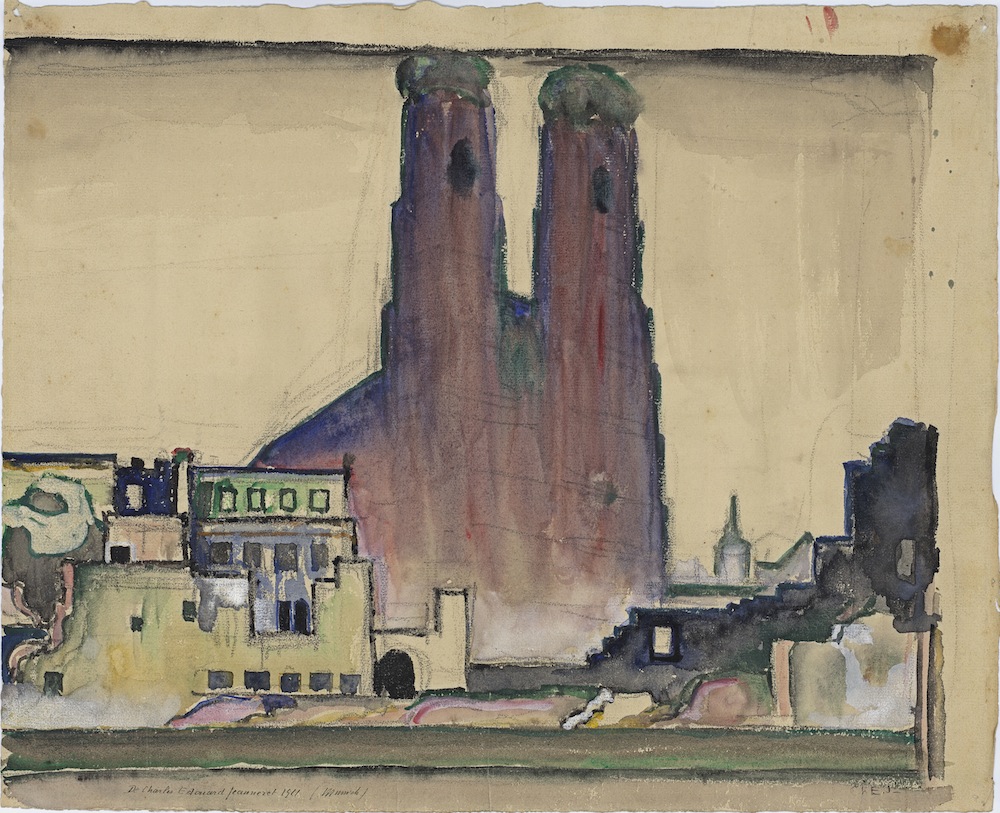

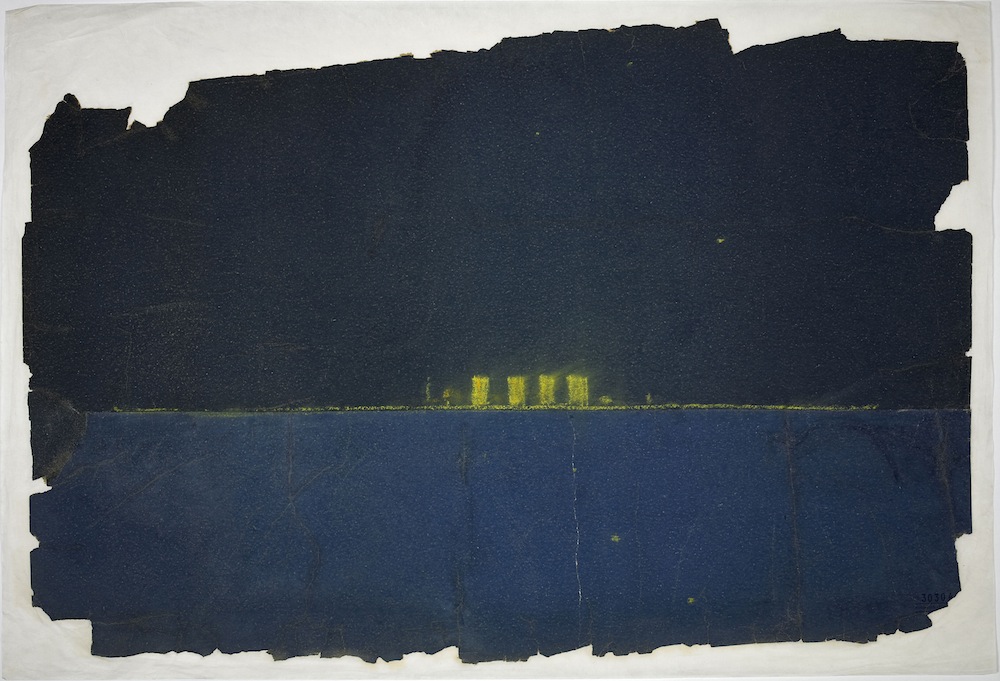

However, Le Corbusier’s pilotis (as Martin Pawley once observed), lift housing blocks off the ground, thus destroying their relationship with the earth. And machine age urbanism and building were rolled out into environments irrespective of people’s needs or sensitivity to place. “The city,” he wrote “is man’s grip upon nature. It is a human operation directed against nature.” Architecture should stand in contrast to nature, rather than appear as an organic outgrowth. In the 30s Le Corbusier changed his mind about the inevitably beneficent workings of a machine-age civilization, moving towards what Kenneth Frampton calls a “monumental vernacular”, of which the pilgrimage chapel at Ronchamp is exemplary. It wasn’t until the early sixteenth century...that landscape, as we call it today, began to gain traction as a an aesthetic category. “The relationship of building to landscape is manifest in some of his work,” Cohen assents, “but in a large portion of his production it is latent, not the central focus of the project.” One of the problems is the nebulousness of the term ‘landscape’. Cohen offers a working definition via philosopher Alain Roger who argues in Short treatise on landscape (1997) that it denotes both the physical and visible form of a specific outdoor space, and its graphic, pictorial or photographic representation. There is, according to Roger, an intimate relation between the two, which he calls artialisation. Physical and visible landscape and representation of landscapes are in mutualistic relation, they inform one another, constantly refashioning ideas of landscape. In fact, Roger argues that an idea of landscape as a physical and visible space was impossible without its representation. It wasn’t until the early sixteenth century, when views of land began to be valued in their own right, that landscape, as we call it today, began to gain traction as a an aesthetic category.

Of course Le Corbusier was an avid painter, photographer and cinematographer. One problem with Roger’s working definition of landscape, however, is that it slips into ocularcentrism — it is dominated by vision — which is rendered all the more confusing when terms such as “nature”, “garden”, “plan” and “site” are used as synonyms of landscape.

In light of this blindspot, the purpose of this book is to set a new agenda for the study of Le Corbusier. Cohen’s opening essay really does set an exciting agenda, however many of the other essays are simply encounters or miniature case studies on specific buildings. They take for granted working definitions of landscape, advocating relational, multi-sensory approaches that, arguably, are a corrective to Roger’s ocularcentic definition of landscape.

An Atlas of Modern Landscapes opens directly into an exquisite photo essay by Richard Pare of Le Corbusier’s buildings. (Late last year Pare’s photographs of neglected Constructivist architecture were central to the brilliant exhibition Building the Revolution: Soviet Art and Architecture 1915-1935 at the Royal Academy, London.) Photographs spread across the centrefold and a double fold-out page show beguiling panoramas of Chandigarh and Ronchamp. After this, there are many fascinating smaller photographs by Pare and archival images courtesy of Foundation Le Corbusier, but none so big as those at the beginning. The following four hundred pages are text and footnote heavy, and the page margins are extraordinarily wide. I’m not a design philistine; my copy for this review was almost late because I could only manage ten minute reading stints in bed before going weak in the arms. Why commission top rate academic essays for such a great lump? Make it an exquisite photobook or a smaller, focussed collection of essays giving an historiography and contemporary takes on “landscape”, “nature”, “garden”, “plan” and “site” and Le Corbusier’s work, with a functioning index. Or maybe this is a book that is not supposed to be read?

The latter would be fascinating because Corby had a contentious, often contradictory, relation to these things. An Atlas of Modern Landscapesis too keen to retroactively fit Le Corbusier to landscape. Whatever your preferred moniker for the architect, Saint Corbu doesn’t need any more hagiographies. And book sales are unlikely to be affected. Le Corbusier: An Atlas of Modern Landscapes, ed. Jean-Louis Cohen

Published by MoMA, £49.95