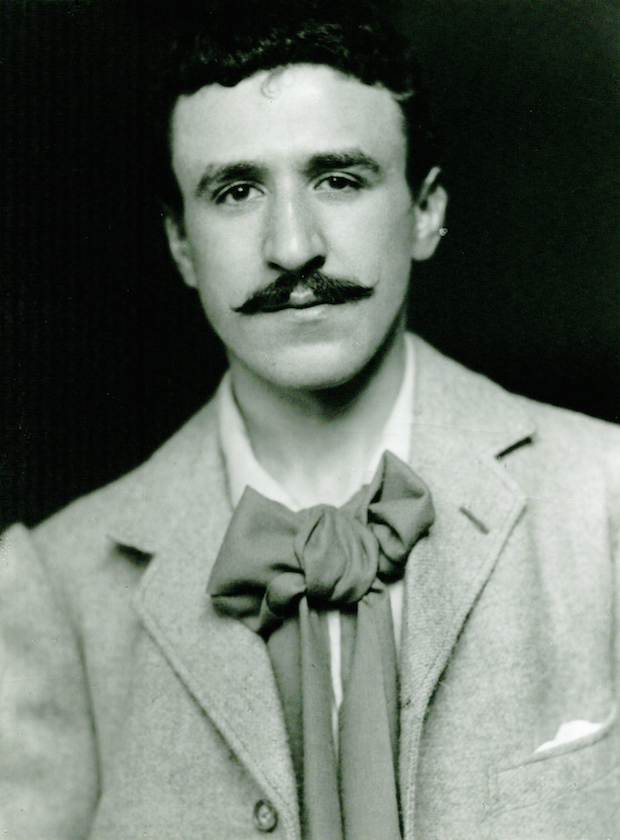

A show at the Royal Institute of British Architects on renowned Scottish architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh throws fresh light on to an important force in the development of Modern architecture.

The Royal Institute of British Architects has a new show on in their imposing 1930s building and it has chosen a fascinating and topical subject: the work of Scottish architect, artist and designer, Charles Rennie Mackintosh (1868 – 1928).

Mackintosh, who is most commonly known for the Glasgow School of Art building which he started designing at the tender age of 29, is certainly in the public consciousness at the moment after fire tragically took hold of the Mackintosh building last year. While the fire destroyed one of the masterpieces of British interior architecture, the wooden Mackintosh Library, the building as a whole was thankfully saved.

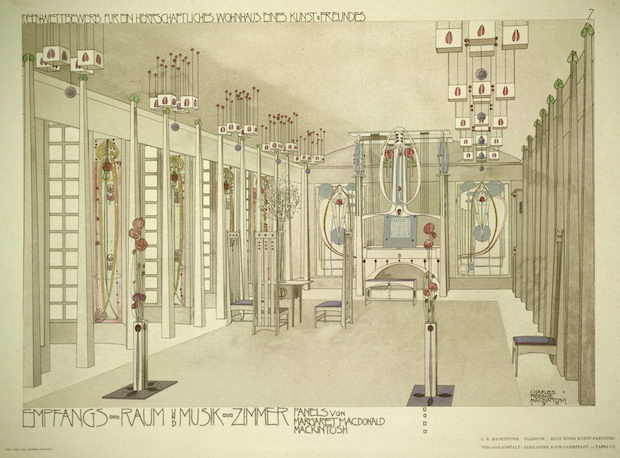

Mackintosh’s works are seen as some of the only truly radical early twentieth century pieces of architecture to emerge from British soil. They represent one of the few occasions where avant-garde designers from the continent looked to Britain (or Scotland, at any rate) for inspiration. Mackintosh and his wife, fellow artist Margaret Macdonald, had their work on show at a Vienna Secession exhibition in 1900. The influence on the Viennese modernists is all too clear, particularly in the use of stylised Rose motifs and Japanese-inspired restraint when compared to Belgian and French Art Nouveau movements.

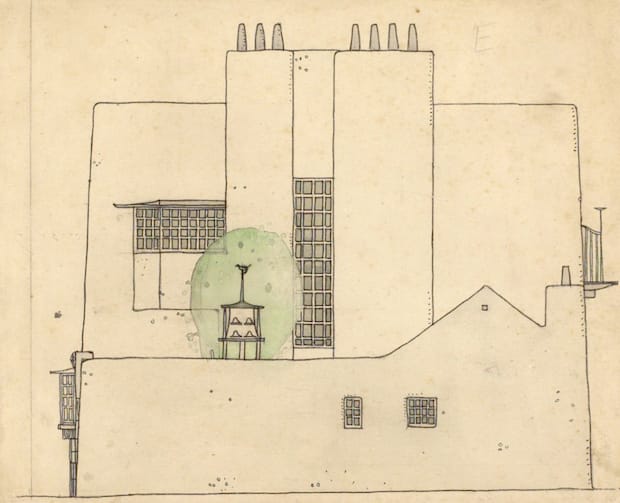

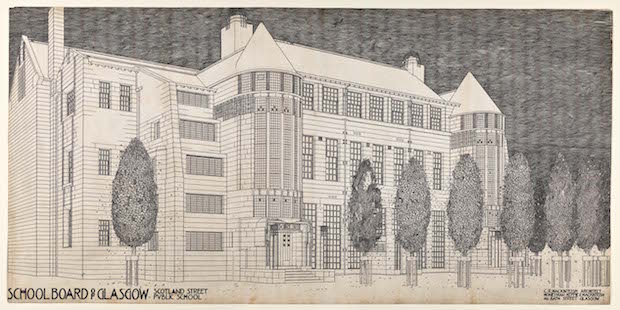

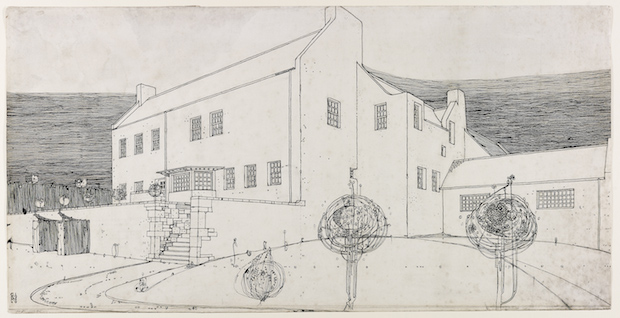

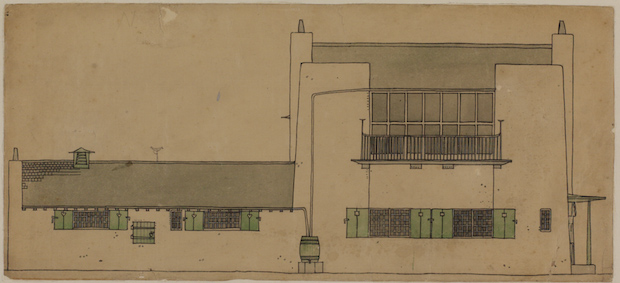

The RIBA show, Mackintosh Architecture, which is the result of a four year research project led by Dr Pamela Robertson, is a well-timed opportunity to reconsider the work of this great architect and his cultural importance. While sadly not many of Mackintosh’s buildings were ever built, this show promises not only to allow you to see Mackintosh’s original vision for his realised projects, such as the Daily Record Building, but also what could have been – elegant plans, models and sketches for groundbreaking buildings that never were.

From the sixty plus original drawings, watercolours and perspectives on display in the exhibition, Mackintosh’s skill as a draughtsman particularly stands out; some of the images here combining the accuracy of a technical drawing with the beauty of an artist’s sketch. While for the connoisseur of typography there are wonderful examples of Mackintosh’s unique style of Art Nouveau lettering adorning many of his architectural plans. Architecturally, the elegance and simplicity of Mackintosh’s designs still startle, more lean than the English Arts & Crafts buildings, more humane than what would follow on the continent. It is interesting to wonder what effect Mackintosh would have had on the English cultural psyche if he had been successful in getting some of his designs for buildings in London built.

What’s shocking is that this is only the first exhibition to be devoted to Mackintosh’s architecture and, in light of that, his even greater anonymity as a painter, the area he moved in to in later life. One or two of his wonderful botanical paintings from his time in Suffolk, or landscapes from when he lived in France would not have gone amiss in this exhibition, as a contextualising bookend to his architectural practice.

With some luck, this detailed, timely exhibition will be a spur to more interest in a supremely talented artist, designer and architect. The time he was briefly arrested under suspicion of being a German spy while living in England during World War One could become a sad analogy of the English cultural approach towards Mackintosh otherwise.

Mackintosh Architecture

18 February – 23 May 2015

Architecture Gallery, RIBA

architecture.com