A new exhibition at Liverpool’s Bluecoat Gallery explores the glitches present when capturing the world with digital technology and asks how the scan can redefine the concept of printmaking.

The verb ‘to scan’ is one of those rare semantic enigmas in the English language where a word means both one thing and simultaneously its opposite. Like cleave or sanction, this peculiar quirk entails that the act of scanning can involve just a quick, cursory glance or an in-depth viewing, recorded with great scrutiny. It’s an idea that piqued the interest of Jo Stockham, the RCA’s head of printmaking, when she was tasked with curating Liverpool gallery The Bluecoat’s new exhibition The Negligent Eye. The show explores how printmaking has moved on from a traditional craft dialogue to include digital technologies, three-dimensional forms and new ways of image-making.

Its no wonder that the concept has been at the forefront of Stockham’s mind during the four years she’s headed the school, considering her tenure has been heavily bound in with relocating the department from the 1960s Darwin Building to its new Haworth Tompkins-designed home in Battersea. By working out what equipment to retain and which new technologies to invest in, Stockham has pushed her students to asses what printmaking might mean in an age where access to technology has never been greater.

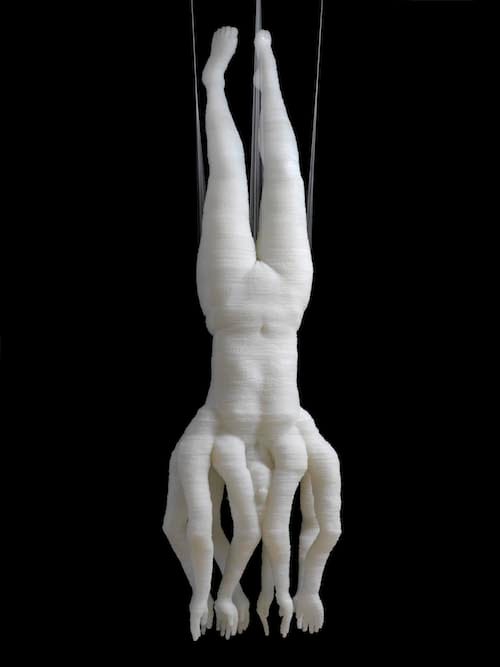

But the exhibition also aims to pose bigger questions about the scan. Artist Marilène Oliver has created monstrous distortions of the human body by hacking technologies used for medical scanning and cutting and pasting the data to form contoured plastic renders. “Here is an example of how that data becomes three-dimensional and is given body again,” says Stockham. As well as delving into the processes of CT and MRI scans, Oliver’s work also touches on an interest in the amount of data about our physical selves held on file, and how that data can be used, or misused, to construct a picture of who we are. Also interested in data kept in the public sphere, twin sisters Jane and Louise Wilson create self-portraits wearing camouflage make-up designed to baffle the face-recognition software used by law-enforcement and security agencies. Stockham says, “There’s a way in which this constant surveillance society is creating a countermovement in terms of people wondering whether cameras and ‘security’ are actually making people safer or rather intruding on their privacy.”

The interaction between technology and the body is also key to Beatrice Haines’ electron microscope scans of her grandmother’s gallstones, which when shifted in scale and backed with light boxes become beautiful planet-like orbs. Similarly to Oliver’s warped human replicas, London Fieldwork’s playful project taps into medical machinery, this time electroencephalogram recordings used to depict electrical activity in the brain, to give physical shape to the body-mined data. Inviting artist Gustav Metzger to ‘think about nothing’ while hooked up to their machine, the data was transferred to a manufacturing robot which then carved his non-thoughts into Portland Stone. “The process was enabled by certain advances in technology but still relates back to the fundament principals of printmaking in terms of using positive and negative space,” adds Stockham.

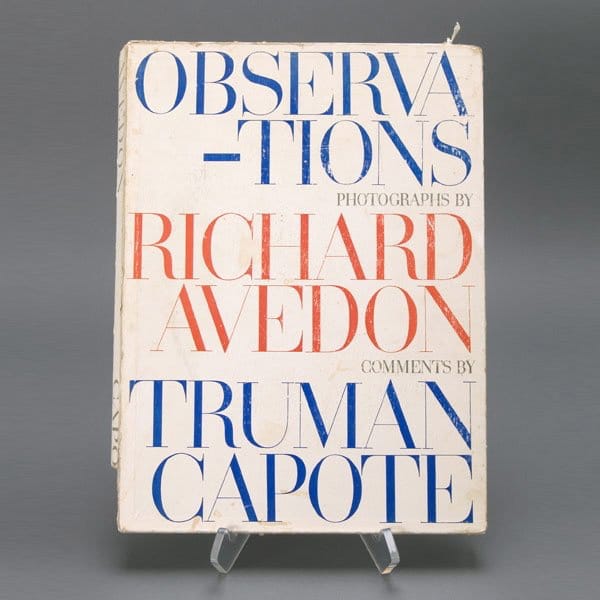

Indeed, throughout the exhibition there is frequent reference to the historical precedents of featured work, as well as early printmaking pioneers. Haines’ gallstones nod to the practice of Robert Hooke, the first man to ever look through a microscope, who also made influential prints of flies’ eyes and the tips of needles. The show also features an 18th century engraving by Thomas Bewick, who traced the linear structure of his thumbprint and used it as a form of signature, long before thumb-scans and identity cards were ever part of the political agenda.

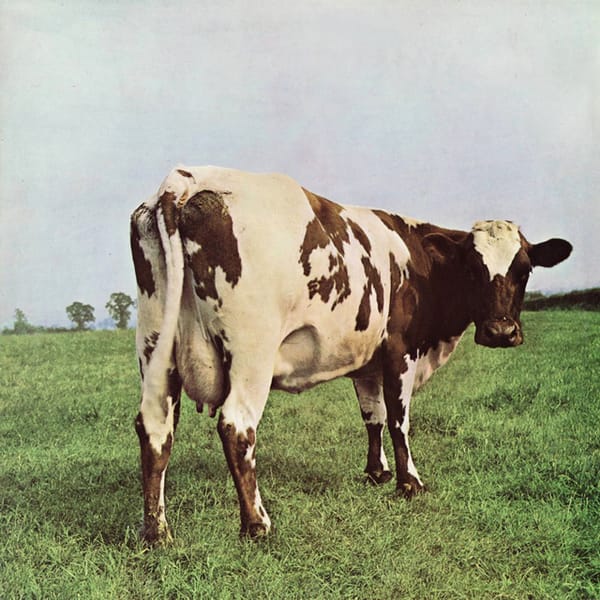

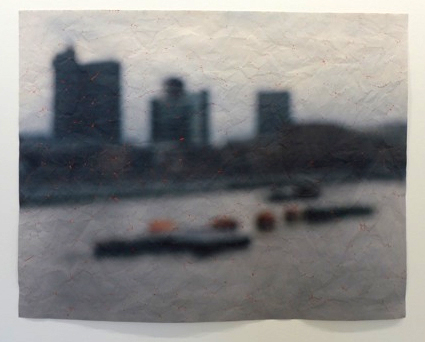

Unsurprisingly, authenticity and the problems of capturing the physical environment is something many of the artists are keen to explore. Nicky Coutts renders estates building into baroque environments through repeating small segments, and Stockham’s own print Never Home is deliberately blurred and damaged before its subject is semi-reclaimed by hand-inking the broken surface. Indeed breakages and blips are far more prevalent than faithful representations. Elizabeth Gossling captures odd interference scavenged from TV screens using a hand-held scanner, and Susan Collins’ London 2014 presents the capital’s skyline in constant flux, scanned live and sent pixel by pixel to be written and rewritten on to the Bluecoat’s walls over the course of a day. “A lot of digital technologies, or fantasies about technology, centre around the idea that it can be used to capture the world,” says Stockham. “I’m interested in critiquing that notion and showing some of the structures with which we try.”

The Negligent Eye

The Bluecoat Gallery, Liverpool

Saturday, 8 March – Sunday, 15 June 2014