Darkroom’s Rhonda Drakeford marvels at the never-before-seen material in Phaidon’s new tome dedicated to Ettore Sottsass, a book that like the designer’s work is more than the sum of its parts.

Ettore Sottsass has long been a hero of mine — his work and that of the Memphis group are one of the myriad things that inspire the maximalist look of my shop and label, Darkroom. This appreciation was culminated last September in our So Sottsass season that took place during the London Design Festival. It’s no surprise, then, that I already own many books about his work. Each tells the story of a different specialism, and there are many — from his reportage photography, his early experiments with ceramic and enamel, to his interior design, architecture, jewellery, paintings, furniture and machines. I have, however, always felt disappointment and frustration that the design of these books have never done him or his work justice. It was therefore with a mix of excitement and trepidation that I awaited the arrival of this weighty new tome by Phaidon...

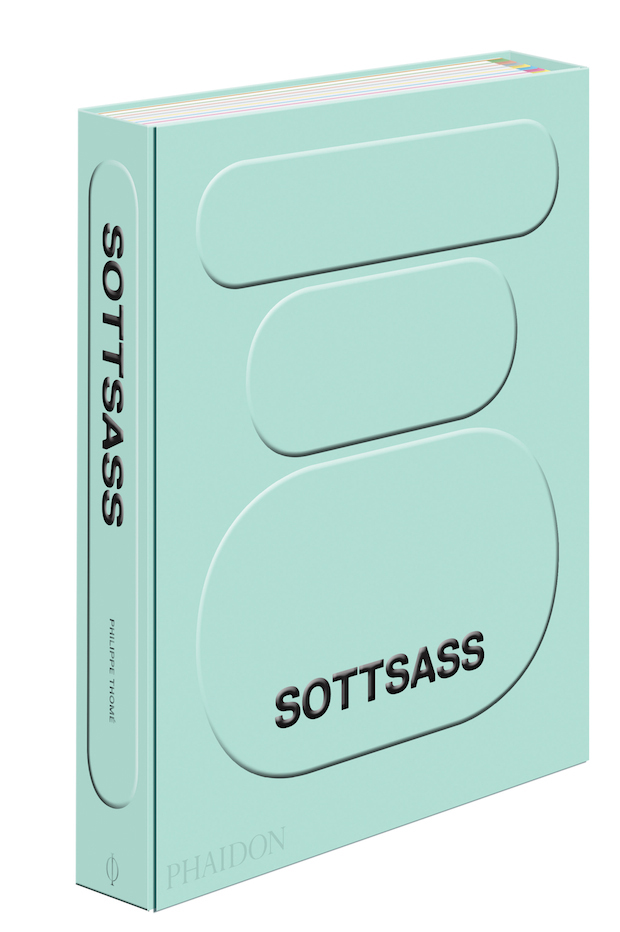

With it’s blind-embossed, hard-back, duck-egg-blue, gate-fold cover, the book is immediately elevated to a striking slab-like object. Upon opening, the black and white striped end papers that extend beyond your peripheral vision really start to quicken the pace of your hopeful heart. And this really sets the scene for the standard of the book’s design (by Julia Hasting). Split into thirty-five bite sized sections with extended tabbed dividers, printed on a variety of paper stocks and page sizes to suit the content, one gets the sense that these pages have been torn from the sketchbooks, family photo albums and archives of Sottsass himself.

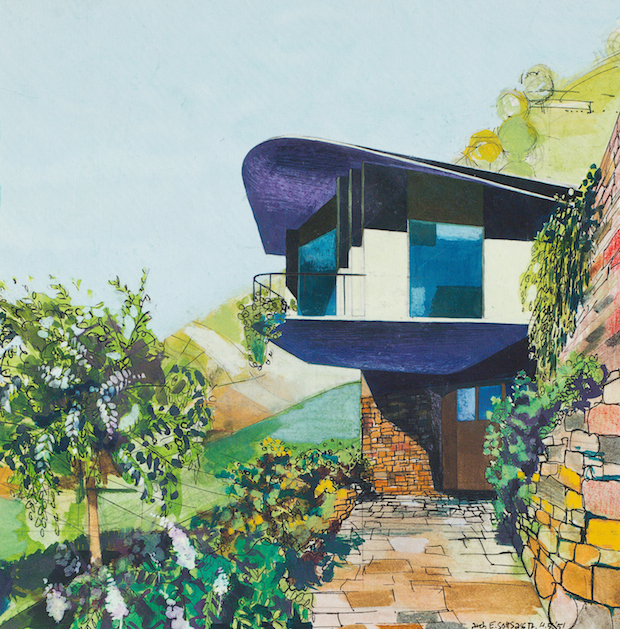

The content is a perfectly balanced mix of writings and imagery. Running throughout is an engaging text by the author Philippe Thomé that chronologically accounts the long and extremely productive life of the designer. It’s this chronological structure that really gives an insight into the journey of his personal life as well as his works over a 90 year life. Spanning a century of immense changes in technology, political and social factors, it is important to acknowledge the context of his productivity. Nowhere is this more poignant than the journey from social housing he worked on in post war Italy to the exclusive beach-side properties of the affluent and indulgent 1980’s. It is also interesting, and ironic in a way, that the limitations of technology had an obvious effect on the type of records available of his early works and travels — black and white photographs are all that exist of a time when the world for Sottsass was starting to open up to colour.

In addition to the backbone texts by Thomé are four enlightening essays by doyens of design commentators; Francesca Picchi, Deyan Sudjic, Emily King and Francesco Zanot. They succinctly describe the many facets of his experimentation, production and collaborations, for Sottsass kept himself busy and at the heart of design theory and practice throughout his life.

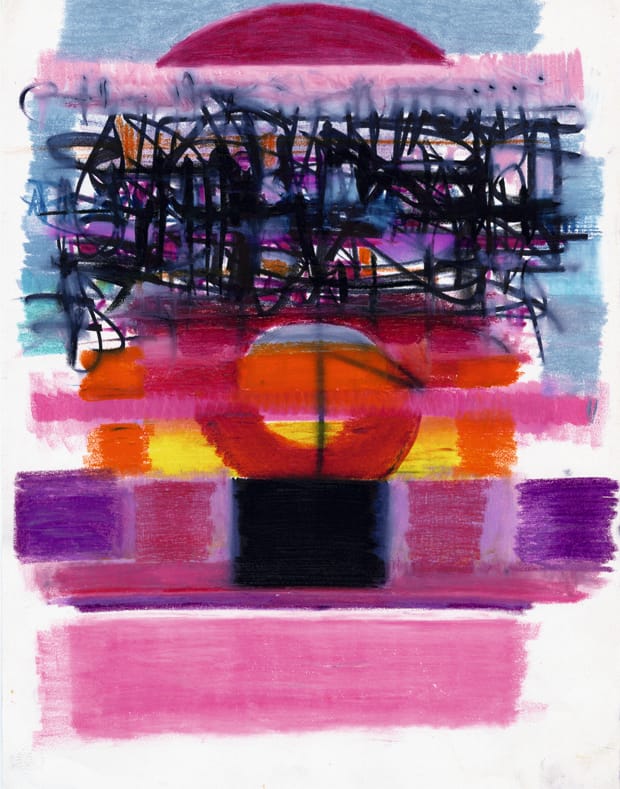

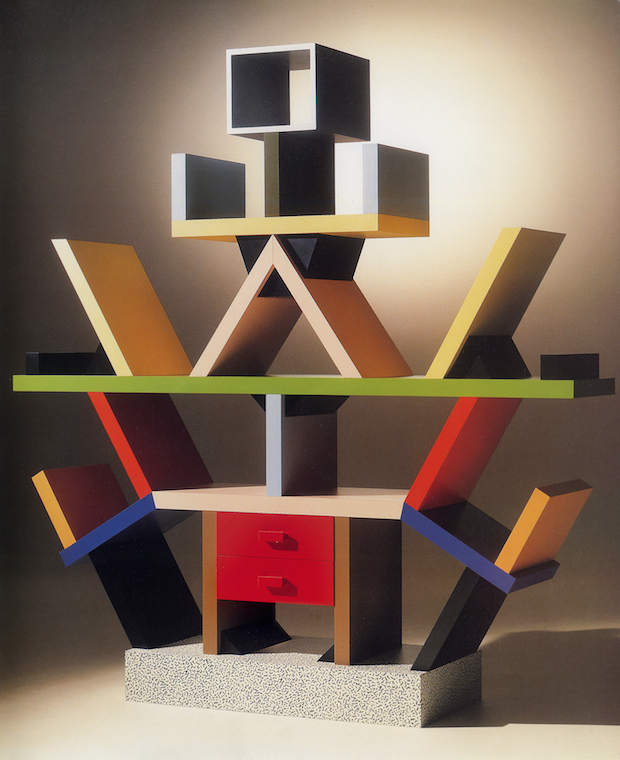

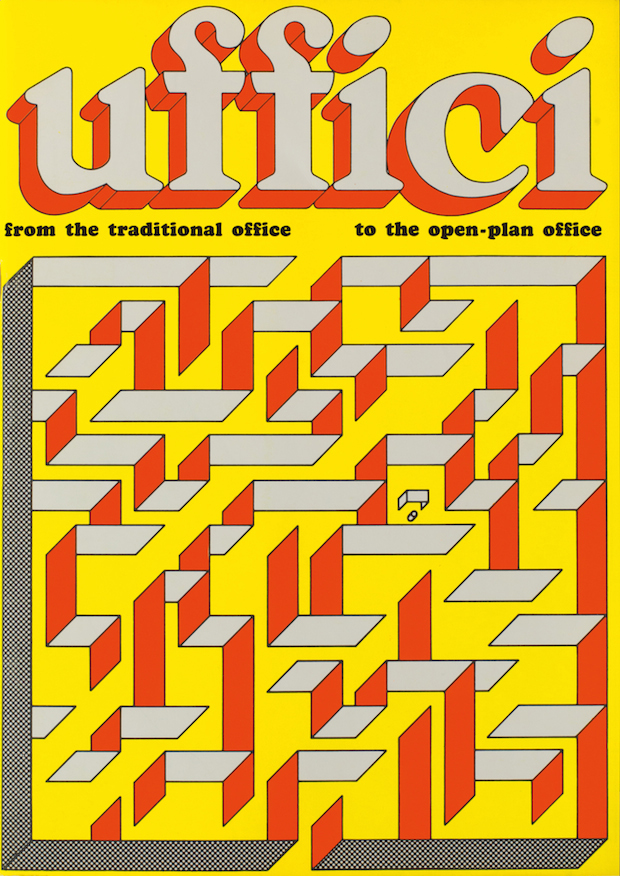

For me though, the plethora of photographs and drawings gathered here from Sottsass’s archive are the most spellbinding. Intimate family photographs, records of indigenous artisans taken whilst traveling the world and snaps depicting him with such luminaries as Picasso, Ernst, Dylon, Ginsberg, Newton and Maplethorpe illustrate his interest in a cross-section of mankind. I turned pages awestruck at the colour plates that record every aspect and stage of his works; initial sketches, through manufacturing, professional advertising shots and the posters, catalogues and invitations that he designed for his multitude of solo and group shows. Many of these spectacular images have never been seen before, and particularly striking are those of his earlier, more cruder works — the period that for me holds the most resonance.

Francesca Picchi observes in her opening essay that Sottsass had a very rigorous view on form — solid, strong and clear. He built things by placing them on top of each other. The quality of his details came from this very system of combining elements together. The book illustrates this principle perfectly. It is the sum of many parts, none of which would perform as well if separated. I will still be reading this book in years to come — it is a joyful, invigorating experience, too much to take in during one session — something I’ve not found in a book since childhood. And, while I surprise myself by saying it, the hefty price tag of £100 for such an epic tribute is wholly justified. Ettore Sottsass by Philippe Thomé

Published by Phaidon

£100.00

phaidon.com