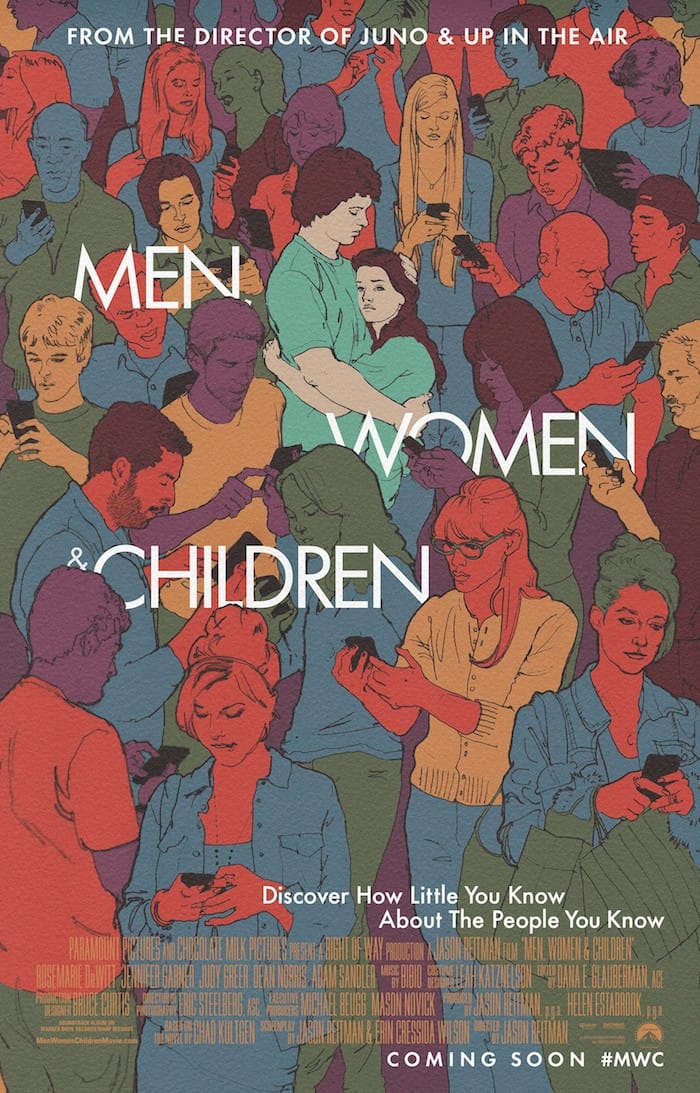

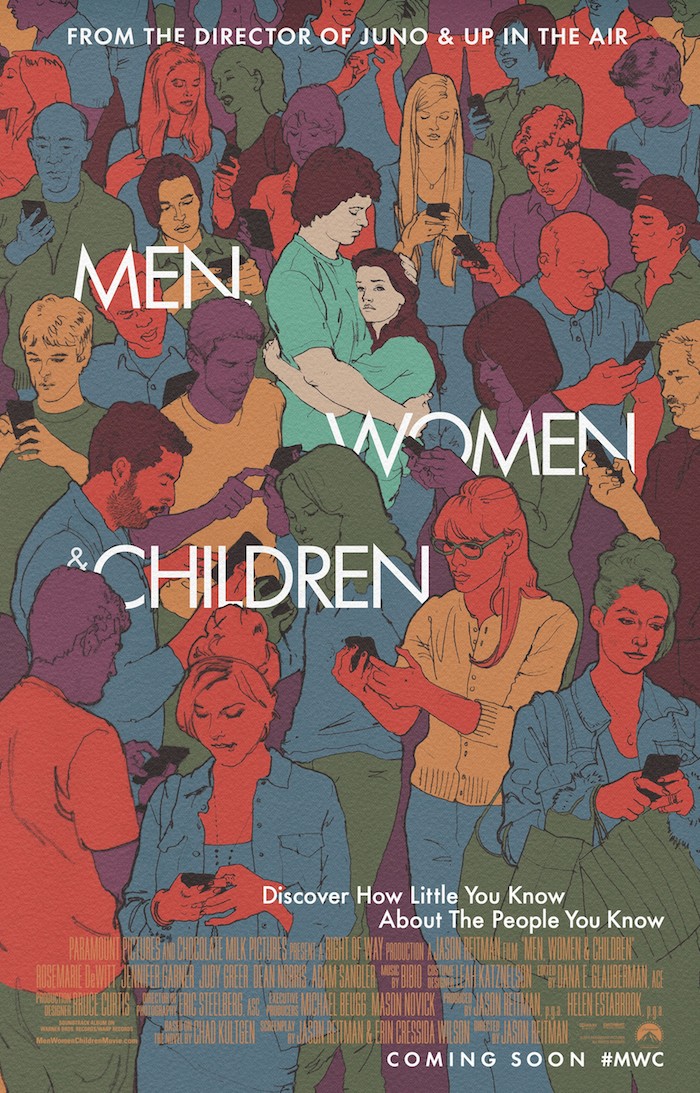

The problem of portraying screen-based interactions was a real design headache for Jason Reitman's latest movie, on the topic of social media. Luckily, specialist studio Smith & Lee had the answer.

What was the initial brief that you were approached with?

Jason Reitman, the director of Men, Women and Children, visited us while we were working on another film, Draft Day; he told us he was working on a project that had a lot of onscreen interactions that were vital to the storytelling. He was interested in treating the movie screen like the desktop of a computer – not as if we were looking through a translucent surface – but simply overlaying the graphics, text, cursors, etc.

He wanted to allow the audience to watch the actors’ performances at the same time as watching their onscreen interactions. Until recently, this would usually consist of an insert shot of a computer screen (or smartphone), then a cut to the actor’s reaction. But audiences are now accustomed to engaging in dense graphic environments, and can process both images simultaneously. It seemed more economical and elegant to avoid traditional screen insert shots considering the amount of graphics in this film.