The Barbican’s new exhibition Magnificent Obsessions pairs the personal collections of fourteen post-war artists with their own work, exploring echoes in each and raising pertinent questions about taste and beauty.

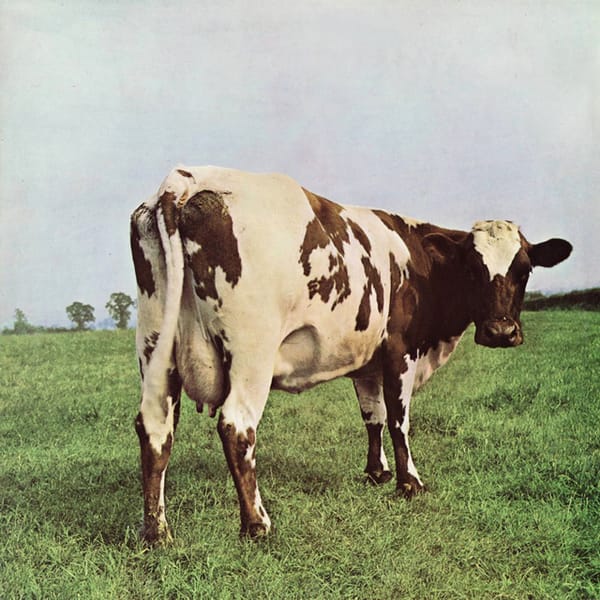

“The word ‘museum’ comes from ‘mausoleum’ in many ways,” says Lydia Yee, the curator behind new Barbican exhibition Magnificent Obsessions. “Once you put a collection into a museum, it can deaden it. That’s exactly what we didn't want to do here.” The show, which runs until 25 May 2015 in the Barbican Centre’s main gallery, brings together the personal collections of fourteen post-war and contemporary artists, from Andy Warhol’s ceramic cookie jars and Peter Blake’s wooden elephants to ceramicist Edmund de Waal’s netsuke (small carved Japanese animals and figures) and Martin Parr’s wealth of British postcards and printed ephemera. Its aim is to explore not only how these treasured objects inform and inspire the artistic practice of their owner, but how collections made by artists differ from those undertaken by a museum or cultural institute.

For most, collections begin in childhood, a period, as Yee points out, that also coincides with the most creative period in our lives. “We're able to do crazy, inventive things and make our worlds out of the objects that are around us,” she explains. “These artists are able to continue with this activity into adulthood.” Perhaps unsurprisingly, the link between collection and the resulting practice often runs deep. For example, Damien Hirst’s collection of taxidermy (including a pangolin, seven-legged lamb and several pieces by Victorian taxidermist Walter Potter, who also pops up in Peter Blake’s collection), are very closely tied to his formaldehyde-encased beasts or the suspended butterflies of 2013’s Entomology. But the exhibition also reveals (indeed the exhibition text for Magnificent Obsessions frequently offers truly insightful gems) that as teenager Hirst traded artworks with peers, buying more valuable pieces as his success grew. Within this action, the idea of art as an act of collecting rather than making was formed, plus an interest in the art market and how it values works – something reflected in For The Love of God, his £50m diamond-encrusted skull that on creation was thought to be the most valuable piece of contemporary art in existence.

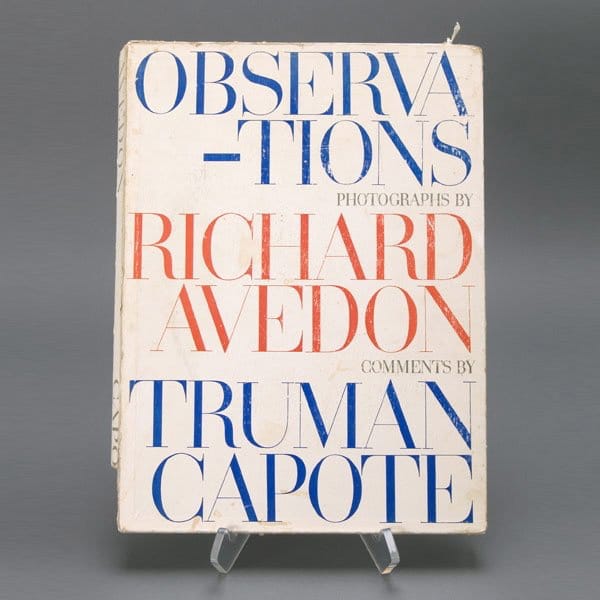

For Yee, her initial interest in the concept of the artist as collector (and the background to this exhibition) was sewn during numerous visits to artists studios during curation projects and observing what they had on their walls, from postcards and research material to artefacts they’d collected and displayed. Intrigued at their purpose in the studio and how the collections ‘live’ in that space, the exhibition that really focused her ideas and led to her to think about transferring the pieces into a gallery context was Hiroshi Sugimoto’s 2005 exhibition History of History at the Japan society in New York. There Sugimoto (whose anatomical drawings are the first pieces you come to in the Barbican space) presented Japanese antiquities, religious objects, and artworks, as well as fossils, alongside his own photographs. “One of the things that really struck me about his collection was that he took certain liberties with the objects in a way that I was quite surprised by at the time,” explains Yee. “For example he took an old Japanese scroll and mounted one of his seascape photographs directly on to the surface, irreparably altering the work for time. It was a bit of a shock to see that he had altered or destroyed this scroll but it became something else in his hands as a work of art.”

Although Hirst’s taxidermy and Sugimotos mezzotints by Jaques Guatier D’agony (many of which depict women in traditional portraiture poses but with the muscles and skeletons exposed) flirt with the macabre, many of the collections attempt (whether consciously or not) to unpick taste and what constitutes beauty. Jim Shaw’s hoard of paintings bought from thrift stores range from just bad to disturbing (a portrait of a blonde woman bearing her teeth is, I assume, unintentionally terrifying), but shed light on a world of artists operating without the expectation of being exhibited. Martin Parr’s postcard collection, which he started in the 70s while working at a Butlins Holiday camp (another textual insight that makes so much sense in retrospect) touches on the performative aspect of holidaying and documenting that experience, something he plays with in his own photographic explorations of Britain’s tourist industry.

Perhaps what’s most impressive about the show is its understated and domestic-inspired design, realised with the help of Dyvik Kahlen Architects, which added carpeting, second-hand vitrines and shelving and colours that evoke the artists’ walls. Yee explains: “The Barbican space is challenging. If you look at the architecture on its own it's very brutalist and heavy with very strong details. I didn't want a clinical display. If we had just put everything into white cases and on white walls in a bare space, then it would have looked like any other museum exhibition.”

Catering for different levels of engagement is something that Barbican shows always excel at and with Dyvik Kahlen Architects’ design you are made to feel comfortable either perusing objects that take your fancy or meticulously delving into the content (with the help of the exhibition’s excellent app). The result is an exhibition that feels inviting, much like walking into an artist’s studio or home, and is incredibly accessible, but – if you choose to seek them – asks bigger questions about beauty, the links between consumerism and identity, and the gallery space’s ‘failure’ to replicate life. Magnificent Obsessions: The Artist as Collector

Barbican Gallery, London

Until 25 May 2015

barbican.org.uk