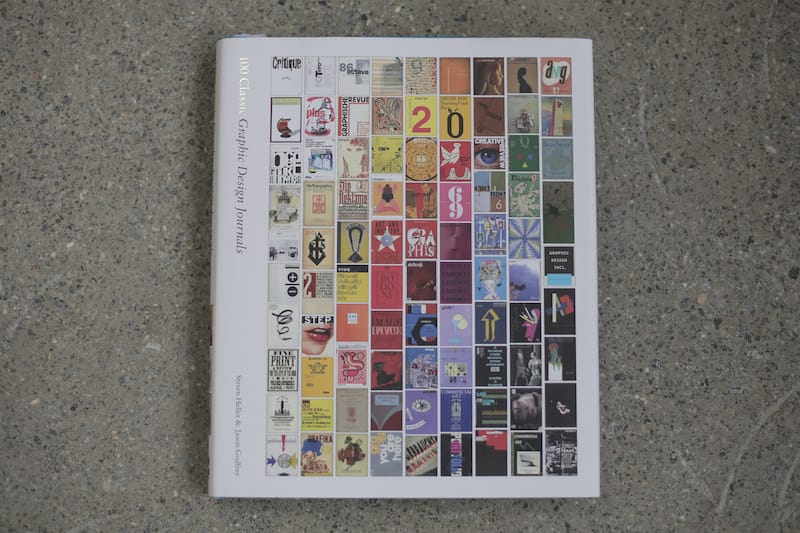

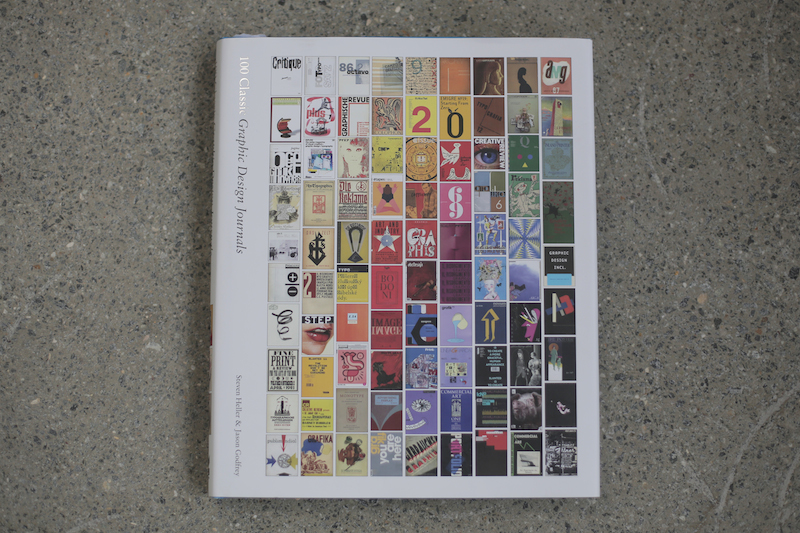

A solid starting point for further exploration, Steven Heller and Jason Godfrey’s 100 Classic Graphic Design Journals extensively examines groundbreaking magazines that have helped shape the discipline.

The past fifteen years have been a period of extreme change in the world of print magazines. With the birth of the internet and its culture of free content, and the ever-spiralling cost of printing and paper, the landscape of graphic design journals has become a rapidly fluctuating scene, littered with casualties, inventive independents that defy traditional publishing models, and constant evolution. You only have to look at Grafik’s own trajectory for an example of this. But, as can be seen from Laurence King’s new book 100 Classic Graphic Design Journals, such flux is not just contained to present day. The book, which chronicles design publications from their beginnings in the nineteenth century as guides for professional standards for printing and typography to current titles, is packed with narratives of change and innovation, shaped by two world wars, internal and external political pressures and rapidly changing technology.

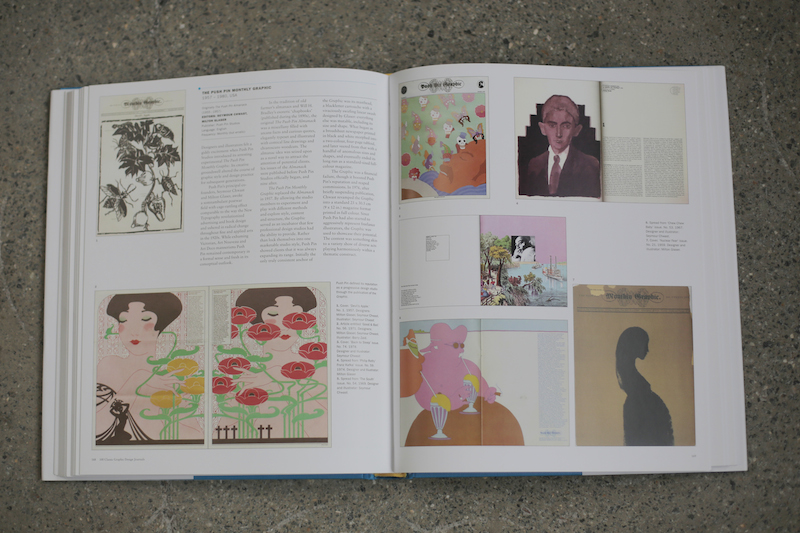

“Early graphic design journals are the missing link in the development of the cannon and its style,” claim authors Steven Heller and Jason Godfrey in the book’s introduction. “They are the historical records of both lasting and ephemeral method and madness.” In many cases this is very hard to argue with. Because of the commercial nature of advertising and graphic design, journals and magazines are often the only places you can find early projects documented, as creative work often fades into obscurity after a campaign has run its course. But Heller and Godfrey also argue that the design journal had a much more active role in the profession’s early days and was instrumental in defining what graphic design was before the term even existed. Key titles like the US’s The Inland Printer, which launched in the 1890s, introduced the print industry to new art movements like Art Nouveau (largely through showcasing the work of America’s first graphic designer Will H. Bradley, whose own magazine Bradley, His Book also features in the top 100 list), dramatically upping the standard of the print room’s output and shifting the view of the discipline as a necessary by-product to an autonomous practice in itself.

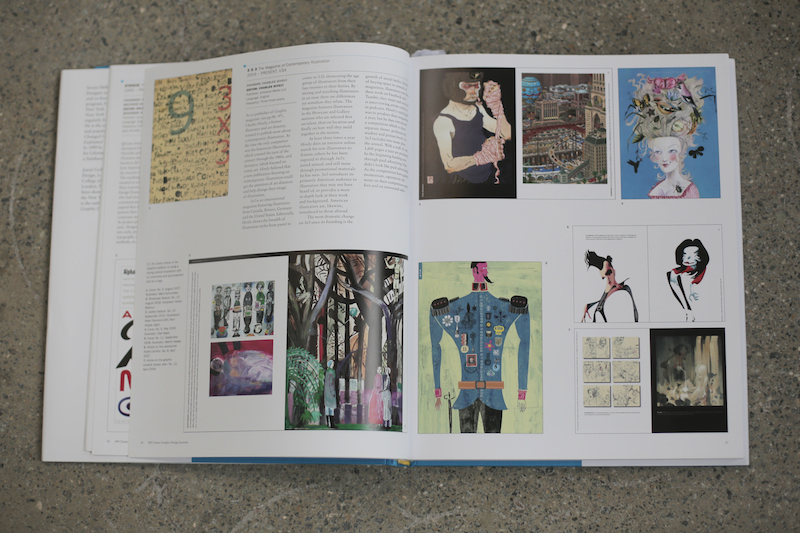

Heller and Godfrey’s selection mixes these historically important titles with contemporary publications, prioritising magazines that have been particularly groundbreaking, influential or speak particularly eloquently of their time. What links each of the 100 entries, aside from the quality of the work showcased, is the way the authors have eked out a sense of narrative behind each of journals and their legacies. As you would expect from Heller, each is meticulously researched and loaded with both fact and context, and many feature insight from current editors about their ethos and evolution. There’s a good spread beyond the obvious, taking in generalist graphic design titles (Creative Review, Eye and us, for example) as well as those with a more niche output (the US’ illustration bible 3 x 3 or Czech Republic’s Typo). There are also some unexpected gems. Neshan, an Iranian graphic design magazine set up by a group of like-minded practitioners in 2003, is one such example. Documenting a design scene largely unknown outside of Tehran, the magazine faces challenges of religious, cultural and social limitations but, as Heller points out, these limitations have spawned a creative design language quite of its own.

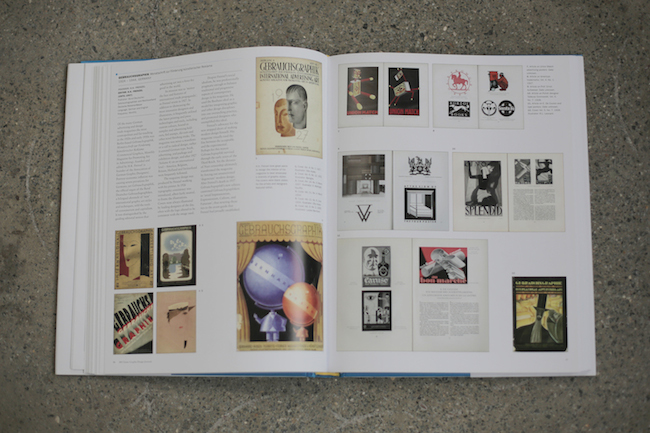

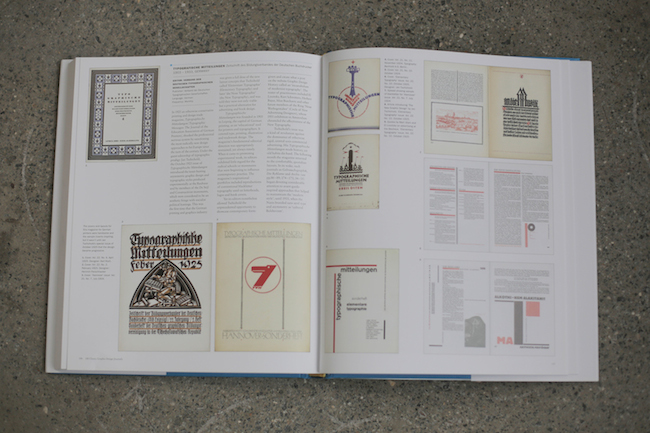

Where the editorial is at its best is when Heller and Godfrey have space to draw parallels between publications and give a wider view of the landscape that they sit within. Its foreword for example, features a lengthy segment focusing on the lineage of a number of German publications, due, one might suspect, to the huge creative innovation (and censorship) the country’s design scene experienced between 1900 and 1945. There’s a recurring narrative of the avant-garde butting against traditionalist opposition. Typographische Mitteilungen, the monthly publication of the German Printer’s Association in Leipzeig, caused shockwaves throughout the industry when, under the guest editorship of typographic radical Jan Tschichold, it made history by showcasing avant-garde design from the Bauhaus, De Stijl and Constructivism. Complaints were rife and sadly the title returned to a more straight-laced approach the very next issue. Similarly radical, the idealist founder of bi-lingual English and German publication Gebrauchsgraphik, H. K. Frenzel, felt that advertising art was a force for good in the world and could, through showcasing international art movements and ideas (as well as native talents), bring understanding between nations and achieve peace. Sadly, as the Nazis came to power, the magazine changed beyond recognition as party sanctions stipulated the removal of all ‘degenerate’ design, and after Frenzel’s death (purportedly a suicide), new editors were asked to tow the line, avoiding the expressive styles that had made the title so interesting.

With the success of the foreword in mind (and its bent on evolving narratives) it seems a shame that some of the connections a reader could make between related titles are broken up by the entries’ alphabetical ordering. That said, grouping them instead chronologically or by country would introduce other profound problems (where do you place a title that spans 50 years or something truly international in scope?). Like ordering your record collection, there is no perfect solution and it's an issue that every compendium-style book falls victim to. Perhaps a book centred around themed chapters might make a better read, but that is not what this book aims to do, and nor would that approach be able to cover quite so much ground. 100 Classic Graphic Design Journals

By Steven Heller and Jason Godfrey

Published by Laurence King, £30