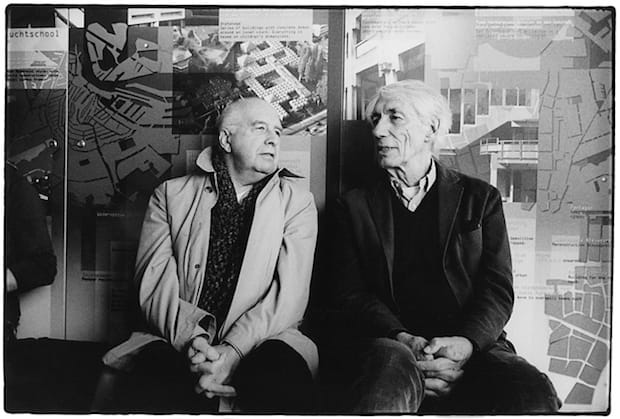

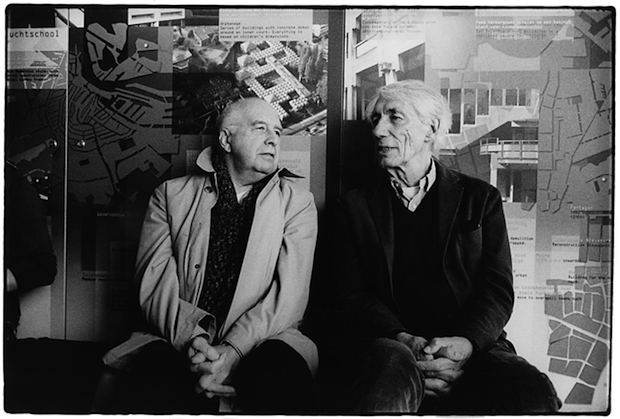

In 1972 Wim Crouwel and Jan van Toorn shook up the design world when they went head to head on the purpose of design. With the transcript now published in English, Emma Tucker reflects on this colourful debate with its two iconic protagonists.

In 1972 design history was made in Amsterdam, when Wim Crouwel and Jan van Toorn took part in a impassioned debate at the Museum Fodor, each arguing for their own strongly-held opinion on how objective, or not, a designer's role needed to be. Crouwel called for the designer as a neutral conduit through which communication should pass; while van Toorn saw the designer as an intermediary who must, by their very nature, intervene.

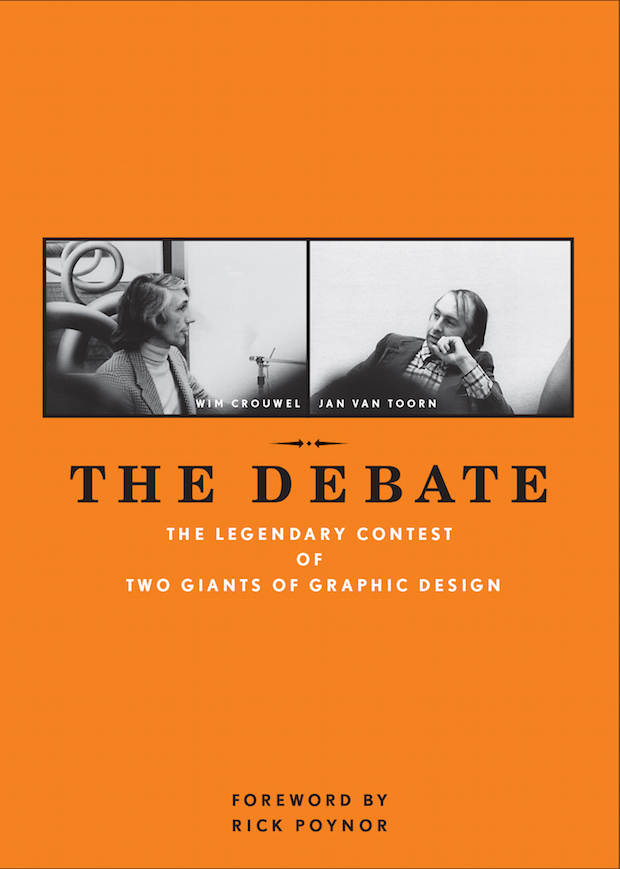

Although significant, it's a piece of history that was little-known to English speakers until now, and The Debate, published by Monacelli Press, marks the first English translation. Indeed it's only in recent years that the discussion has been published at all, and until the recovery of the recording by curator Dingenus van de Vrie in the early 2000s, the debate existed only in people's memories, and as a few fragments published as part of a monograph on Total Design – the studio co-founded by Crouwel in the early 60s. There's something tantalising about seeing finally set in words something that, for decades, had remained a matter of 'folklore', as Rick Poynor terms it in the book's introduction.

Poynor also flags the event as a rare example of two key figures in the design industry taking each other on, vehemently and in public. It's a demonstration of two individuals absolutely refusing to compromise on their opinions; something that runs counter to today's feeling of willing acceptance. “Pluralism,” Poynor states, “a willingness to accept that there are plenty of ways of doing design, or anything else, and many equally valid outcomes, has become our constitutional preference.” He makes a good point, and these kinds of debates between significant design figures are few and far between. Max Bill and Jan Tschichold took each other on in the 40s, when Bill accused Tschichold's New Typography of being “an unacceptable retreat into convention”, while at the end of the 80s Tibor Kalman and Joe Duffy also found themselves at loggerheads over whether design had become too commercialised. There's something thrilling about the thought of two juggernauts of design battling it out, in public. Imagining what might be today's comparisons – Spiekermann versus Sagmeister, Bierut vs Brody – it's hard to believe there would be either the platform for this to take place, or the willingness to take part.

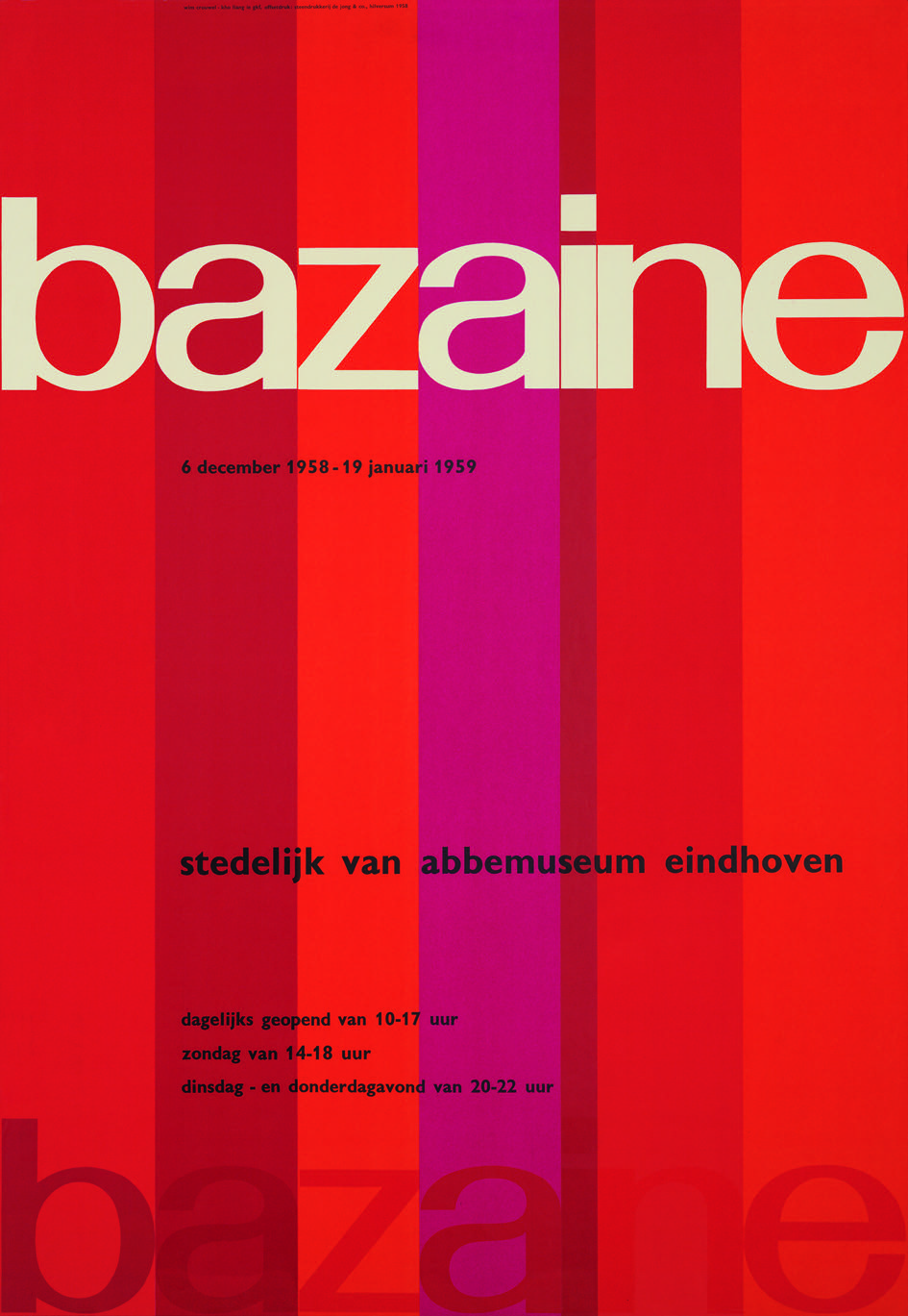

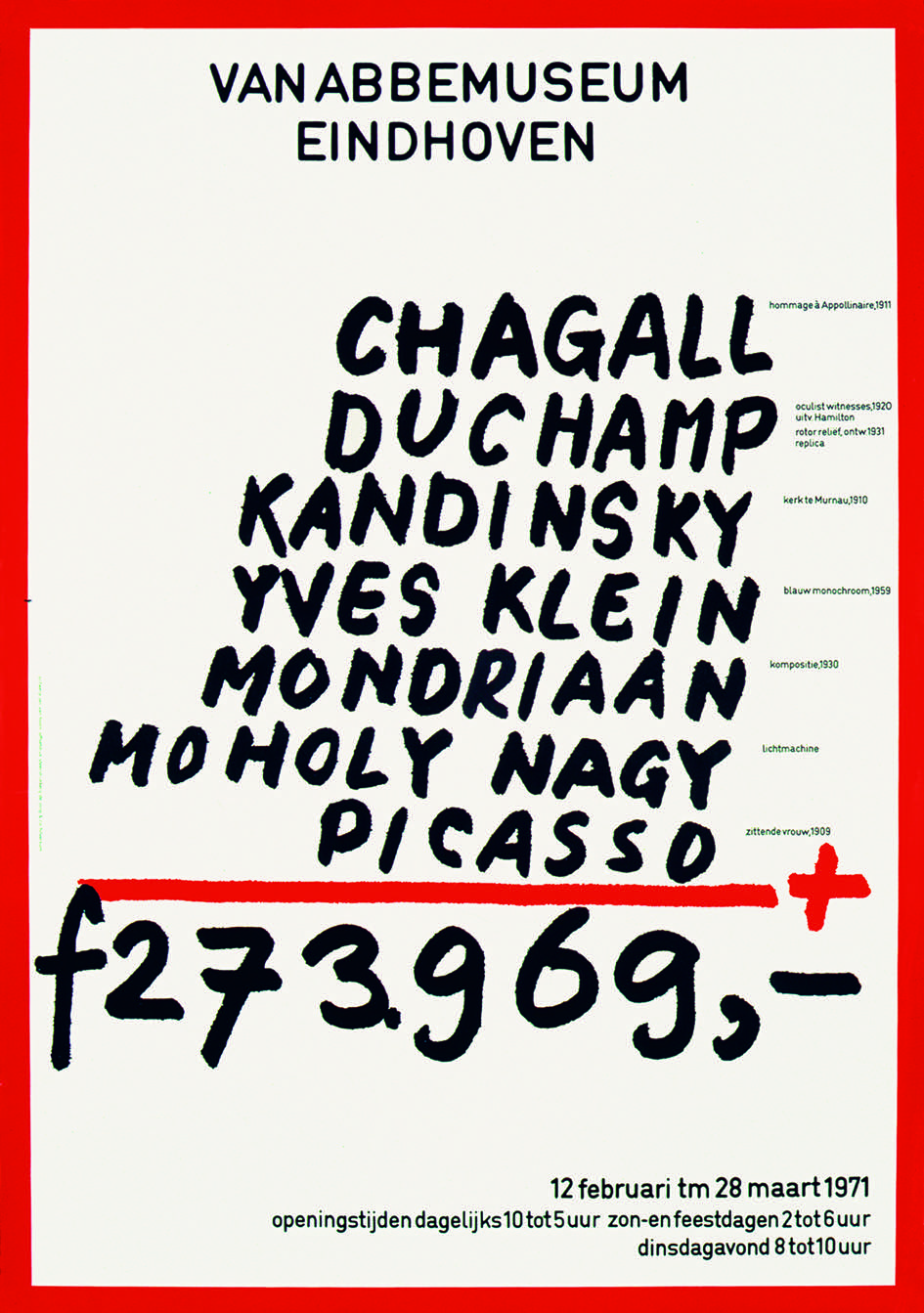

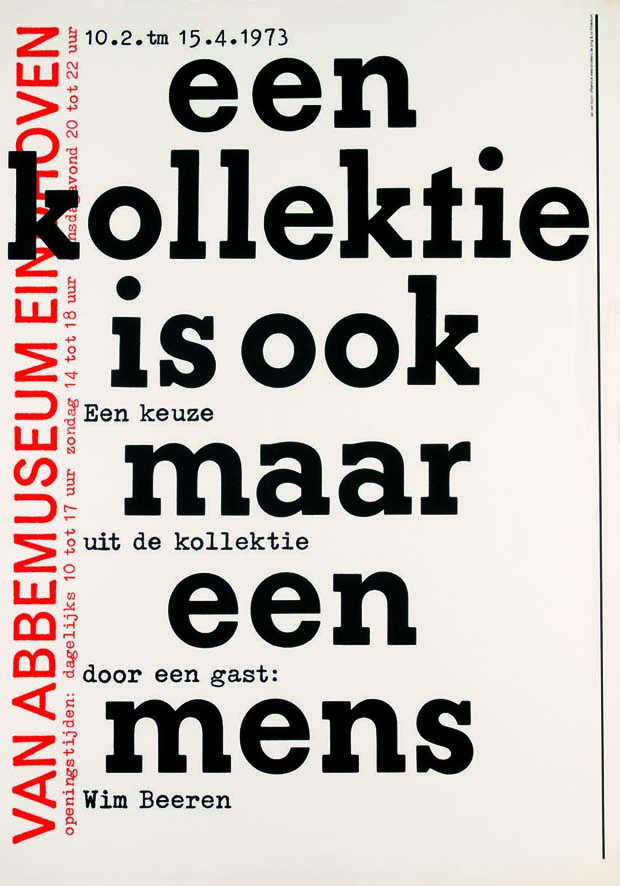

The van Toorn/Crouwel debate came after a time of unrest for the Dutch design industry, and in her essay in the book historian Frederike Huygen notes that it had spent much of the 60s preoccupied with changes, and a developing polarity between the world of art and designer, and of artist and engineer. It's a tension that's exemplified in the van Toorn vs Crouwel exchange, with Crouwel seeing the designer as more of an engineer and van Toorn holding forth with a far more artistic and political take on the designer's role. There's an added frisson of tension, because the Stedelijk was exhibiting a show of van Toorn's work at the time, and the catalogue for the exhibition was, ironically, designed by Crouwel himself.

The debate paints van Toorn very much as the rebel, arguing passionately for the designer's need to retain their sense of personality and politics, despite the brief they're responding to. Years before the debate, in 1965, he stated, “It is not our job to please business”, and it's a point of view he holds true to in 72 during the debate, calling for the design world to become more daring, and to put more of themselves into their work. “In fine art, experiments have been done for centuries,” he argues. “And perhaps we should pick up more from that tradition and use more from it.”

Reading the objectivity vs subjectivity debate, it has to be confessed there's more of the 'romance' of design in van Toorn's words, and he clearly feels the artistic possibilities of the designer more intensely. Even Crouwel picks up on the antagonism of engineer vs artist, and comments, “Many designers are living with the dilemma of wanting to be a visual artist rather than a good graphic designer.”

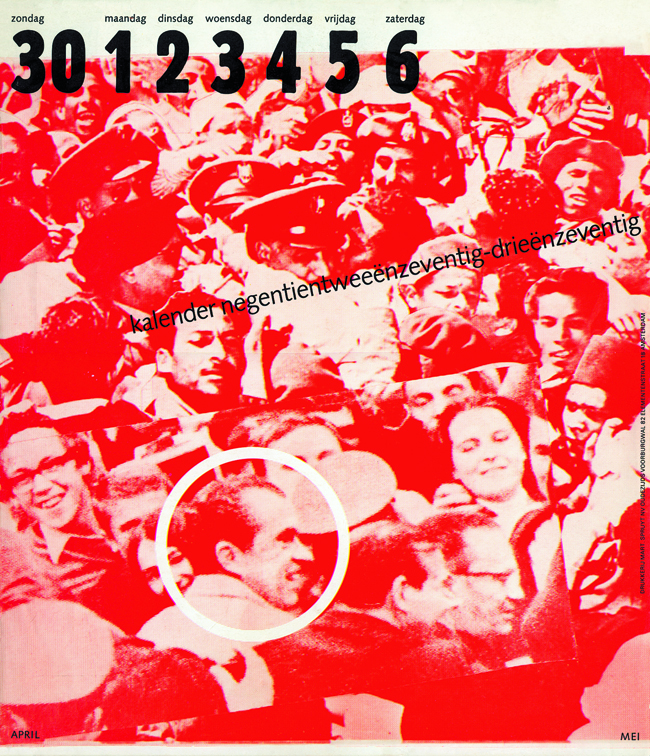

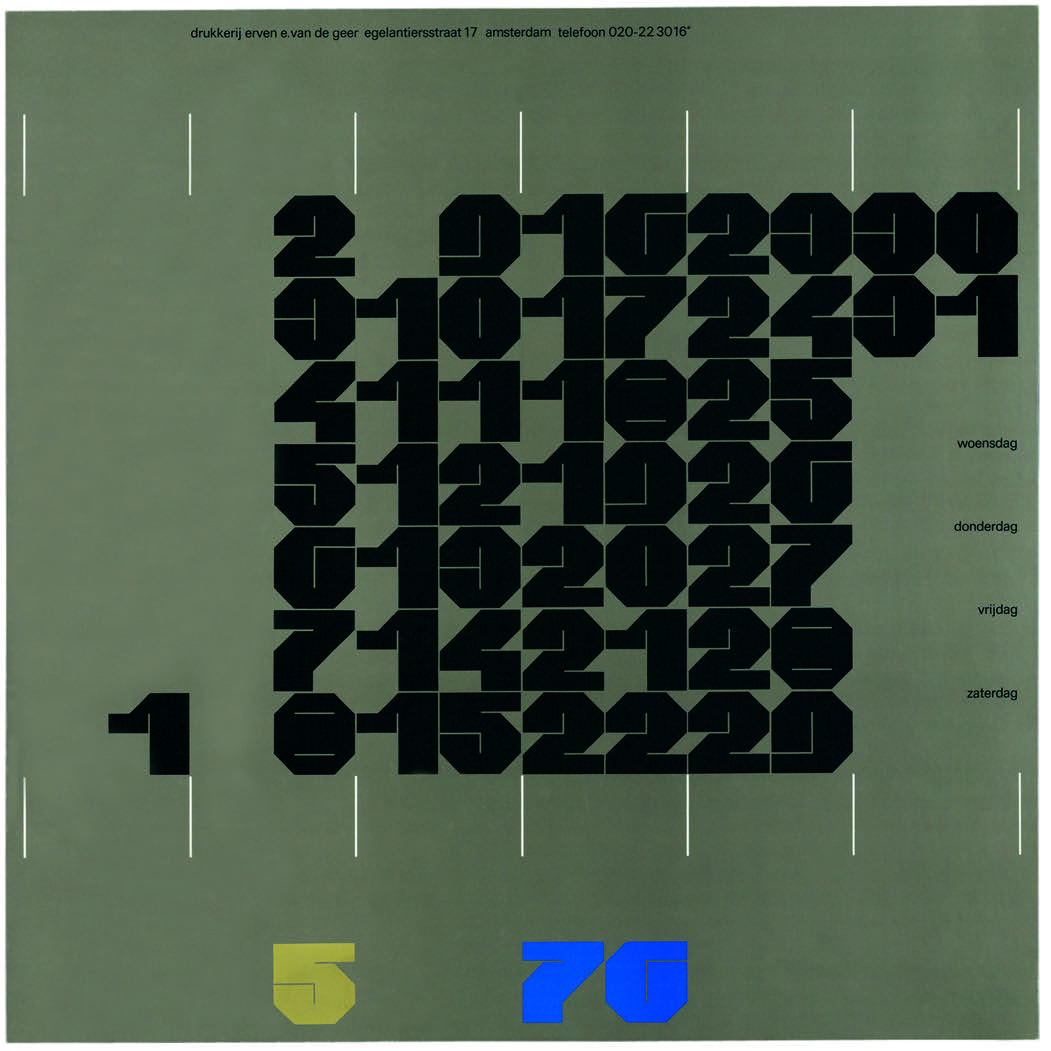

As you'd expect, bringing together two such opinionated and accomplished practitioners made for a fiery outcome. Poynor describes it as, “One of those pivotal moments in the history of a profession, when vital issues burst into flame and become a focus for discussion.” Neither designer holds back with their opinion, or shows any hesitance to criticise. Van Toorn accuses Crouwel, “To me, your approach is not relevant, and in my view you should not propagate it as the only possible solution for a number of communication problems, because it's not true.” Meanwhile Crouwel calls van Toorn's latest Sprujit calendar design “as pretentious a piece of so-called good design”. Even the audience weren't afraid to join in, with the several hundred-strong crowd interjecting with cries of “Crap!”, “Nonsense”, and “That is bullshit”, among other choice phrases.

Unsurprisingly, the debate doesn't reach a resolution, and even now van Toorn admits that while his understanding of design as a “socio-cultural engagement” has deepened, his opinion remains the same in essence. Crouwel also holds true to his original viewpoint, stating, “Although we are all children of our time, and our ideas always have a certain reflection of that time, generally my ideas have not changed that much. I have always believed that graphic design is a discipline that should translate a message in an aesthetic and straightforward way, without personal interpretation that has no connection with that message.”

However perhaps the point is less about a lack of agreement, and more about how we can relate to the issues discussed, more than forty years later. “Discussion about this subject is still relevant,” affirms Crouwel. “We live in a time that is completely different from the time of our debate. In the 70s there was a lot of opposition against design being a dangerous discipline to over-shape our world. In the 80s design was hot again. In the 90s the concept was most important. And today a certain personal expressionism is pushing design. Is that a danger for graphic design? Let the young generation have their debate!”

The Debate: The Legendary Contest of Two Giants of Graphic Design

Written by Wim Crouwel, Jan van Toorn, Foreword by Rick Poynor, Text by Frederike Huygen

Published by Monacelli Press, $24.95

monacellipress.com