Laurence King’s compendium, Walk the Line - The Art of Drawing, proves that the draughtsman’s skills have lost none of their relevance.

The action of taking a pencil, shaping the end into a point, placing it onto a sheet of paper and pushing forward into the substrate now has an altered, almost subversive tenor. Drawing takes on a new fascination in a world dominated by frictionless streams of digital imagery. This shift in perspective has attracted a new generation of mark makers, keen to graft this most universal of techniques onto the not always welcoming surface of the art gallery wall.

As the editors of Walk the Line, Marc Valli and Ana Ibarra, state in their preface: “The drawn line is the most direct connection between the sensory apparatus of the artist and the world of representation”. It’s that quality of directness that feels most persistent in the selection of artists gathered here in representation of contemporary drawing practices, a clarity of intention that translates into forcefully realised political, emotional or sexual statements. If drawing might traditionally have been associated with the hurriedness of the preparatory sketch or the frigid impersonality of the “study”, it appears that today, artists who choose the simplicity of the medium are using in ever more complex fashion, working with ambition in terms scale, detail and concept beyond traditional boundaries.

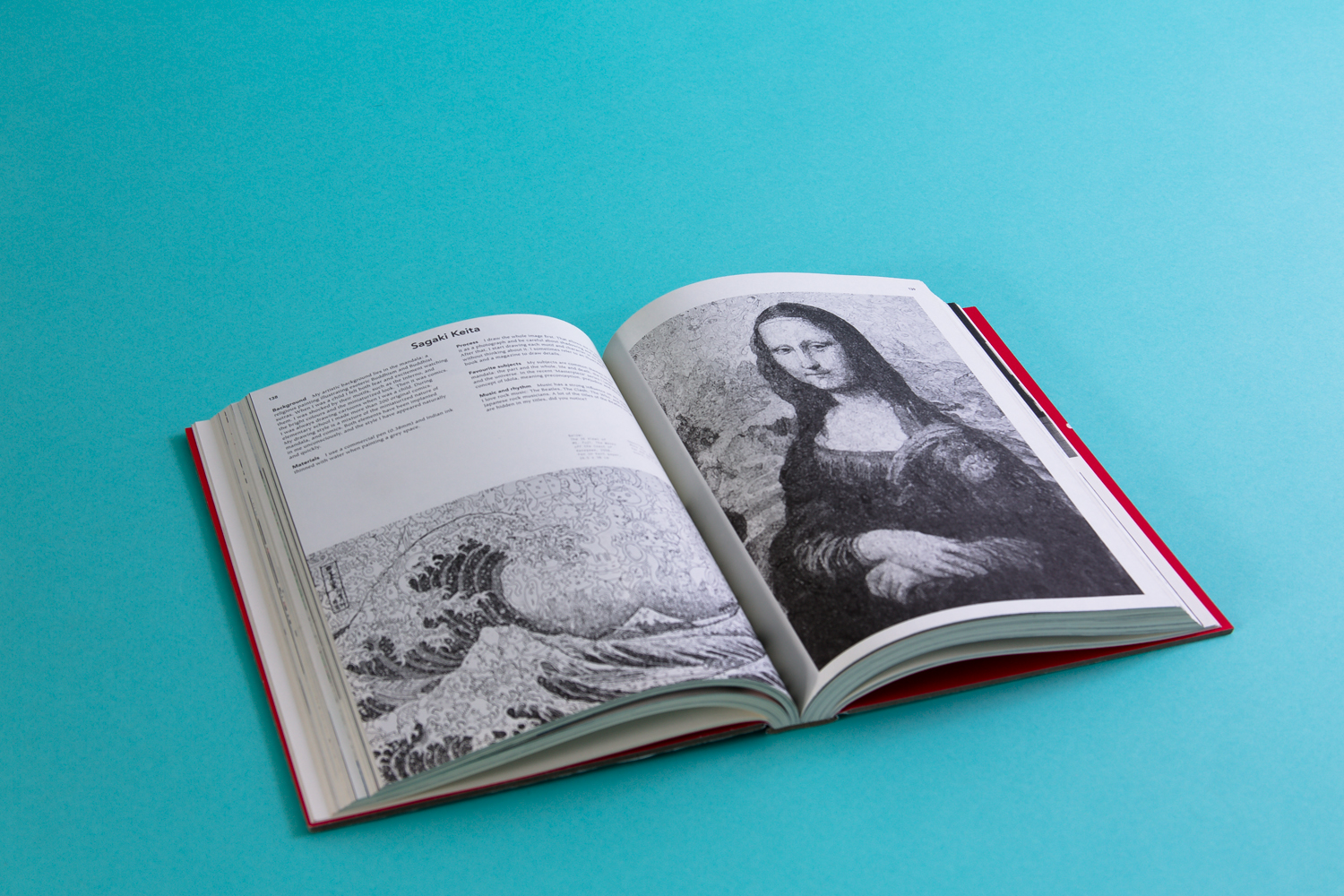

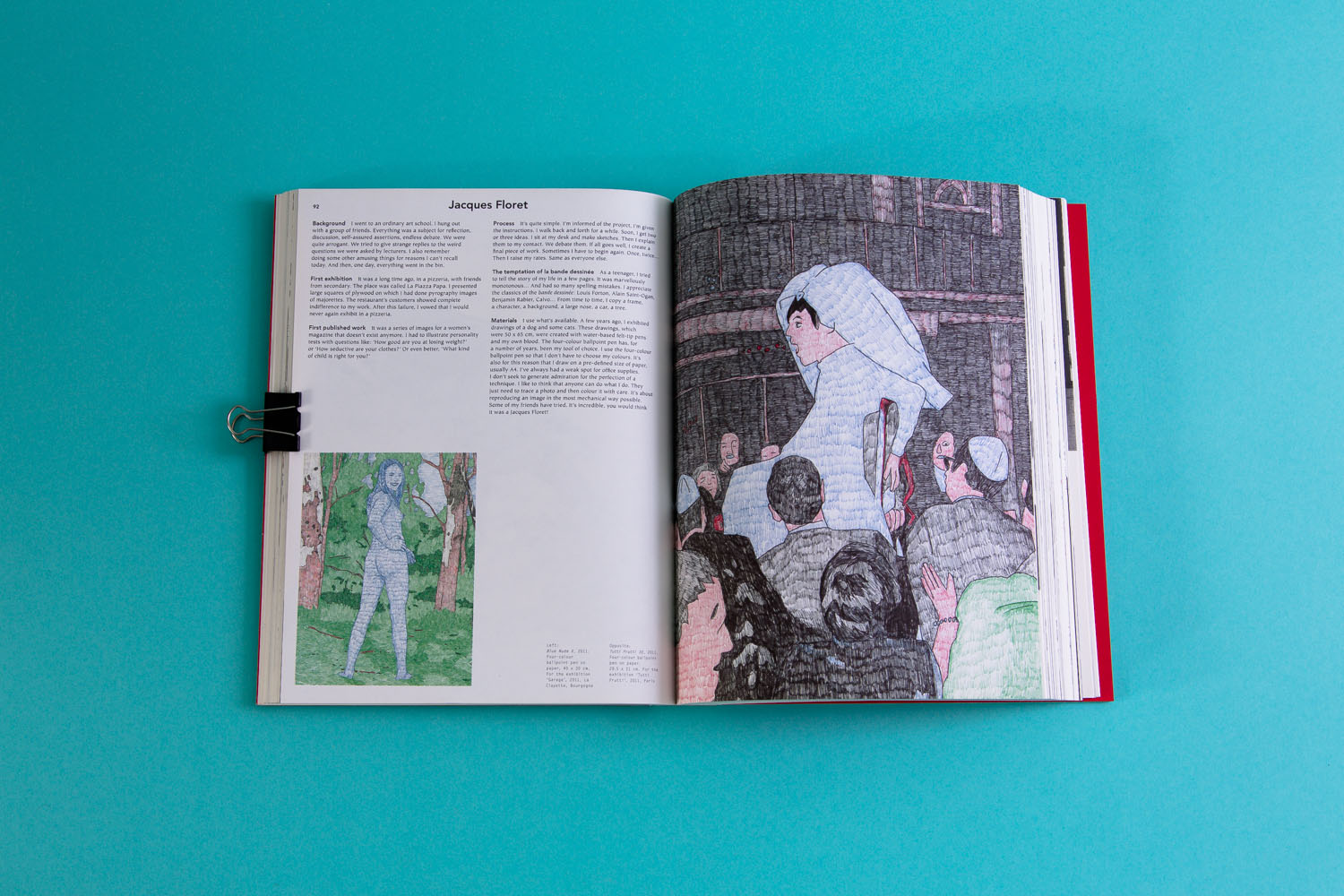

Much of the work here is characterised by a mixing of motifs and topical hierarchies that reads, somewhat ironically, as the thumbprint of the internet’s virulent content culture. Thus attitudes familiar to contemporary video and photographic artists are also much in evidence. Those works that approach some idea of objectivity quickly sidle off towards less stable territory: the soft focus cinematic stills of Erin Fostel and Marcel Gähler, the Tumblr-esque celerity of Jacques Floret (a kind of social media realism), the a-historical bricolage of Sagaki Keita or Carine Brancowitz’s self-consciously cropped and coloured portraits. Drawing has offered a riposte to both the arenas of fine art and technology by co-opting their attitudes and methods. With this, there is also a turn towards the positively surreal. Here it is again phrased less as an adventure into the psychological unknown, rather as the recording of a day-to-day existence bounded by a glut of visual media: our contingent surface reality. Hence Joe Biel’s darkly suburban fantasies, John Copeland’s brackish comedies and Emilio Valdes grotesque machines all manage to shock without surprising.

An important debate raised in light of these collected artists, especially those that place their emphasis either in making works of prodigious size or with intense density of information, is the notion of labour, or even more contentiously, skill, in relation to contemporary art practice. The indexical nature of drawing, and the familiarity of its methods to a general audience, leaves the story of a drawing’s construction elementally bare; drawing is, in effect, the most rational of all artistic endeavors, and it is easy to see how these works might speak to sectors of the public disenfranchised by the opacity of what they term, often derisively, modern art. Indeed, even for those steeped in the appropriate historical and theoretical idioms, it is easy to be overawed by the sheer human ingenuity and attritional application of much of what is displayed here.

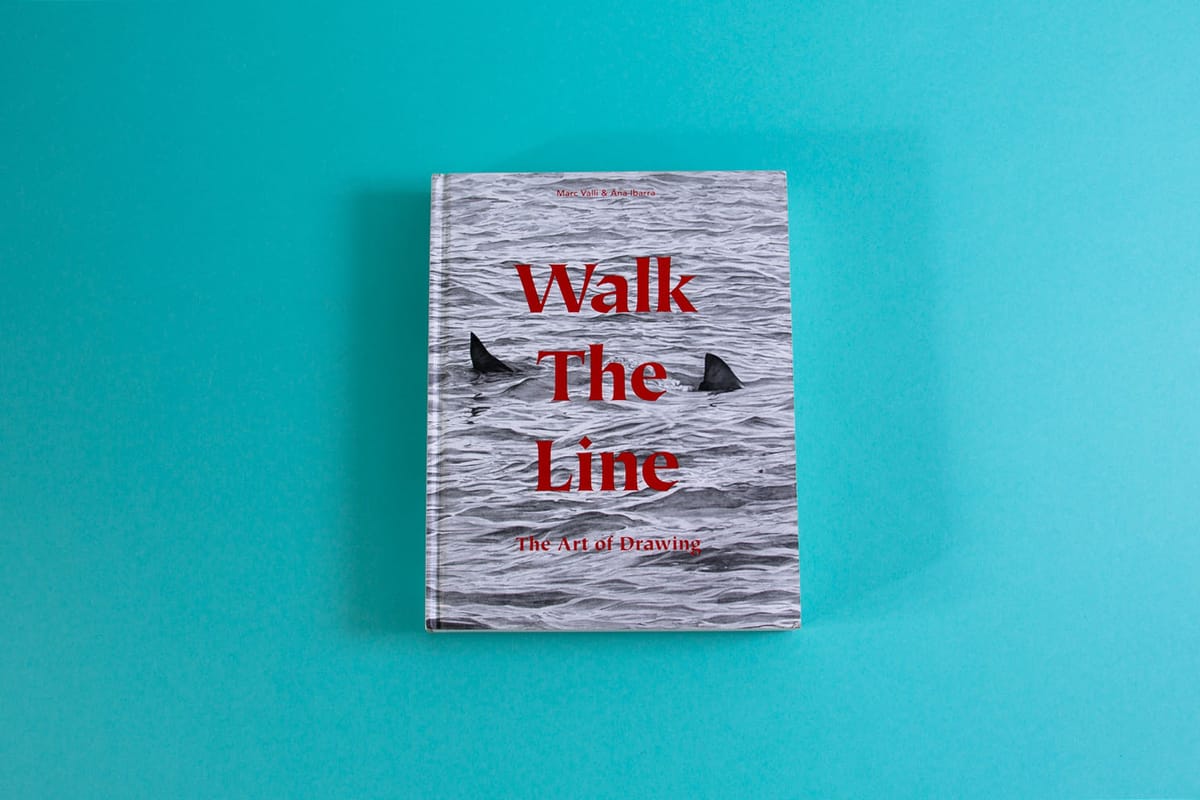

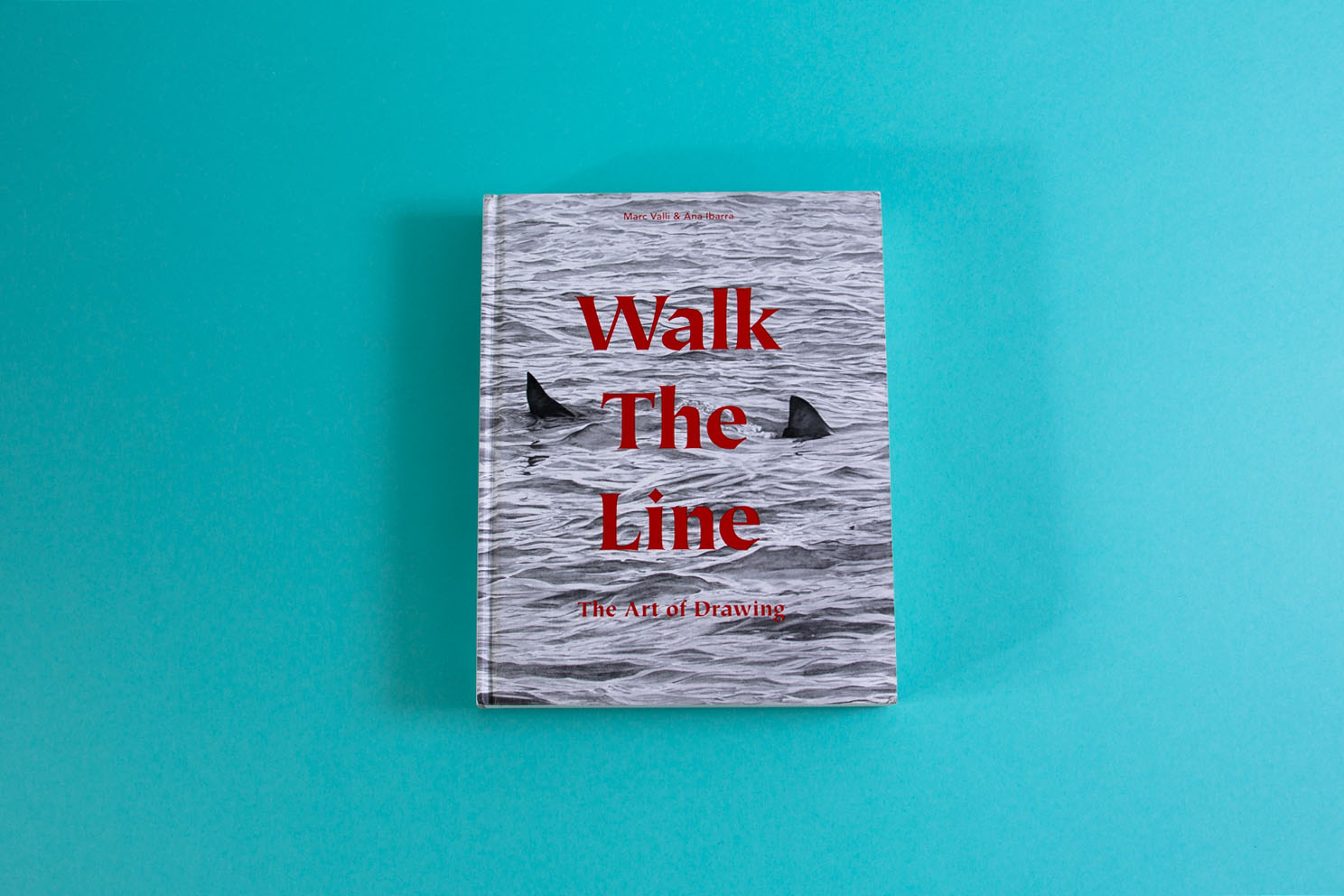

While the book acts as a valuable reference, what really elevates Walk the Line above the typical arts compendium is its design and production. Editors Marc Valli and Ana Ibarra are also responsible for the quarterly art magazine Elephant, currently art directed by London-based studio Julia, and they have adopted the same team for this book project. Walk the Line displays that combination of astute typography and bold colour choice that we’ve come to expect from the design trio. Their use of ITC Tiepolo, especially at the larger weight in the preface, provides a fantastic foil for the book’s subject matter — each of the type’s glyphs feel like it is constructed from a series of firmly applied marks from a calligraphic pen. It’s an ornate font that never feels merely decorative, in fact as it gets heavier it takes on shades of a blackletter, something like Rotunda, but retains a contemporary edge — as its designer Cynthia Hollandsworth remarked, it acts like a “sans serif with serifs”. From its time working on Elephant, Julia understands how to integrate a diverse range of visual material at scale, with none of the works feeling undeserved. Match this with a heavy, uncoated cream paper stock, repetition of a deep vampish red that acts as colour motif and the thick unsealed boards front and back that give the title its precise outline and you have a product that feels far more considered than most other offerings in this category. Walk the Line - The Art of Drawing, by Marc Valli and Ana Ibarra

Published by Laurence King, £24.95