Braniff International was the airline that transformed dreary plane fuselages into colourful brand statements, and buttoned-up stewardesses into sexy hostesses. In this archive piece from Grafik 181, Jason Jules tells the story of its ascent (and demise), featuring an all-star cast including Alexander Girard, Emilio Pucci and Andy Warhol.

It’s 1972, you’re female, twenty-two years old and an air stewardess. You’re cutting through the crowds at Newark Airport. Everyone’s busy with their luggage, their boarding passes, their big goodbyes; a thousand mini-dramas being played out on one giant stage. Somehow you’re immune to all this – you have your destination and you have a plane to catch too, but you swish through the throng as if you’re already gliding on a bed of air; they step aside for you, they pause and watch you go by, some of the guys, young and old, try and catch your eye – a wink, a smile. But you’re not fazed by all this attention; after all, you’re not just any air stewardess, you’re one of the select few. You’re a Braniff girl. When you’ve got it, flaunt it.

Braniff was to air travel what Rolling Stone and Playboy were to magazine publishing; a radical rethinking of everything that had happened up to that date. The story of Braniff plays out like a Mad Men-type TV series; a tale of an age gone by, where marketing men and corporate presidents were America’s modern pioneers and where being maverick was a quality to be admired, not shunned. A tale of affairs, divorces and disasters and ultimately of a collapse caused by misjudgment on a grand scale – it’s the tale of Icarus played out in modern clothes. What’s more, Braniff left a cultural legacy that we’re living with even now.

It wasn’t until the airline was bought in 1965 as a company asset for his investors by Troy Post, an insurance man, that the Braniff story really beings to hot up. Until then, its history reads like that of many other airlines. Based in Dallas and founded by brothers Paul and Tom Braniff in 1928, it initially served the Midwest and eventually expanded. By the mid-50s its reach included much of North America, South and Latin America and the Caribbean. Troy hired his brother-in-law Harding L. Lawrence to be the airline’s president. The stylish (think Don Draper) Lawrence was at that time the vice-president of Continental Airlines – one of the most forward-thinking companies in the industry – and had been regularly courted by other airlines to come work for them. His vision was to somehow turn Braniff, then the eleventh largest US aviation company, into the market leader.

As part of his summary exit from Continental (with whom he would experience fierce competition until the bitter end), Lawrence took with him marketing agency Jack Tinker Associates. Led by the ace account executive Mary Wells, they had been working on a project to market Continental’s new fleet of jets. Wells was modern and smart and cultured: for example, she had Ray and Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen furniture for her wedding (her first wedding, that is). She would drive most of Braniff’s groundbreaking campaigns. Married to different people at the time, Lawrence and Wells would eventually divorce and marry each other.

By virtue of the country’s size and its postwar prosperity, the American commercial airline industry was already way more developed than its UK or European counterparts, but it was still functioning within a cultural context established during or prior to World War II. Fares were incredibly expensive and regulated – the core thinking here was that in order to ensure the safe running of planes, the government needed to limit competition between airlines that might eventually involve lower fares and therefore, it was assumed, standards. More, this meant that the government undertook to ensure that these airlines never went bust.

Until the end of the fifties, all this meant that air travel was an option only for the rich – corporate execs, film stars, sports stars and such. It also meant that while the airlines did plenty to make their customers comfortable, they did little to differentiate themselves from each other on a mass level, doing as much as they could to please the government regulators and their wealthy passengers.

It was Bob Six, main man at Continental Airlines, who pioneered low-cost air travel. Going against common beliefs, he felt the future of air travel lay in giving the market a broader customer base – in 1962 he kicked this off by introducing economy fares to some of his routes.

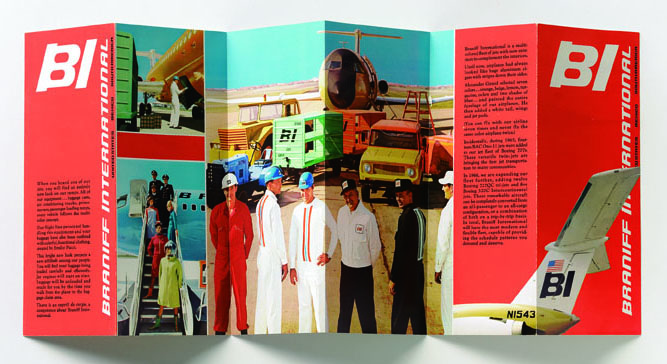

At this time, most airports resembled large cavernous military aircraft hangars. Planes were either white, with a strip running along the side of their livery, a visual gesture towards aerodynamics, or the dull grey of their steel shell. And so, with no real points of difference except routes, the new Braniff chief and marketing team were confronted with a huge challenge if they were to achieve Lawrence’s express goal of airline supremacy: how to create a sense of uniqueness from a point where there isn’t any?

They were faced with something which many designers and marketing people are faced with today; where oftentimes if there are no inherent qualities to distinguish one product or service from another, there’s no alternative but to carefully manufacture an identity. Turning Braniff Airlines into a unique brand provided a creative a template that still has currency today. The goal was to formulate a brand differentiation seemingly out of nowhere. What they did was recruit a crack creative team, all of whom brought something different to the party. Although they probably didn’t use the term at the time, what they needed was a ‘big idea’. In her biography, Mary Wells Lawrence explains: “I saw the opportunity in color the way Flo Ziegfeld must have seen an empty stage. I saw Braniff in a wash of beautiful color.”

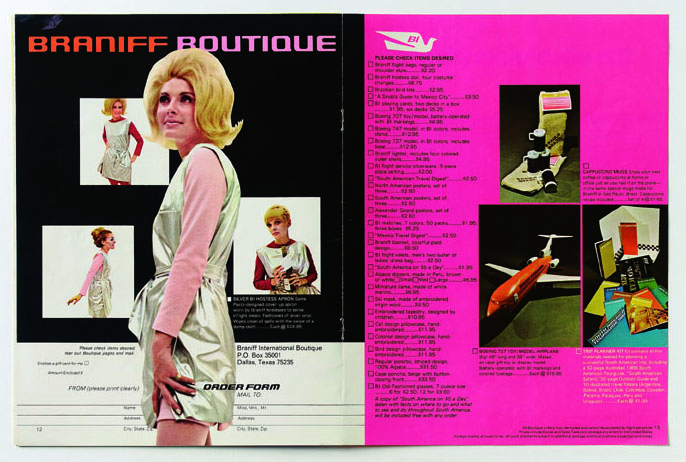

It was this overarching idea that fuelled the success of the whole Braniff phenomenon. The goal was to capture the glamour and colour of the Sixties (and the postwar optimism of the Fifties) and inject it into air travel – creating relevance and a kind of appeal beyond its immediate audience and in doing so taking ownership of the period; modern air travel WAS Braniff International.The Braniff team recruited Emilio Pucci, the Italian designer known for his prints and his passion for colour, to design the uniforms for the staff – from ground staff to pilots, with special attention to the air stewardesses, whom they summarily renamed ‘air hostesses’. These designs turned the servile, stuffy air stewardess into a strong, independent, young, available woman – not too far away from ideas found within the fashion magazines of the time, except that their sole purpose was to travel, have a good time and serve the needs of their passengers (most of whom where men). The design of their uniforms enabled the hostesses to do what was coined and advertised as “The Air Strip”, as they gradually took off pieces of outer clothing during the course of the flight. “Somehow we got the idea that Braniff routes always took people from cold places to warm places,” explains Wells Lawrence. Further, Braniff made space age-style helmets for its air hostesses, to protect their hairstyles while cutting through busy airports, and bikinis in which Pucci ensured they were photographed for press purposes at any given opportunity.

Then, in an inspired move, the Braniff team recruited Alexander Girard. Raised in Florence, Girard studied architecture in Rome and ended up as a textile designer in New York working with Herman Miller and the Eameses. Like Pucci, whom he’d coincidentally known growing up in Florence, his thing was colour – Mexico and folk art being big themes in his work. Braniff was the kind of branding gig designers usually only ever dream of: to design the interiors, the check-in counters, the club lounges, the serving trays, the seats and, most importantly, the plane’s livery. Later, in 1973, Alexander Calder took over the gig that Girard had initiated.

The kernel of the whole idea, that thing at the very centre of it, was to make the planes themselves a visual statement, an object that differentiated the Braniff ‘way’ from all others’. Wells Lawrence had already come up with the idea by the time she commissioned Girard to paint each of the airline’s fleet of Boeing 707s different colours – seven in total – including green, red and turquoise. It was this, and the advertising tagline “The End of the Plain Plane”, which created the before-and-after effect Braniff chief Harding Lawrence had hoped for. So radical was the idea of adding colour to the body of the planes that it immediately acquired press all over the world. The initial response from other airlines was shock. Some even argued that painting the livery added a dangerous amount of extra weight to a plane, but, as with most of the Braniff innovations of the time, the idea was soon copied throughout the industry. In 1968 Continental Airlines, taking a leaf out of the Braniff look-book, hired graphics guru Saul Bass to redesign its logo.

But even before the deregulation of US air travel in 1978, the Braniff glow was beginning to fade; it wasn’t that the idea had run its course, or that those behind it had lost confidence in this grand project, it was that they had too much confidence in it and believed its potential was limitless. The tale of Braniff and Harding Lawrence is a case study not only in the power of marketing and image but also its weaknesses. If “The End of the Plain Plane” was a statement of intent, then “The Air Strip”, followed by copy lines like “The Most Exclusive Address in the Sky”, were indications of a growing arrogance. In fact, it became less and less about the experience of flying and more about the power of advertising and the sweet smell of success.

Ads like “When You Got It, Flaunt It”, are a neat example of the fine line which the brand walked between branding and bragging. Imagine: Sonny Liston sitting next to Andy Warhol on a plane. Andy: Of course, remember there’s an inherent beauty in soup cans that Michelangelo could not have imagined existed...Voiceover: Talkative Andy Warhol and gabby Sonny Liston always fly Braniff. They like our girls, they like our food, they like our style and they like to be on time. Thanks for flying Branif,f fellas. Andy: When you got it – flaunt it. Voiceover: Braniff International. When You Got It – Flaunt It.

While others saw deregulation as something to adapt to with caution, Lawrence saw it as a starter gun for rapid expansion, a process which included joining forces with Air France and British Airways on the doomed Concorde project, new internal and international flights and a brand-new state-of-the-art headquarters in Dallas. Spiralling debt was the outcome, and the involvement of Lawrence in a tax-fraud scandal only added to the Mad Men-type drama and Braniff’s eventual bankruptcy. And so it was that the Lawrence era ended in 1982.

Perhaps Braniff’s real legacy is outside the aviation industry: its complete-branding innovations and belief in the blend of art and commerce are now standard practice in the creative industries. But it’s a different world in which we travel today: Bob Six’s notion that commercial aviation would be all about cheaper flights has come true. It’s more about the destination and less about the journey these days. The notion of glamour has all but disappeared – in fact, the current thinking is if you got it, whatever you do, don’t flaunt it, or you’ll be charged extra to get it on the plane.