Artist’s books provide a sheltered proving ground for new ideas and unestablished artists. The Museum of Modern Art’s bibliographer David Senior chooses five of the most foundational.

Here are five titles from where I work at the Museum of Modern Art Library. I collect new books for the collection and I often present the existing collection through exhibitions, classes, lectures and assisting visiting researchers. The collection itself is a pretty thrilling testament to the various ways avant-garde art and design practices used the format of the book or magazine to formulate new ideas and transmit these ideas across space to new audiences through little publications.

We can think of these books here as a small pile, like the piles of books that invariably accumulate around my desk during a day. This piling suits my taste. I like the idea of accumulation and the strange connections that can arise from unintentional groupings of books. They can tell a story or create a weird sentence. I also think that this is how thought works: resembling a pile of books where words and images mingle and bounce off each other so as to create little messages and subtle truths.

Album Primo-Avrilesque

This is Alphonse Allais' unassuming little portfolio, Album Primo-Avrilesque or the April Fool's Day Album. Allais was a popular writer and humorist in Paris in the late 19th century. He was a regular around cabarets in Montmatre and hung with an interesting crowd, the musician Erik Satie being one notable friend. Allais is known for having given Satie the nickname “Esoterik" Satie. This portfolio was published several years after Allais’ participation in a couple salon exhibitions called Salon des Arts Incoherents in Paris in 1883 and 1884. In these salons, Allais first showed his monochrome compositions that would later appear in this portfolio. The first section of portfolio contained these monochromes and their titles completed the work:

Blue composition – The awe of the young naval French recruits on perceiving for the first time the blue of Mediterranean.

Green – Some young men known as greenbacks on their bellies in the grass drinking absinthe.

White – First Communion of Anaemic Young Girls in the Snow

Red – Apoplectic cardinals picking tomatoes by the shore of the Red Sea.

The second half of the portfolio contained a curious musical score – a funeral march entitled Funeral of a Great Deaf Man. The score is blank, completely blank. The gesture is outrageously funny and also, it is hard not to think of it prefiguring an essential gesture of avant-garde musical scores of the 20th century,

most obviously a work like John Cage’s 4’33”.

Fuck You

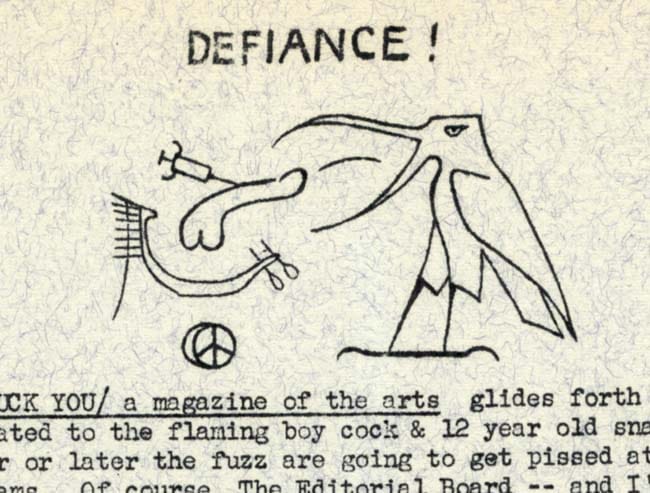

Fuck You – A magazine of the Arts

was first published in February 1962 in "a secret location in the lower east side." Ed Sanders was the editor responsible for Fuck You and also the drawings on many of the covers and pages of the magazine. The little poetry and art magazine was an elaborate attempt to run-up against decency laws in New York, to promote Sander's radical pacifism and anarchic cultural vision. Borrowing from William Burroughs, Sanders used the phrase – "total assault on culture" – as a declarative subtitle for his issues of Fuck You and his working philosophy of writing, performing and publishing. The general ethic of the project prefigures a bit the language and sentiment of the protest movements in the US of the sixties as well as the cultural revolution of the "drop-outs" and their sex, drugs and rock ’n' roll. He printed them himself on a mimeograph machine, first in the offices of the Catholic Worker, and then in Sanders' apartment after he was able to buy his own mimeograph machine.

Fuck You is often grouped together with a whole generation of publications being produced in New York at that time – labeled the Mimeograph Revolution – with most of these little magazines documenting the work of New York School poets and other counterculture luminaries like Burroughs, Ted Berrigan, Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso, John Ashberry, Joe Brainard, Andy Warhol etc. Sanders reiterated his working editorial principle, "I'll print anything!”, in each issue of Fuck You and the overall tone reflected his equally humorous and radical disposition towards his publishing project. The content of Fuck You, with its overt use of profanity, the embrace of a sexual revolution (“Fuck for Peace!” was a common slogan) and anti-authority screeds set it apart from the other little mimeograph poetry magazines. These aspects created attention for the publication within the downtown scene as well as the attention of the police and FBI. On several occasions, Sanders' apartment and studio and later, Peace-Eye bookstore, were harassed and raided by the police and materials were confiscated. Despite these challenges, Sanders continued his publishing project until the late sixties, when he grew more active with his rock band The Fugs.

Tragediji jedne venere

In Tragediji jedne venere/Tragedy of a Venus (1976), Croatian artist Sanja Iveković used the images and text from a tabloid story of Marilyn Monroe's life. On the opposite pages are reproduced snapshots from the artist's personal collection of photos. The images share the text description from the tabloid article. Iveković found images of herself that somehow matched the gesture and sentiment of each Monroe image. By inserting herself alongside this Hollywood composite of fame, beauty, and tragic circumstances, Iveković simultaneously impersonates the Monroe story, distances herself from it, and plays with this ambiguity of the interplay between popular media images and personal narratives.

In de Krant

Dutch artist Hans Eijkelboom made In de Krant (In the paper) in 1978. As it states on the opening page, the artist tried to appear in his local newspaper in a town in the Netherlands (Arnheim) for ten consecutive days. The performance of the book is to reproduce the newspaper pages in which he appeared. Each page creates the scenario where you search for the artist in the picture, embedded in the landscape — a long-hair, slightly disheveled witness to town activities.

LTTR

In talking about an idea of the productive space of publishing, LTTR (2002-2006) is a work that I always present to visiting student groups. To me, it is a superb example of a group of young artists seizing on the medium as a tool for extended collaboration and opening up a space for artistic practice.

The artists/editors were originally K8 Hardy, Emily Roysdon, and Ginger Brooks Takahashi. Ulrike Müller joined for the last few issues and Lanka Tattersall was a co-editor of issue four. They were young women artists and writers who were focused on fostering content from a feminist and gender-queer perspective. In their own words LTTR was “dedicated to highlighting the work of radical communities whose goals are sustainable change, queer pleasure, and critical feminist productivity.” The production of the journal took on new forms and formats with each number. The journal’s run during 2002–2006 was an activity that simultaneously documented and invigorated a community of artists and writers in New York city at this time. It published works by the editors as well as early works by artists and writers such as Leidy Churchman, Lauren Cornell, Tara Mateik, JD Samson, Klara Liden, Matt Wolf, Wu Tsang, Wynne Greenwood, Pauline Boudry, Andrea Geyer, and Sharon Hayes. Printing and collating early issues was a group event, with many hands working on press and in assembling the journal and its inserts.

As the journal progressed LTTR had an impact outside New York, linking a global community of participants and readers. The project drew in new allies from an international audience. A clear success of the project was how it created connections that would not have existed without the instigation of the journal. Another pronounced aspect of the activities of LTTR was the degree to which each publication also became a performance. The collaborators arranged events, concerts, readings, and discussions throughout the period that they produced the journal. For each of the editors LTTR represented a beginning moment in her art career. In a recent discussion, Emily Roysdon mentioned to me that the experience with the journal was "how I grew up in New York [as a young artist]”.

When the spaces of cities—and I’m thinking here specifically of New York—become less hospitable in terms of prohibitively high rents, and when one faces the prospect of navigating the cold business of the art world, the platform of a publication provides a multifaceted and quite useful creative shelter. It can, for one, help remedy the fraught proposition of showing one’s work and managing a space to collaborate with others. As with LTTR, there is a possibility to foster content that is underrepresented in the conventional spaces for viewing art.