It's found in editing suites, broadcasting houses and radio stations, but you can't buy it or listen to it on Spotify. Here aficionado and avid collector Jonny Trunk reveals the many and varied pleasures of Library Music.

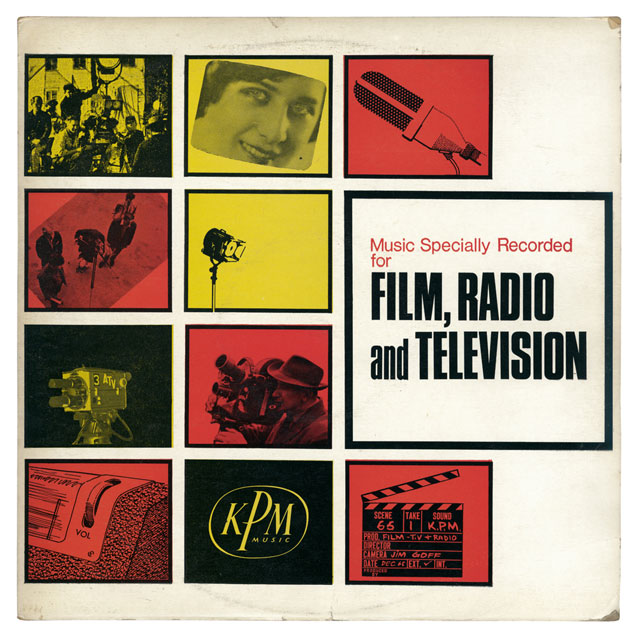

Library music is unlike any other music. It doesn’t sound like any other music and it doesn’t look like other music. Library music is music made for economic use in film and TV advertising: it’s cheaper than employing a composer. It’s found in editing suites, broadcasting houses, production companies and radio stations. It isn’t for sale in shops or available to the general public.

I grew up in the 1970s. A decade of fine, progressive and sometimes experimental youth television. The kind of television that used large quantities of library music to keep costs down. The scatty opening theme to Vision On is library music. The theme to Grange Hill is library music. Most of the music you remember from those spooky public information films is library music. I was never into pop or rock, I liked television music, so it was only a matter of time before I came across library music. My first physical encounter with a library record was back in the early 1990s. It came at a time when I was getting into the music played on late night Open University shows and science broadcasts. But I had no idea how to get hold of it, and no one knew what I was talking about.

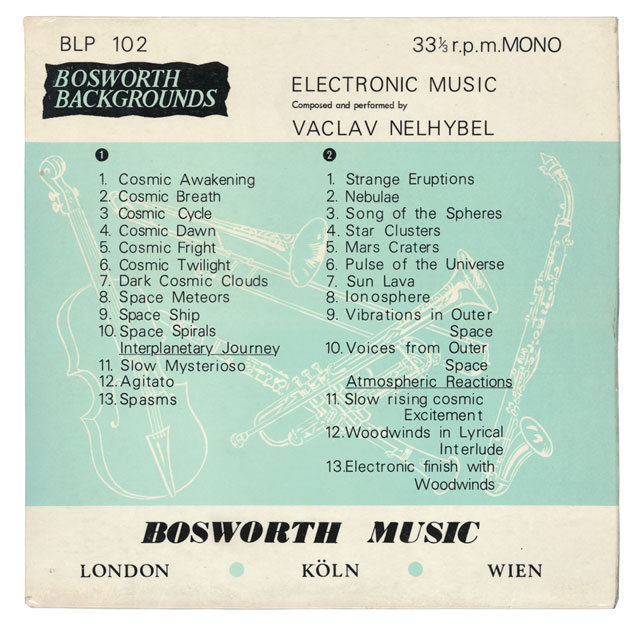

Finding my first library LP was a strange epiphany. It was in a second hand shop in Soho, and the LP was called Dramatics Background. For a start the title had the singular and plural all mixed up. Then the track listing was on the front, with titles like Amoebae, Undersea and Mechanised Electrons. Floating behind the track listing were some very average drawings of a trumpet, cello and a clarinet, there was no artist’s picture. It was all very odd – like a bad education record or something. But the sound was exactly what I was after – a kind of science meets pleasant music.

I needed to find out more, so I phoned Bosworths, the company that produced it, and asked if I could see them. They were based in Heddon Street, just off Regents Street. Howard Friend (the old man in charge) welcomed me into their very dusty world, giving me a potted history of library music and its usage. Its origins go back to the turn of the 20th Century, but its golden age really began in the 1960s when a handful of established London-based companies regularly produced albums of light orchestral and classically influenced music, supplying the BBC and its competitors.

As television expanded and got more exciting throughout the 1960s, so did library music, venturing into more experimental sounds: jazz, electronics, the avant-garde – even the occasional pop-based instrumental. This blossomed further, as tastes and studio technology developed over the next two decades. Then CDs arrived – for anyone into vinyl, that was the end.

The path of a library LP is simple: the musical concept is thought up; the music is then written; recorded; mastered and pressed in very small quantities. It is then sent out or given to broadcasters by reps from the libraries, promoting it as their latest music for sport, industry, comedy, drama – or even for something as yet not dreamt up. Placed well, this music then becomes a recognisable part of our life (for example the theme to Mastermind).

But remember, the music on these original LPs is not for sale, not readily available in shops. It only becomes obtainable when discarded by a production company, donated to charity by a defunct radio station or liberated without permission from the BBC archives. It is very hard to find – in some cases almost impossible – which makes it ever more irresistible and collectable. This is music you are not supposed to have. It’s made for the cutting room, for the edit suite, not for the collector.

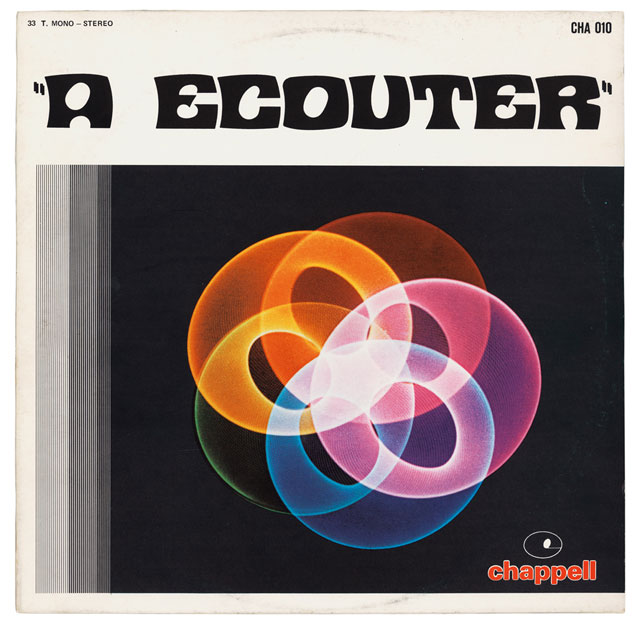

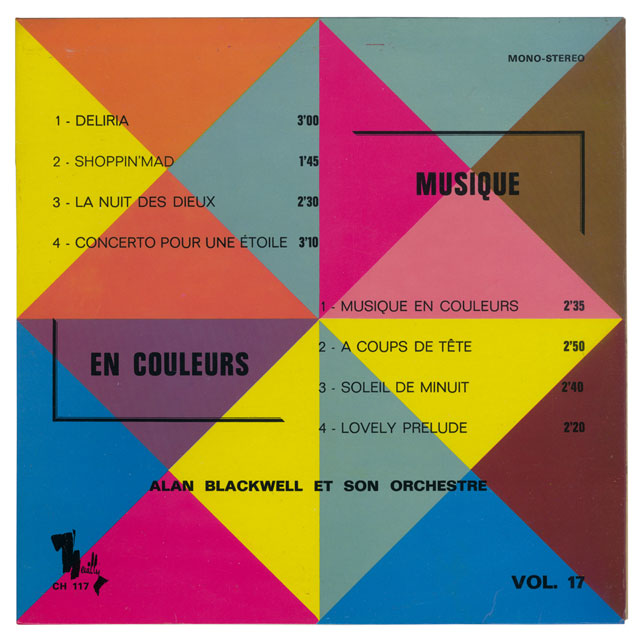

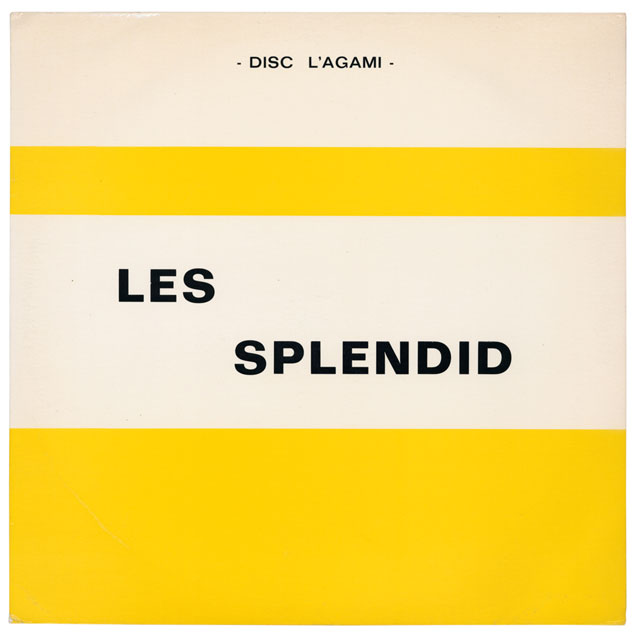

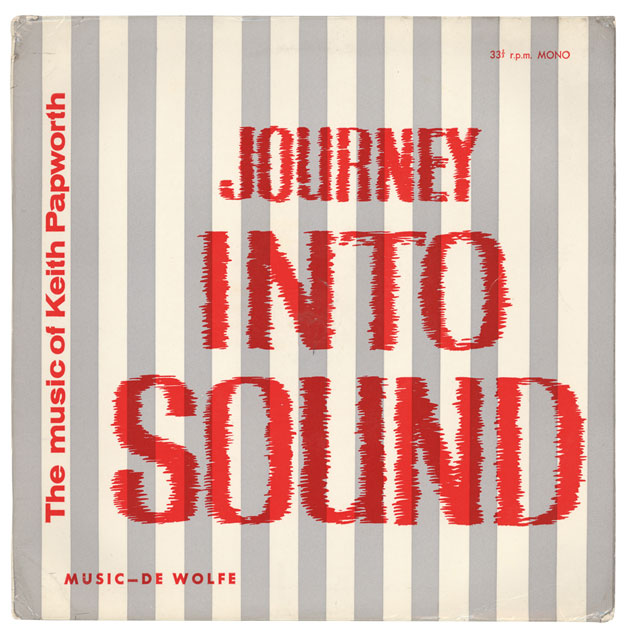

These factors also affect its appearance. Library music does not look like normal music. Several points already touched upon have shaped its aesthetics. It’s music for purpose and function, there are never any pictures of artists or bands. In addition, there were budgetary restraints mixed with a healthy dose of inter-library competition. No one used bright cheerful colours until the Studio G library in Soho opened for business in the late 1960s. Many library companies simply produced their own universal sleeve with a logo front and back, pasting on track listings and recording information with every new release. Some companies (de Wolfe for example) had their own in-house ‘designer’, others kept the same artwork and just changed the LP catalogue numbers and track listings.

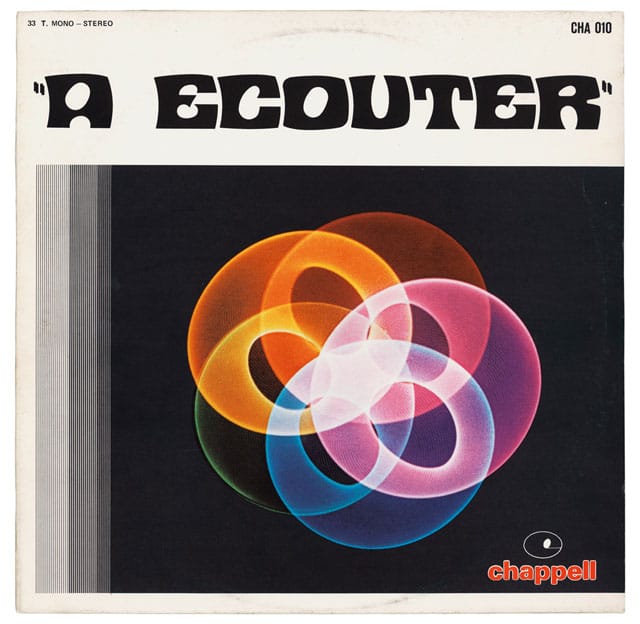

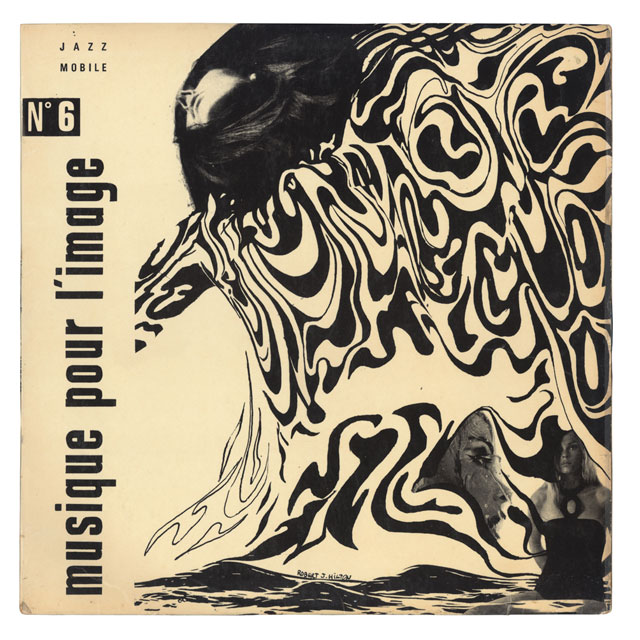

Then in the late 1960s, a few enterprising companies brought library music over from France and Italy, mixing it into the British television market. These countries had their own unique takes on the sound and look of library music, and some odd cross pollinations of ideas, sounds and looks began.

Once I’d found my first library LP I immediately wanted more. But in the mid-1990s there was very little library music information about. I’d meet like-minded collectors in record shops and swap info. Howard from Bosworth helped, but finding the original LPs was very hard. Odd albums would appear on the market as video companies or film and television companies, consolidated or went digital, disposing of their underused vinyl libraries.

My collection grew through hustling, knocking on doors, getting tip offs, hospital radio, defunct studios, trading, and the occasional lucky break – I managed to get to Yorkshire TV the day it threw out its entire music library. And as my collection grew, so did the obsession with the sound and graphics.

New discoveries would lead to new composers, new noises, and very often a whole new graphic style. Incongruous sleeve concepts were coupled with unexpected visuals. There seems to be no artistic or typographical rules regarding library music sleeves. You get the impression that no one was in charge of sleeve art, or no one was actually looking. Perhaps the people from the libraries considered the sleeves not as important as the music. Whatever the reason, the sleeves are a profound influence to those who appreciate them.

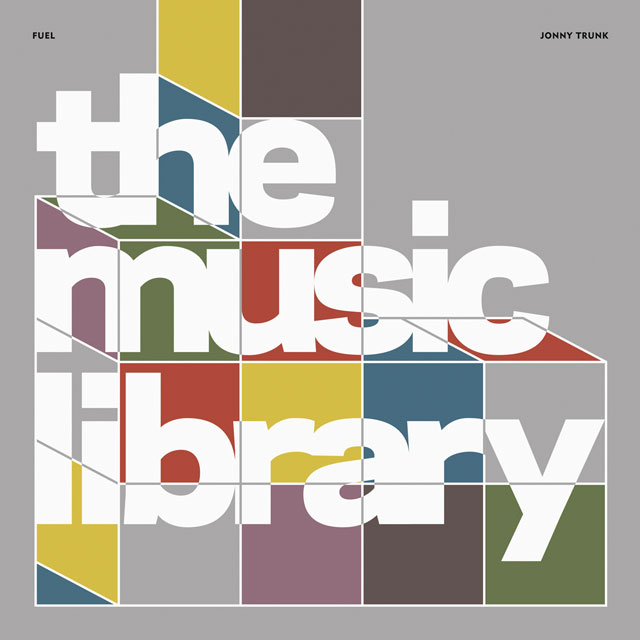

By 2004 I’d re-issued old and quite odd library music on vinyl, met loads of like- minded library collectors and watched as the whole little scene had grown both in the UK and into Europe. Even in America, a country that didn’t really have a particularly interesting home-grown library music heritage, big money was being paid for rare LPs. Some excellent hip-hop was being made using raw library material. I’d also just finished a show in Edinburgh based on letters I’d collected working in soft porn (a whole other story) and got an email from the graphic design company FUEL. They’d started publishing their own books and wanted to make one about the letters I’d collected.

I’d already done a deal with another publisher, but went to see them with a bag full of library LPs. I explained what library music was and that the sleeves were some times raving mad, but graphically interesting and unusual. Within thirty seconds FUEL had agreed to the book. Over the next few months I got together with fellow collectors such as Fraser Moss (from YMC), Julian House, Cherrystones and Jerry Dammers to bring in over 300 sleeves. We pooled information, I wrote up what we knew, and The Music Library was published in 2005. It sold out fast, slowly becoming not just a dazzling and peculiar reference for collectors and graphic geeks, but also having an affect on the value of some of the LPs it featured.

Fast-forward to 2014 with library knowledge and popularity still growing, and the sought-after book now long out of print. FUEL and I agree that an updated and fully expanded book is now needed. What I thought would be a weekend job turned into a six month submersion back into library music. The new edition is twice as large in every respect – twice the sleeves, twice the information, hundreds of times more interesting.

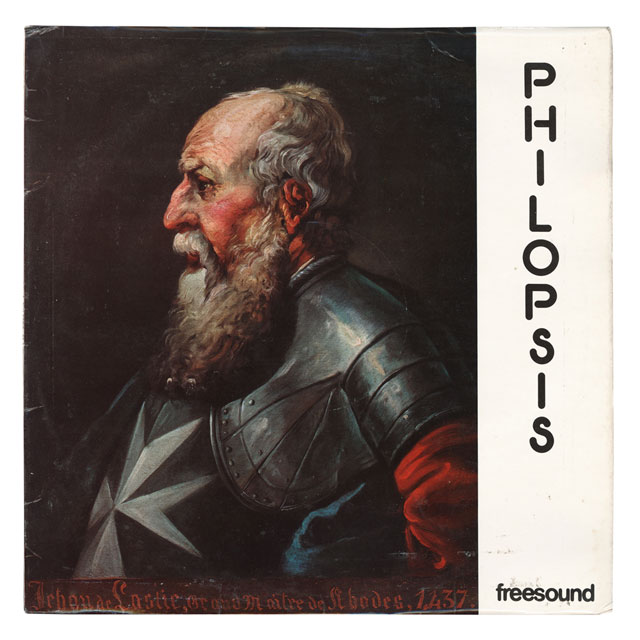

When asked to write up this brief trip into library music it was suggested that I included some favourite sleeves. Old faves would include Philopsis – a sleeve from the French Freesound label. Here an 18th Century portrait meets a 1970s font, with music from another planet. I love many of the de Wolfe ‘paper bag’ style sleeves with their hand drawn or painted lettering over pink and white or grey and white paper bag style stripes – Journey Into Sound is a great example with an exciting hand drawn graphic vibrancy to the letters giving the more unusual musical compositions a more exciting feel.

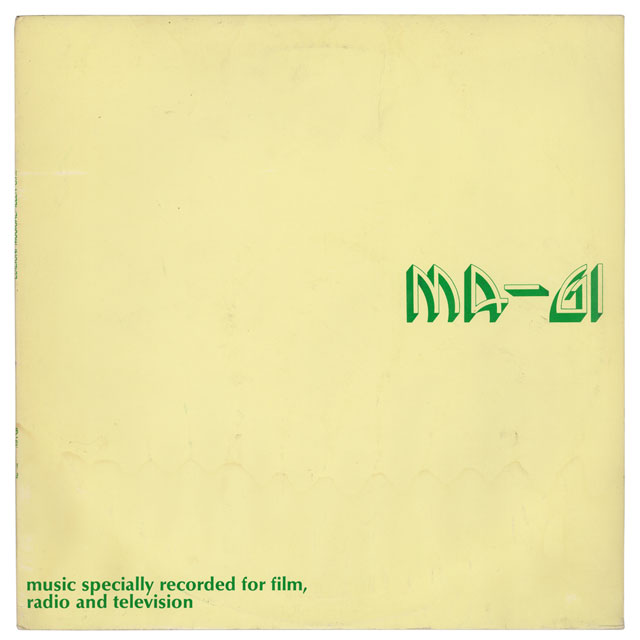

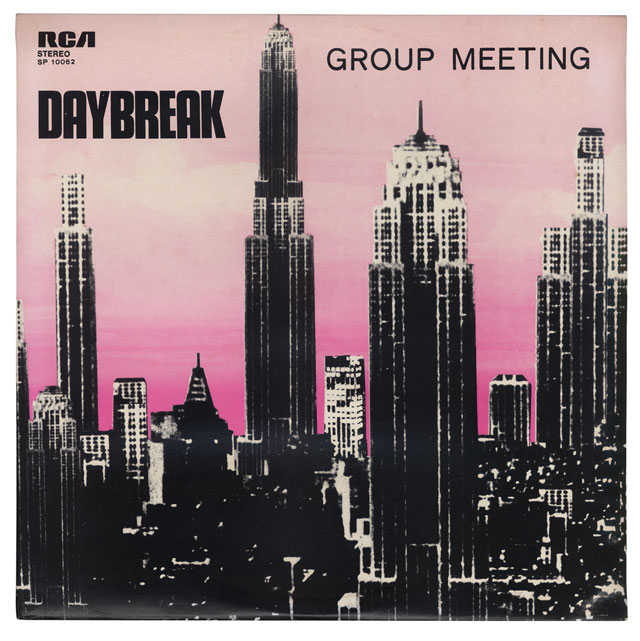

Newer discoveries for this fully expanded edition would include one from the Italian Pinciana label, where the sleeve has nothing but a white circle on an orange ground. There is nothing else. Just nothing. I love MA-GI issued by Iller (an offshoot of the large Italian RCA empire) as I have no idea what is going on or what it means and exactly the same can be said for the music. I adore Group Meeting / Daybreak as I haven’t a clue as to which is the title and who is the artist, and I gaze at the all new Manhattan skyline cut, photocopied, enlarged, reduced and stuck back together again.

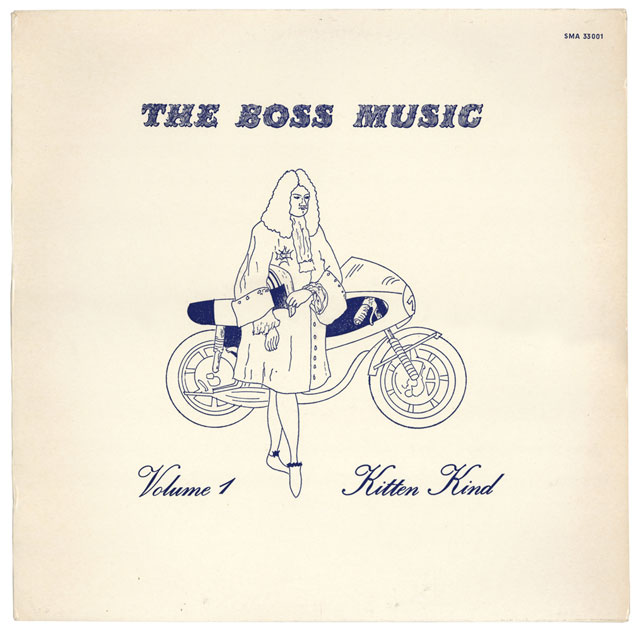

Felt tip is an underused medium, but flourishes in the library field. A fine example is Relax, from a company well aware of mindfulness forty years before it became fashionable. And I should finally point out The Boss Music / Kitten Kind. This was a favourite of FUEL’s from when we made the first book. It’s a slightly naïve drawing of a French male courtesan (from about 1780) standing next to his motorbike. Now if that doesn’t get you revved up about this most bizarre of collecting fields, I don’t know what would.

Jonny Trunk is a writer, broadcaster, collector and label owner at trunkrecords.com.

A revised and expanded edition of Jonny's book The Music Library

featuring over 600 sleeves will be published by FUEL on 7 April 2016. A slipcased edition with a 10” vinyl record featuring rare library music and limited to 500 copies is available exclusively from fuel-design.com