The National Gallery’s latest exhibition uncovers a history of colour production that will be a revelation to those working in today's creative economy.

A recent Kickstarter project claims to have made a tool that has obsessed technologists for the best part of a decade. It is the concept of a colour-picker pen, a real world version of the familiar pipette used across photo editing software to sample and redeploy colours from within a digital image. MIT’s Tangible Media Lab cracked this back in 2004 with their I/O Brush, which captured not only colour but texture and even movement from physical objects before allowing you to ‘paint’ these back onto the screen. However, while impressive, this was still a process that only outputted in pixels. That is the hurdle that this most recent initiative has finally overcome. It is called the Scribble Pen and it will cost £90 for the most advanced version, the one that can reproduce a reported sixteen million colours directly onto paper. It achieves this by mixing ink from five different chambers on the fly, a scan and go system powered by a 16 bit colour sensor and an Arm 9 processor. It does have its limitations of course – based on the CMYK standard, there are areas of the colour field and levels of luminosity that it wont be able to reach. Nonetheless, this pen can be taken to stand for something much larger, an apotheosis in the sheer availability of colour. Anything that is over-supplied sees its affective currency fall. Our relationship to colour has been a attenuated by its ease of appropriation and reproduction, the cataloguing systems that capture this excess and the standards and hex values that identify it. When everything is tryable, applicable and swappable, colour is often reduced to a surface treatment.

Against this development the National Gallery’s latest exhibition, Making Colour, stands in stark historical contrast. The display is an encyclopaedia of the materials used to produce the pigments that artists relied upon for the largest percentage of art’s history and the difficulty of their extraction. Through a series of rooms, each dedicated to a different hue, you are introduced to origin, be that mineral or organic, then process, then exposition in the form of art works drawn from the museum's collection (as well as a few loanees).

Take blue as a case in point. In its rarest form it was once more costly than gold due to the need to hew it from the remote Sar-e-Sang mine of Badakshan, Afghanistan. This rock, lapis lazuli, was powdered to create natural ultramarine, prized across Europe for its depth of colour. The reason the Virgin Mary is most often depicted draped in royal blue is partly because the sheer expense of this pigment made its use a form of devotional offering. In Sassoferrato’s Virgin in Prayer (1640-50), displayed here as exemplar, Mary’s shawl is so iridescent that it seems somehow holographic, hovering off the picture plain and into its own hyperreality: transcendence by means of the colour economy.

For those with shallower pockets, or whose painterly needs called for something more subtle, there were alternatives meaner in both price and shade. Cobalt glass could be ground down to form smalt, a darker blue that degrades heavily over time due to chemical instability. That fact is proved here by Jan Jansz. Treck’s Still Life with a Pewter Flagon and Two Ming Bowls (1651), the porcelain’s decoration having soured to a murky green.Given his use of azurite, Albrecht Altdorfer may have actually desired a slightly greenish tint to the blues in his 1520 painting Christ taking Leave of his Mother, the copper carbonate mineral know for shading towards that part of the spectrum. One of the first synthetically manufactured pigments, Prussian blue, was discovered around the beginning of the 18th century. For the first time it provided artists with a cheap and plentiful supply of the colour, for instance allowing Thomas Gainsborough to enthusiastically daub the trim of the sitter’s dress in Mrs Siddons (1785). Likewise, the chemical synthesis of ultramarine by the Frenchman Jean Baptiste in 1828 meant that this once rarefied paint could be mass-manufactured, reducing its apparent mysticism.

So the exhibition goes, through the red “lakes” squeezed from the bodies of Kermes or Cochineal insects, the verdigris scrapped from copper oxides and the ochres dried out of clay. It tells the story of art as guided by specificities of ecosystem and topography, shows how modes of expression could be restricted or enlivened by vagaries in the weather, or the constriction of international trade routes. This is image-making as an act embedded in specific localities, decidedly of a place and time – it’s a bracing re-education for those working in today’s globalised and digitised world of art and design. We would do well to remember that the creative arts once developed according to the contingency of individual colours.

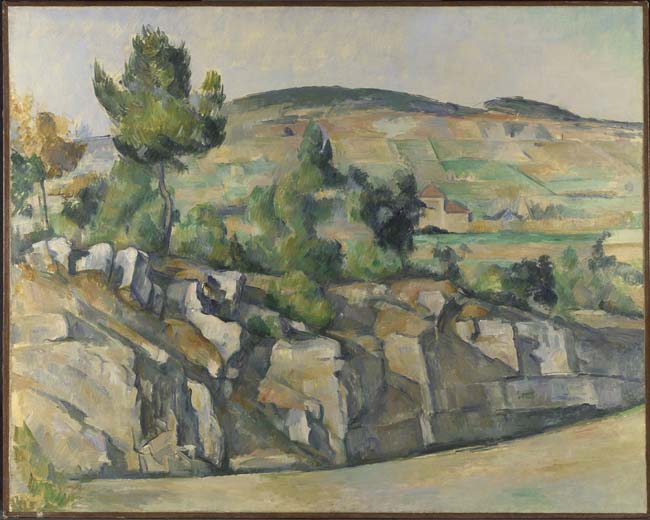

It would be contrarian to say that the profundity brought about by advances in science and technology has simply been detrimental. As Pierre-Auguste Renoir is quoted at the opening of the exhibition: “Without paint in tubes, there would have been no Cezanne, no Monet, no Sisley or Pissarro, nothing of what the journalists were to call impressionism.” No Cezanne… what route would art have taken in the twentieth century if colour had not been productised in the nineteenth? But there is another, related question that Making Colour doesn't extend far enough to ask: what would have happened without paint in cans? As critic David Batchelor relates in Chromophobia, an exposition on modernity and colour, artists in the twentieth century developed an uneasy relationship to paint, especially that which, in all its abundance, was originally intended for the wall but instead found its way to the canvas. Frank Stella claimed to want to keep his paint “as good as it was in the can”, what Batchelor identifies as an “anxiety that the materials of the modern world might be more interesting than anything that could be done with them in a studio, and the more you did to them the less interesting they might become.” From that perspective, the reduction to surface treatment becomes something of a coping mechanism, a deflationary tactic.

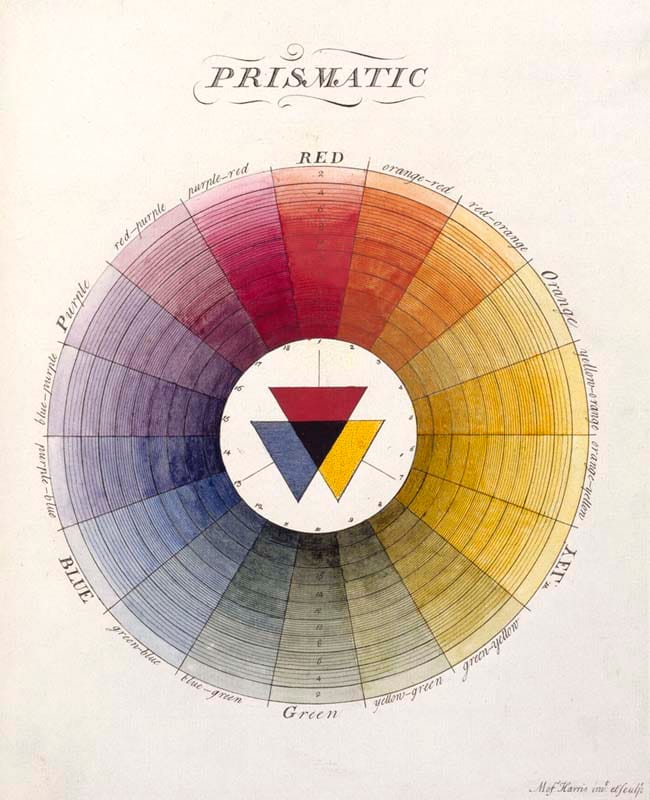

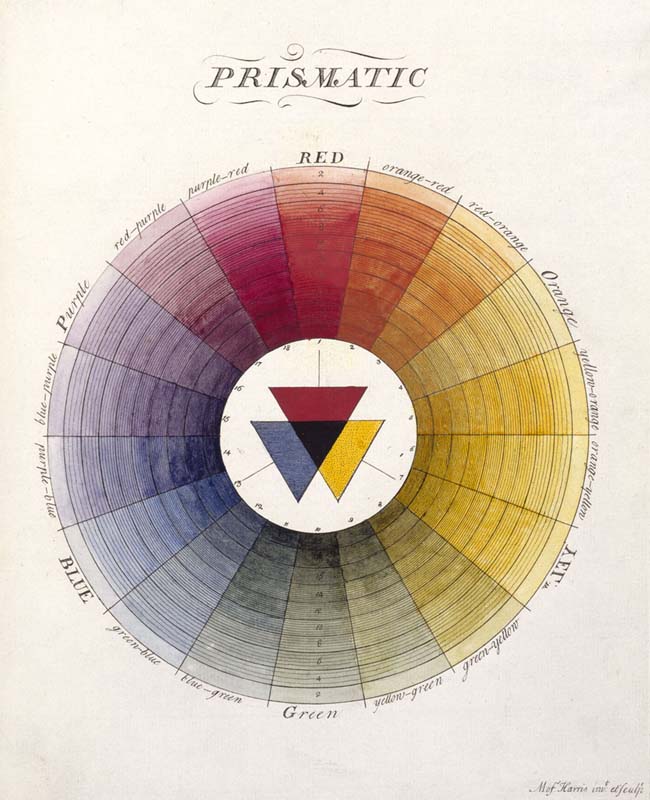

The reverse movement, a seepage from the canvas outwards, has been just as troublesome. One of Stella’s contemporaries, Yves Klein, would certainly attest to that. Klein’s legacy is written in his patented International Klein Blue, a colour that owes its intensity to the predominance of ultramarine in its make-up. Its invention would doubtless have been precluded if a man-made version of the pigment had not been discovered. The artist couldn't have guessed quite how “international” his namesake would become, the colour now ubiquitous across so many products and applications (with graphic designers being the worst offenders) that it has lost all its chromatic allure. One place it won’t be found, however, is appearing from the end of a Scribble Pen. CMYK can’t approximate IKB. Nor can a screen. There are thankfully still some limitations on how far a colour can spread; after all, a basic tenet of colour theory is that when all the primary colours are mixed together, they appear as black. Making Colour

18 June – 7 September 2014

The National Gallery, London

nationalgallery.org.uk