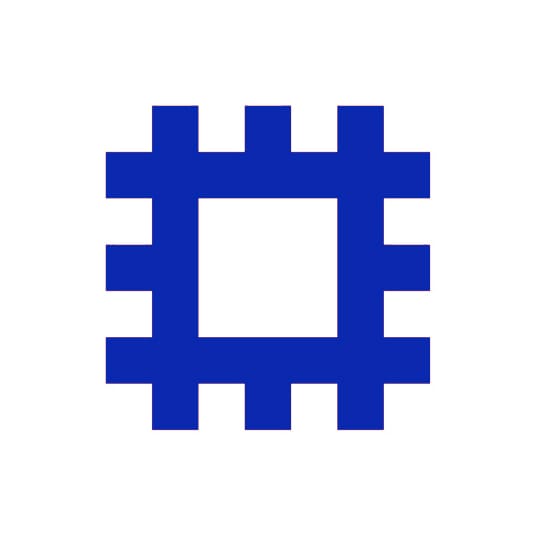

Evocative and memorable, English Heritage’s versatile symbol perfectly conjures up a wealth of pre-historic henges, fortifications and castles, argues Lloyd Northover founder John Lloyd. All over England you can find a symbol that is a perfect visual expression of the subject it represents. English Heritage is the British Government’s statutory adviser on the historic environment. It lists buildings and monuments that it decrees should be preserved, and it protects and maintains more than 400 historic sites that are open to the public. The English Heritage symbol was adopted in 1984 when the organisation came into being. It functions as a corporate marque and as a sign to indicate the locations of the historic properties in its care.

In England, there is another great protector of the historic built environment — the National Trust — but whereas the emphasis of the National Trust’s work is on historic houses and gardens, English Heritage concentrates on more ancient works: pre-historic henges, hill forts, stone circles, Roman archaeological sites, monuments, abbeys, monasteries, priories, fortifications and castles. And this difference in emphasis is clearly reflected by the English Heritage symbol. It suggests the plan of an ancient building with the buttresses shown as square protrusions around the exterior; or the surrounding notches may recall the robust battlements and crenellations of a defensive structure. It is also possible to see four capital letter Es facing right, left, up, and down, to create an enclosure. I am not sure if this last effect is intentional, or a happy accident, but, once you know the Es are there, you cannot ignore them.

When used as a corporate device, the symbol appears in red and when used on traffic signs it is shown in white on a brown ground. It also features on the famous blue plaques that English Heritage applies to buildings with connections to significant persons or events.

I have long been an admirer of this ubiquitous symbol; it is a fine piece of public information design and it meets the necessary criteria for being an effective icon. It is distinctive, evocative, simple, easy to use, legible, and memorable. I would like to give credit to its creator but I have been unable to discover who designed it.

One of the measures I use when evaluating a symbol is to ask myself if I would like to have been its creator. This is one that I would definitely be proud to have in my own portfolio.

johnlloyd.uk.com

Blue Plaques

London’s Blue Plaque scheme was founded in 1866, and is thought to be one of the oldest projects of its kind in the world. It was taken over by English Heritage in 1986, but was previously managed by the (Royal) Society of Arts, the London County Council and the Greater London Council. The first commemorated the birthplace of Lord Byron, on a property in Holles Street, near Cavendish Square, which was later demolished in 1889. The plaques themselves are handmade and can take up to two months to produce. New additions are considered three times a year by a panel that includes Barbican managing director Sir Nicholas Kenyon, poet Andrew Motion and Professor Brian Cox.

Lloyd Northover

If you’ve ever been to a railway station in London then it’s likely that you’ll have encountered Lloyd Northover’s work. The consultancy, which was founded by John Lloyd and Jim Northover in 1975, created the wayfinding and signage for Railtrack in 1999, including a set of beautiful but now hard-to-find pictograms for fourteen of the capital’s stations. Other landmark projects include rebranding Plymouth, creating an online presence for the Design Council and The Royal Navy, and developing the identity for much-loved retailer John Lewis.

April 22, 2014 2 minutes read

Past Signs

Evocative and memorable, English Heritage’s versatile symbol perfectly conjures up a wealth of pre-historic henges, fortifications and castles, argues Lloyd Northover founder John Lloyd.