The most comprehensive exhibition of digital creativity ever staged in the UK, the Barbican’s landmark show Digital Revolution strikes the right balance between awe-inspiring projects and interactive fun.

Entering the Barbican’s new exhibition Digital Revolution is a complete audio-visual assault. Restlessly competing for attention from the gloom of the Curve Gallery’s darkened recesses, an anarchic wall of TV screens flit between film clips, advertisements and the exhibition’s visual identity. The show’s pumping soundtrack feels just as erratic, darting between edgy pop tracks like Aphex Twin’s Windowlicker and Grandmaster Flash’s The Message, while bleeps, zaps and explosions overlay the soundscape, exuding from the large grid of computers and gaming devices below.

It’s easy to feel as though you’ve accidentally wondered into an unusually hip arcade rather than a gallery space. There’s a party atmosphere, and although this landmark exhibition has important work to do – namely showcasing the innovators that have pushed unthinkable boundaries in the intersection between art and digital technology from the 1970s to the present day – it’s clear that that the show’s curator, digital art expert Conrad Bodman, wants us to have some fun. This seems indicative of the Barbican’s approach to exhibition-making at the moment. You only have to look three floors above to The Fashion World of Jean Paul Gaultier (the show that it can be assumed prevented Digital Revolution from occupying a more natural home in the main gallery space) to see an excellent example of how digital technology (including an app and projections) is being applied to a non-digital subject matter.

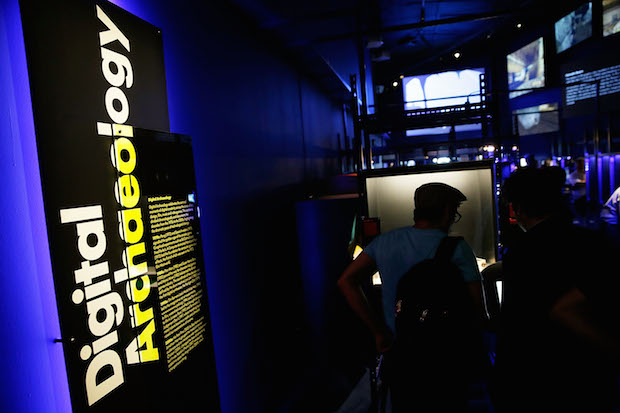

Ambitiously crammed into the The Curve gallery’s narrow environs, the show’s first section, Digital Archeology, is dedicated to mapping out the key pieces of software and hardware that signal creative breakthroughs in the world of digital art or gaming. Many are instantly recognisable: there’s Atari’s first masterpiece Pong, the crude version of table tennis that hit such mainstream popularity that it caused a rush of intellectual and financial investment into the then fledgling games industry, reshaping that world forever. There’s also 1985’s Super Mario Bros, designed by Shigeru Miyamoto for Nintendo, which spawned numerous sequels and began the phase of side-scrolling games that defined that decade.

But it’s not just console games on display, although there are there enough to eat though afternoon like a hungry Pacman. There’s a Linn LM-1 drum machine (as used on The Human League’s Don’t You Want Me), a 70s CGI ‘jukebox’ showing clips of pioneering CGI usage, and a Quantel Paintbox, the digital painting device that revolutionised TV graphics. There are some early examples a digital art too. One wall hosts Susan Kare and Bill Atkinson’s reworking of Japanese artist Hashiguchi’s Lady Combing Hair, one of the first images ever shown on a Macintosh, when launched by Steve Jobs in 1984. Builder Eater, a 1977 piece by artist Paul Brown (one of the generative artists known as the Algorists), features two simultaneous random walk algorithms that create paths across the screen one turning pixels on and the other off in a futile cat and mouse chase. Perhaps most affecting is Olia Lialina’s My Boyfriend Came Back From the War, a multi-frame artwork that allows you to navigate through the narrative of a sad and unsettling piece of web-fiction. Tight on space and arcade-like in structure, its difficult not to feel that this first section is a tad crowded, especially as the huge focus on interactivity (the ASCII camera, which prints you out portrait in ASCII code, is a particular highlight) means most of the exhibits can only be by one person at a time.

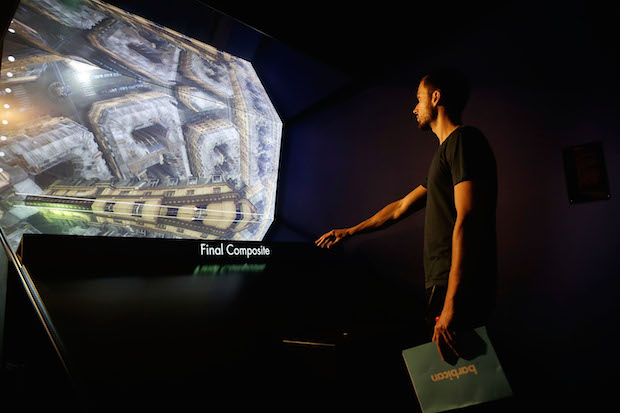

This changes in sections We Create, Creative Spaces and Sound and Vision, which showcase crowd-creating projects like Chris Mil and Aaron Koblin’s tribute website the Johnny Cash Project, the influence of rapidly changing VFX technology on film /and digital innovation in the music industry. There’s a good mixture of big industry players such as Tim Webber, the lead VFX specialist on Gravity, as well intriguing new practitioners like James Bridle, whose Dronestagram project is an Instagram feed that uses publicly available resources like The Bureau of Investigative Journalism and Google Earth Satellite View to record the locations of American drone strikes in Yemen, Pakistan and Somalia.

But it’s perhaps the latter stages of the show where the exhibition really comes into its own. State of Play exhibits a number of interactive artworks creating using camera-based systems like Kinnect. Based on the poem A Nocturnal on St Lucy’s Day, Being the Shortest Day by John Donne, Rafael Lozanon-Hemmer’s The Year’s Midnight locates your eyes on the screen and eerily overlays then with plumes of smoke. Chris Milk’s The Treachery of Sanctuary (the piece the Barbican has chosen to lead with on most of its marketing material) tracks the viewer and transforms their reflection into a huge winged creature. Here the Barbican and Google have collaborated to commission a series of new works specially for the exhibition, including installations by Karsten Schmidt, Zach Lieberman and duo Varvara Guljajeva and Mar Canet.

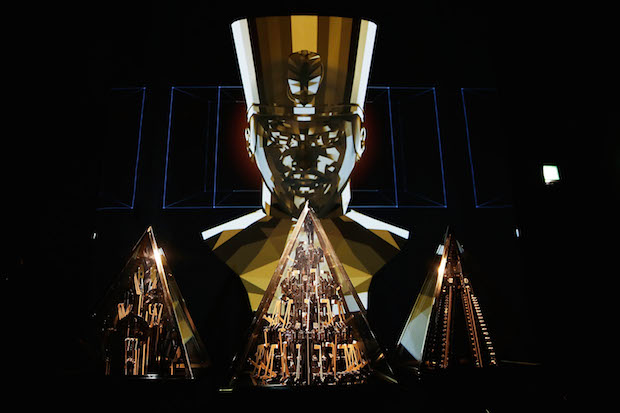

Elsewhere in the Barbican, there are other works to explore. In the entrance, Universal Everything has created Together, a crowd-sourced animation project which allows visitors to create and submit short animated films. Minimaform’s Petting Zoo invites you to play with giant robotic snakes and, for the more gaming-orientated, the foyer hosts a large cage dedicated to Indie Games, featuring work my developers Jeff Minter, Phil Fish and Jenova Chen. Down in the Pit Theatre, Umbrellium have taken over the entire space with their work Assemblance, a landscape of lasers where human interactions, such as holding hands around a light sources, trigger quirks of the environment like the sudden appearance of bubbles or smoke rings from the ceiling. Participants must experiment to work out what does what, leading to a jovial and collaborative atmosphere.

With a strong combination of playfulness and interactivity, this exhibition is sure to be a crowd-pleaser. Although the pace seems at times quite uneven, the more regimented initial section is a successful base for building the themes of the later work, as well as proving just far digital technology has come. How many people will make it to Bloomberg SPACE to see Marshmallow Laser Feasts charming Forest I’m not sure, but on the whole the disparate nature of the works, spread about the entire Barbican Centre, give the entire building a sense of buzz and excitement. Digital Revolution is a good example of what the Barbican does well – ground-breaking, informative exhibitions that don’t forget the importance of having fun.

Digital Revolution

Barbican Centre, London

Until 14 September

barbican.org.uk/digitalrevolution