You've never seen anything quite like this — an under-appreciated giant of the European comic book canon is revived.

How to describe The Adventures of Jodelle? A political satire, certainly; a watershed moment in the history of graphic story telling, without question; a salacious exploration of mid-century innuendo, most definitely. To do it justice, however, you have to be quick and to the point: guns; sex; monsters; death; motorcycles. We should all be grateful that a young Guy Peelaert dropped advertising to indulge his interest in comics. The result was an artefact that has impacted far beyond the boundaries of genre, a comic book whose influence in the history of fine art and popular culture is not now widely enough recognised.

Fantagraphics's re-editioning of the work may go some way to addressing that. The book consists of a remastered and digitally recoloured version of the comic, accompanied by a new, even more idiomatic translation (“baby”). Following this is an essay — The Jodelle Style — by Pierre Sterckx, alongside a considerable biography of the artist’s career illustrated with both finished and in-process materials from the artist’s estate (It’s fascinating to discover that on a 1964 excursion to New York the artist spent time with Warhol and had a mysterious meeting with Push Pin Studios). A concerted attempt to fix both Peelaert and Jodelle back in the firmament, the publication has been produced with real care, both in regards to the treatment of the art work and its art historical contextulising.

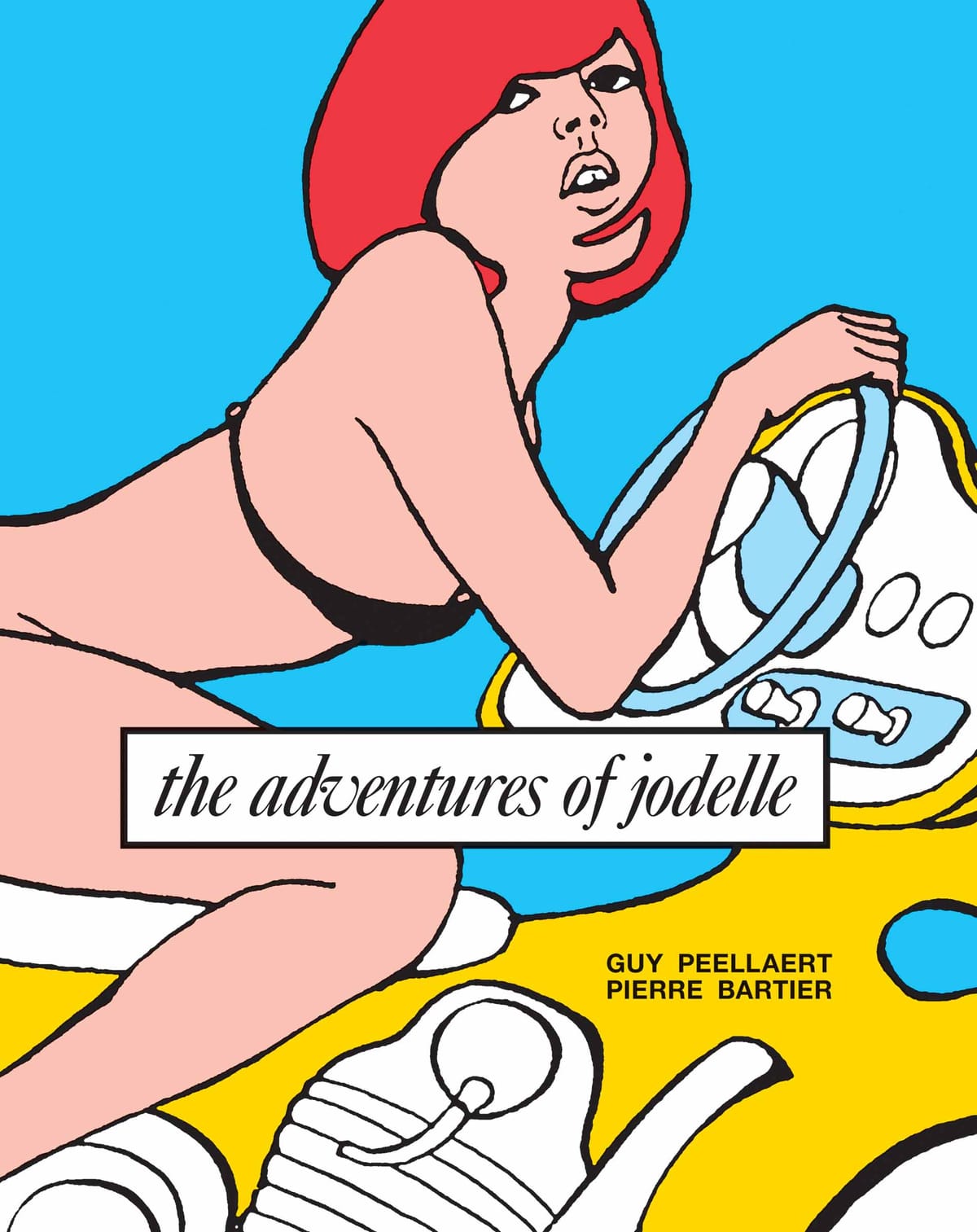

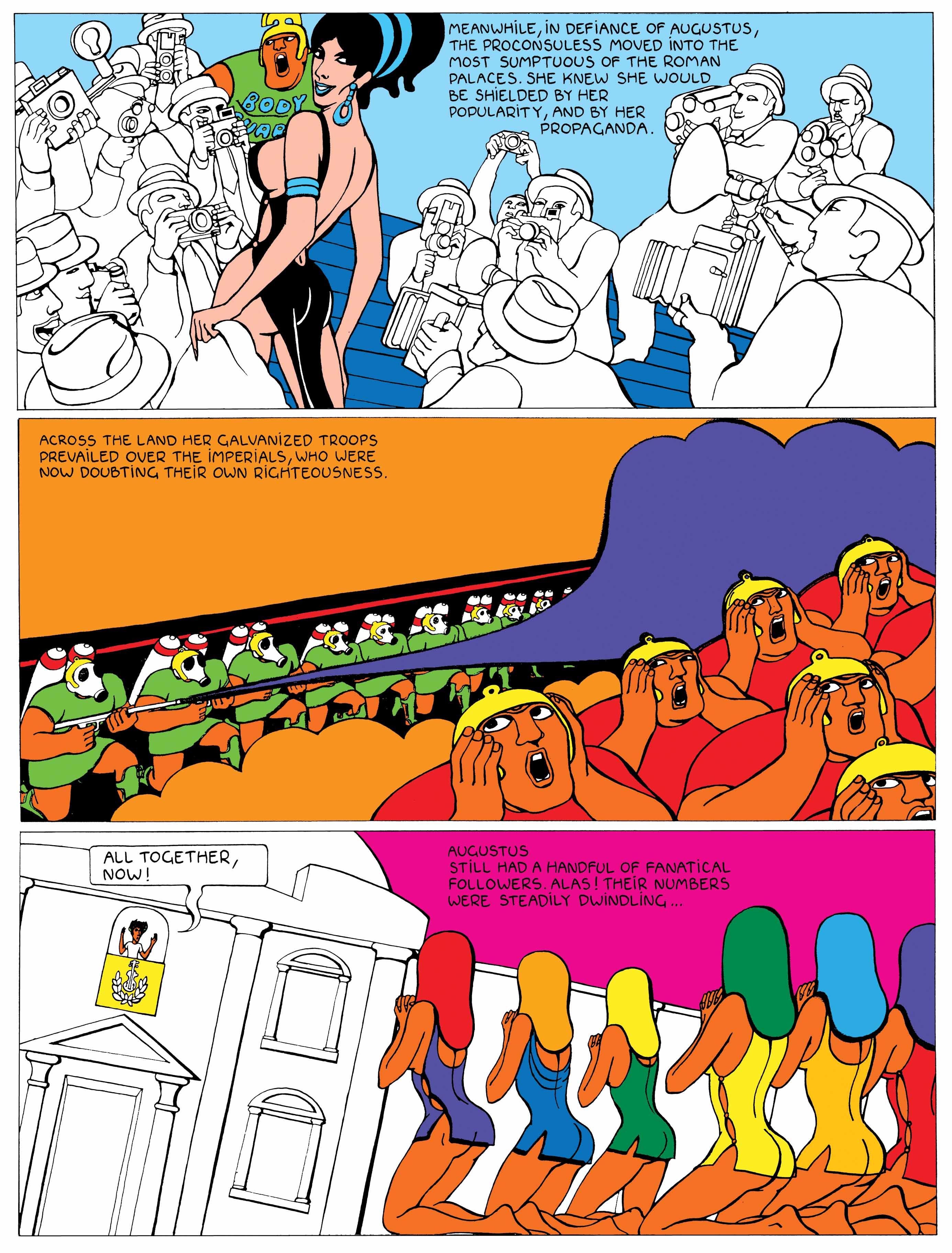

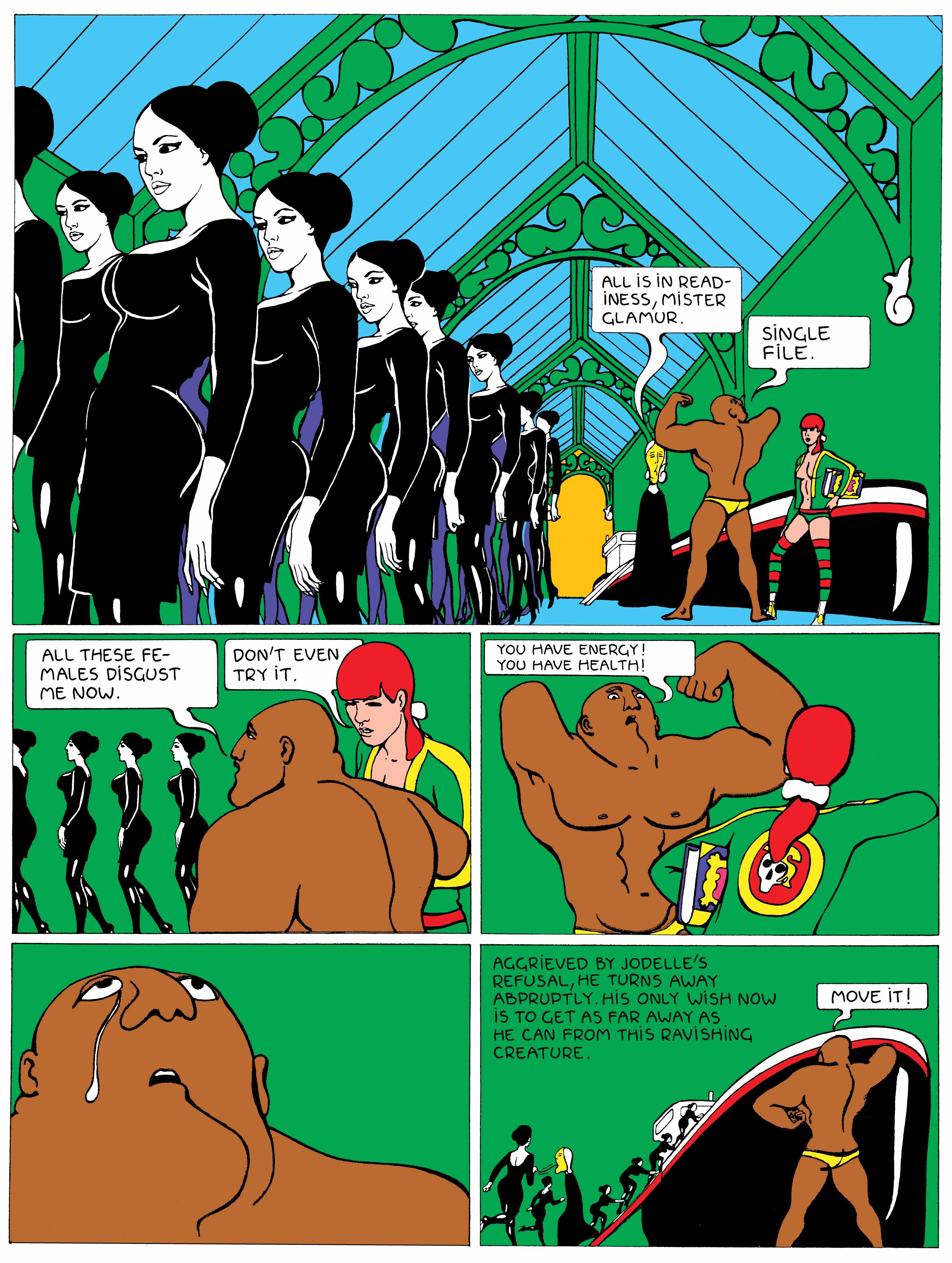

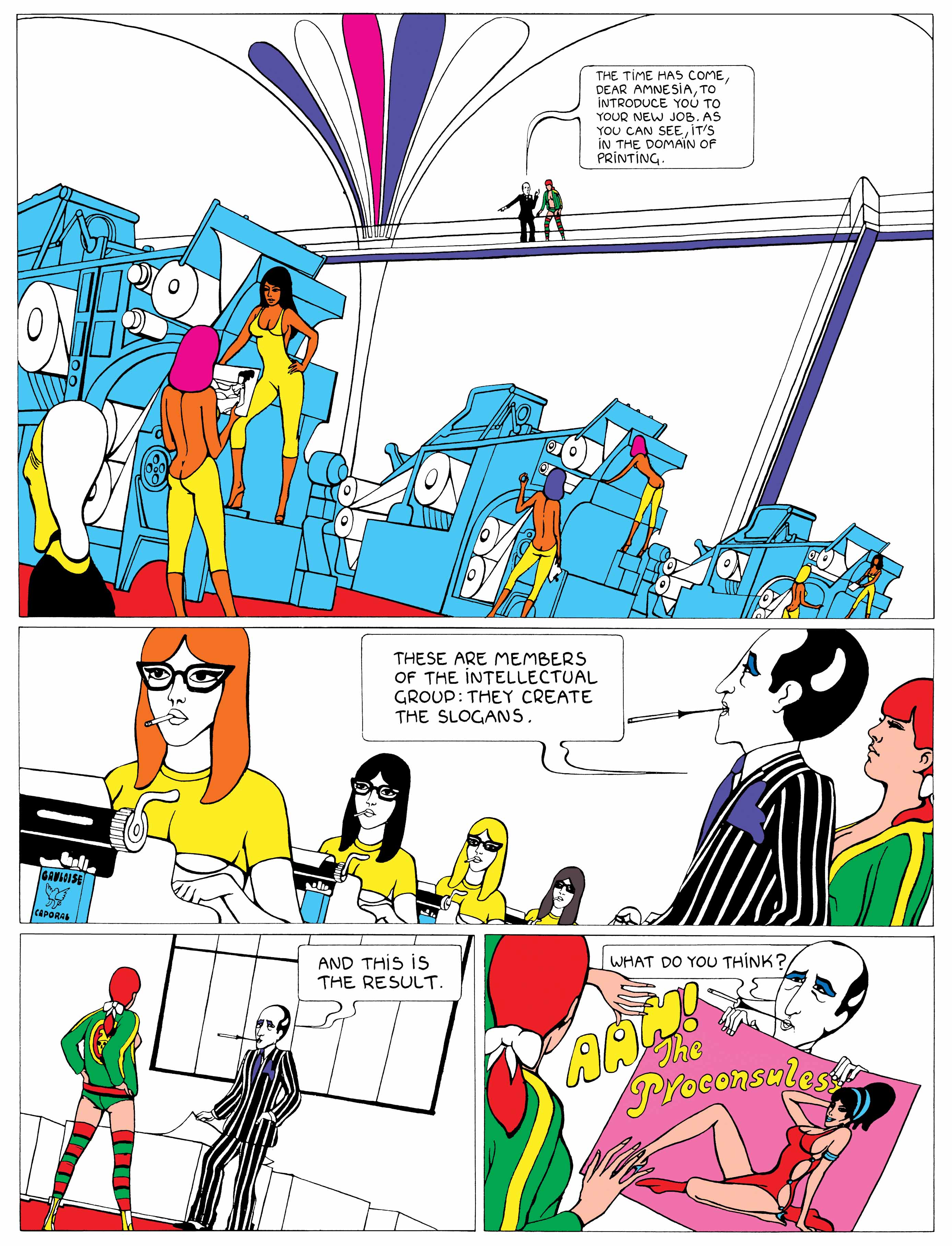

Set in a destabilising locale, somewhere between France, America and ancient Rome, the titular Jodelle (modeled on teen idol Sylvie Vartan) is a fem-spy extraordinaire who holds few allegiances other than to the emperor Augustus, a proto-Beatles front man complete with Stratocaster. Indeed it is the defense of his name and position against the machinations of the terrible, though equally young, attractive and prurient Proconsuless that is the basis for Jodelle’s adventure. There is a consciously underwritten backdrop of political archetyping, with the tyrannical Proconsuless happy to disrobe any of the empire’s democratic structures in order to fend off a “socio-economic downturn”, a fable of 60s francopolitics.

Jodelle’s visual style was equally striking, with sharply defined areas of saturated colour corralled by thick black lines – no other comic book had delivered a graphic language as emphatic as Peellaert’s. The palette is a mixture of lurid greens, plastic reds and sunburst yellows, the combination pitched somewhere between psychedelia and a supermarket shopping aisle. This is pushed to the limit in this new edition, taking advantage of technical improvements in colour reproduction when compared to the softness of, say, the 1968 Grove Press edition. The use of pure colour without reproducing any of the halftone dot patternation and the tidying up of any bleeding does however neutralise some of the original’s textured irascibility.

While clearly influenced by them, Jodelle supersedes any attachment to the British or American Pop scenes with which it was contemporary. Pierre Sterckx, in his accompanying essay, suggests that Peelaert “might even be called Rococo, a mannerist of the Baroque beyond the graphic level.” This is as much a reference to the his use of source material as to his graphical deployment. Rather than shifting the low to the high with the familiar transposition of content elevated by form, Peellaert created a visual anticyclone. Here cultural stratification is flattened and things are marked out only according to the strength of the artist’s passions. Peellaert had no recognition of what he called ‘“nobel” objects’, and for him history appeared more as a singularity than a continuum; thus the world of Jodelle is one in which Frank Lloyd Wright, Caligula and French yé-yé girls are all naturalised citizens.

And while Peellaert was quite happy to accept associations with the likes of Warhol, Lichtenstein, Hamilton or Paolozi, the main aesthetic impetus behind Jodelle was in fact the Gottlieb pinball machines in front of which he’d spent so many frantic hours. Once this fact is known, it is easy to see its incongruous truth – in the way each pane contains enough dramatic tension to be a self-sustaining entity, or in the ethereal glow the lights each shadowless scene, or in the hard ricocheting quality of the action as characters run hard into their bounding containers. This is a book to sweat over, to shout at and to get drunk with. If it could have been coin-operated they could have installed it in troquets all over France.

The Adventures of Jodelle, by Guy Peellaert and Pierre Bartier

Published by Fantagraphics, £25