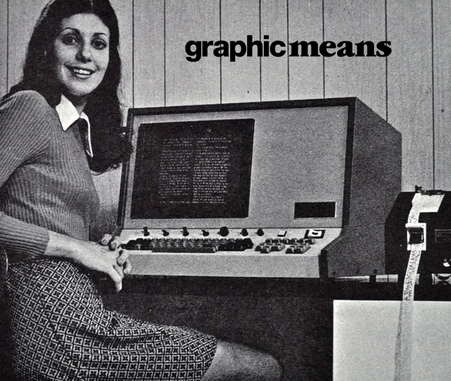

Briar Levit's new film project Graphic Means aims to document the lost art of pre-Macintosh methods of graphic design production. Read on to find out how you can get involved.

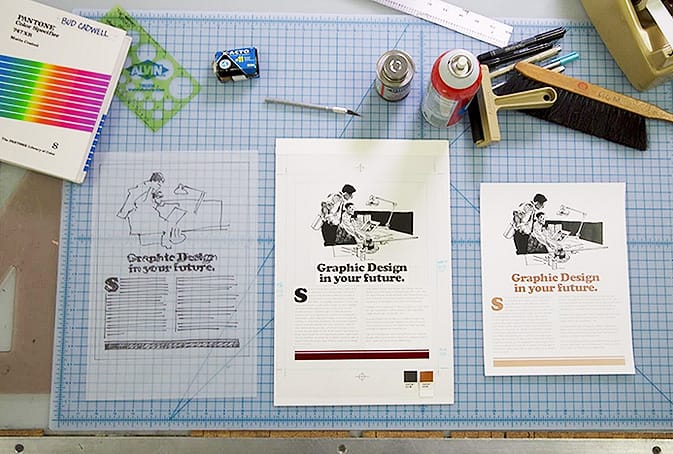

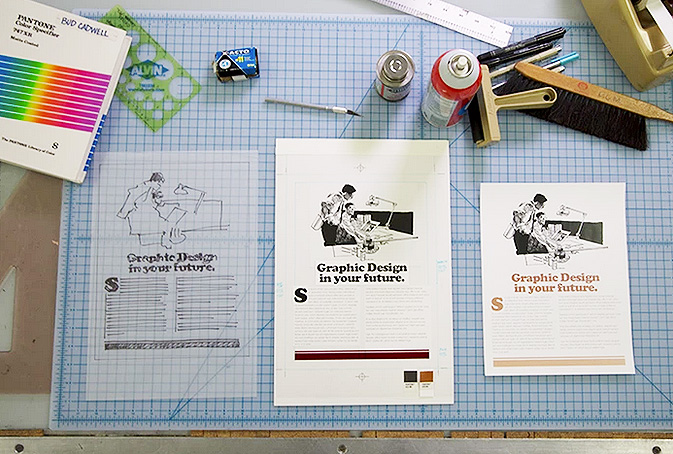

Tell us bit about how the project first come about...Graphic Means started as I found myself amassing a collection of obsolete graphic design production manuals from the Goodwill. I would pour over these books and just be amazed at the amount of time, skill, and tools that were used to make simple things like a brochure ready for print.

I started studying design in 1996, and my school had already converted to using computers, so while there were some holdovers to that era in my education (for instance I had a class in which I learned marker illustration techniques, and we were required to mount work with a cover sheet neatly taped over the board), these were not things I used once I graduated. Looking at these manuals was a window to an era of design that fascinated me both from the technical stand point, but also from a social stand point. I began to wonder more about the relationships between all of the professionals needed to get a piece of work ready to print from the designer to the typesetter, the paste-up artist, perhaps photo retoucher, etc. Side note: Wouldn’t it be cool if there was a spin-off to Mad Men that focused on the designers, letterers, typographers and other production folks?

It’s wonderful that younger designers are often aware of the greats like Saul Bass, or Joseph Müller Brockmann – but if you can understand the level of skill they had, and the amount of work it took to make their master works, not to mention the other people who worked with them to realise these works, then I think you have a whole new level of appreciation.

What have you learned from your initial research and interviews?It’s probably no surprise that almost no one wants to return to a workflow that doesn’t involve computers. That said, there is definitely some nostalgia about working with your hands, and working more as a team in the ways they used to.

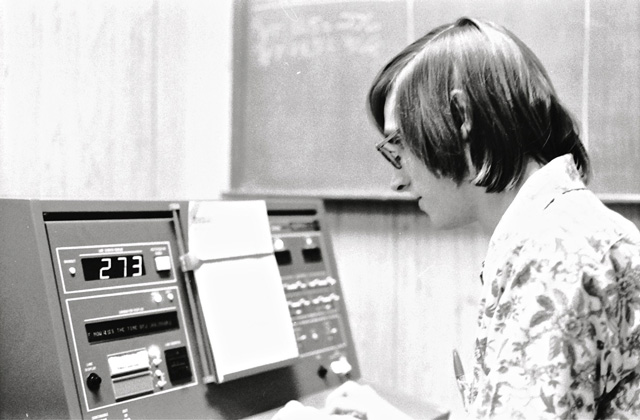

One of the recurring stories I’m hearing is about the initial introduction of say, a single Mac into various design studios, and how the designers reacted. For many, they had to be forced eventually by their bosses to learn. Some thought it was a passing fad, some just didn’t want to have to learn this new skill. Of course many typesetters, and some designers were unable to make the transition, and their careers in the field ended then. Do today’s graduates have any concept of what pre-computer ‘production’ involved?As far as I can tell, graduates of today don’t have much, if any idea about how production worked before the Mac. They may know the term paste-up, and have a vague idea of what it is, but not much more than that. It’s not that they aren’t interested when I mention some of the methods, but I think it’s pretty abstract to them – they can’t even picture it. I’m hoping Graphic Means clarifies this for people, in the same way that Doug Wilson’s film, Linotype did for me, and linecasting.

Why is it important for young designers to learn about these obsolete ways of working?As an educator, I was trying to figure out a way to bring this history into the classroom. It’s hard to fit it in, to be honest, though. We focus primarily on design thinking and technique with the brief time we have. When history is discussed, it’s much more from the theory standpoint – movements, typographic progression, specific designer profiles etc. Of course, all students learn about Gutenberg and his letterpress because it was the beginning of mass produced printed materials for the western world (props to China for actually being the first to use this technique), but students generally don’t learn about what came after that. There was linecasting (Linotype and Monotype), and photosetting (Linotron, Photon), and then digital systems that predate computers (Compugraphic composition systems). There’s a LOT that happened in between the letterpress and the Macintosh.

I don’t actually think you have to know this history to be a good designer, but I do believe it really enriches your understanding of the field – the people who came before you, the roots of terminology, etc. I just feel proud to be a part of the progression, I want others to have the feeling too.

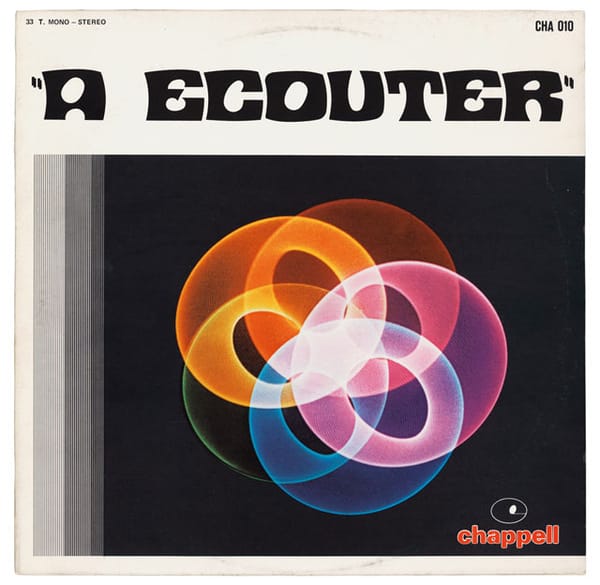

Do you think we’ll ever see a return to any of the manual means of production such as rubdown lettering or airbrushing, in the same way that letterpress and signwriting have made a comeback?I don’t think so. I mean, rubdown lettering does get used by a small group of super-fans, but that work tends to be more in a fine art vein. Now airbrushing on the other hand? I could see that. There are textures that are unique to it, that Photoshop can’t replicate. I’d love to see it, personally. I grew up adoring the fantasy art and lettering of Roger Dean on Yes album covers, and there’s just no way those works would look the same if he’d done them in Photoshop.

How can people get involved?It would be great if people can back and share the project – we need all the help we can get in making our Kickstarter goal. There are some pretty sweet rewards for donors. Also, they might want to follow us on Twitter, Instagram or Facebook – I love posting archival photos there. It’s a nice way to follow along as I continue my research.

Find out more about Graphic Means and how you can support it here, but hurry as the Kickstarter deadline is fast approaching.