With a drive to rethink traditional ways of working, London-based studio Europa boasts an accomplished body of work that is as notable for its clarity of form as for its collaborative focus.

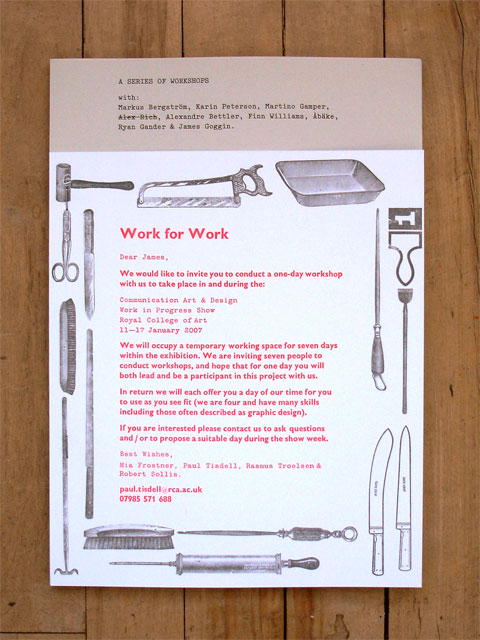

“The principle of Work for Work is that person A works for person B for an agreed amount of time, and in doing so they agree that person B will repay person A with their time. This exchange of labour allows each party to experience how the other works first hand, giving both a strong understanding of the other’s practice. We are keen to build relationships where we can continue to explore this method for working and exchanging with people, and would encourage others to do the same.”

So begins the introduction to Work for Work, a project initiated in 2007 by newly-formed design studio Europa. Its premise was simple – founding members Mia Frostner, Robert Sollis, Paul Tisdell and Rasmus Troelsen approached people whose work they admired, with a proposition: give us a day of your time, and we’ll give you a day of ours in return.

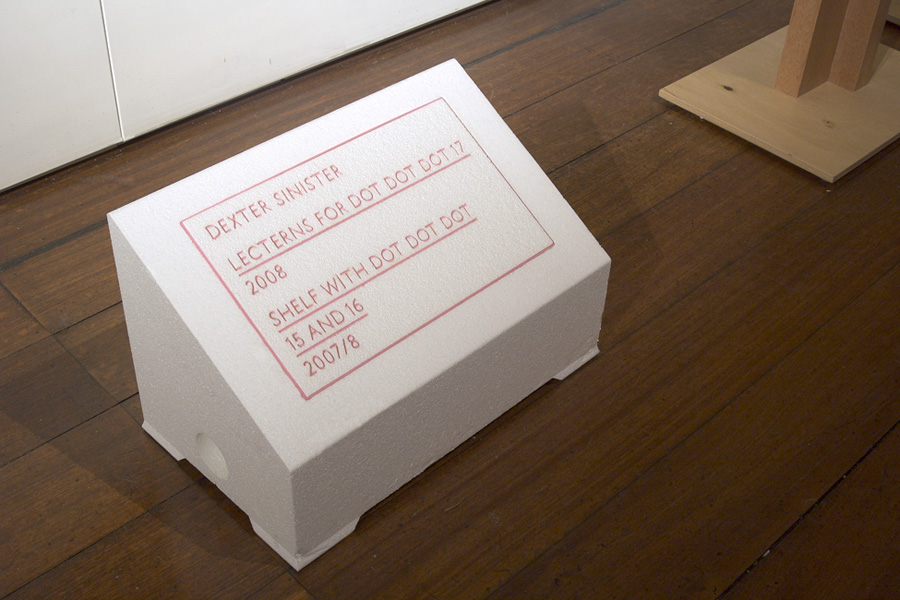

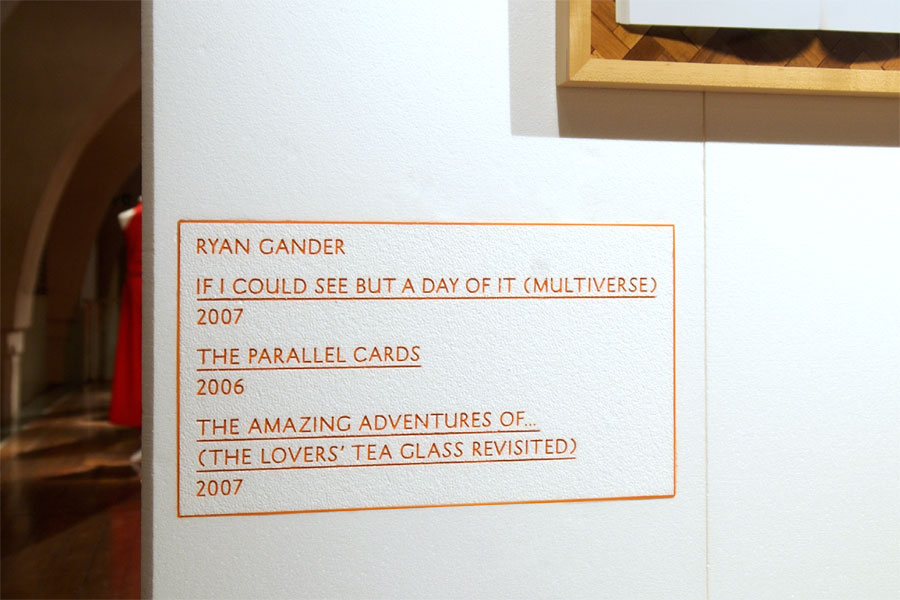

If [our project] works, it will have a positive effect – however small or large – on the city and how people live, and there’s a political side to that which we feel quite strongly about. Their initial aim was to find hosts for a series of workshops, to be held for their Work in Progress exhibition at the Royal College of Art where the four were studying. Soon, though, the project took on a life of its own, with other participants trading time and skills. With contributions from an array of artists, architects, fellow designers and writers, the collective output of Work for Work is intriguing, including everything from choral performances to furniture design. It was an ambitious undertaking, and an enviable achievement for the group – few others can list collaborative projects with the likes of David Hockney, Ryan Gander or Bill Drummond on their CVs before they’ve even collected their MA certificates.

Brilliant networking ploy it might have been, but Europa had other, more complex motives for the project. “In part, it was a way for us to find structure and purpose within the loose, cross-disciplinary nature of our course,” they explain. “But we were also thinking about the hierarchy within any working relationship. The project was a framework that encouraged a flattening of that hierarchy – one day we would be the client, and the next, that relationship would be reversed.”

The reciprocal spirit of Work for Work seems to have set the tone for Europa’s practice over the seven years since. Working with an impressive list of clients from the worlds of art, architecture and urbanism, they’ve built a sensitive, accomplished body of work that is as notable for its clarity of form as for its collaborative focus.

Europa was initially borne out of a mutual desire to continue with the kinds of project its members had begun at the Royal College. “We didn’t have a plan,” Sollis recalls, “other than to carry on with the work we were doing, and eventually make enough money to support ourselves doing it.” In that way, many of the studio’s first projects sprung from the relationships its members founded during their studies. Ryan Gander was one such collaborator, having already participated in Work for Work – for his workshop, he challenged attendees to write each others’ obituaries, and Europa designed a pack of double-faced playing cards for him in return.

Europa was initially borne out of a mutual desire to continue with the kinds of project its members had begun at the Royal College. “We didn’t have a plan,” Sollis recalls, “other than to carry on with the work we were doing, and eventually make enough money to support ourselves doing it.” In that way, many of the studio’s first projects sprung from the relationships its members founded during their studies. Ryan Gander was one such collaborator, having already participated in Work for Work – for his workshop, he challenged attendees to write each others’ obituaries, and Europa designed a pack of double-faced playing cards for him in return.

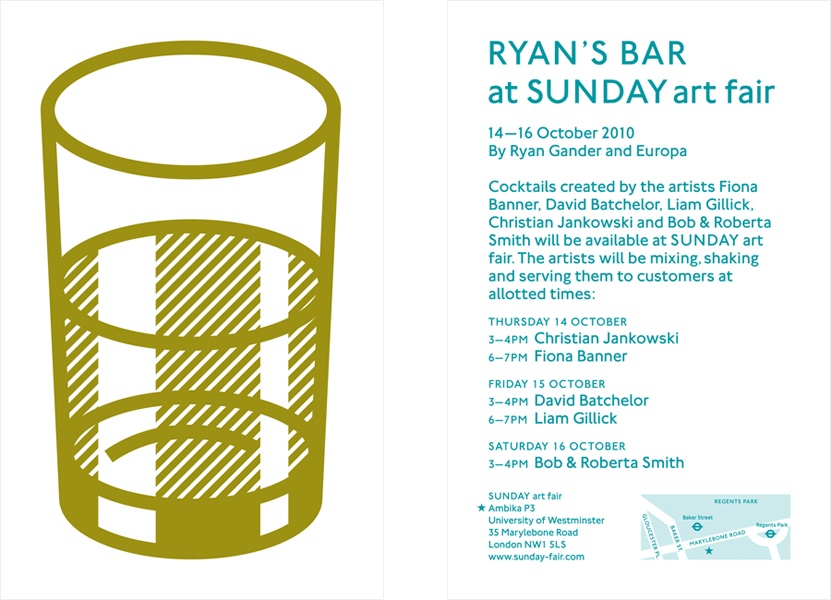

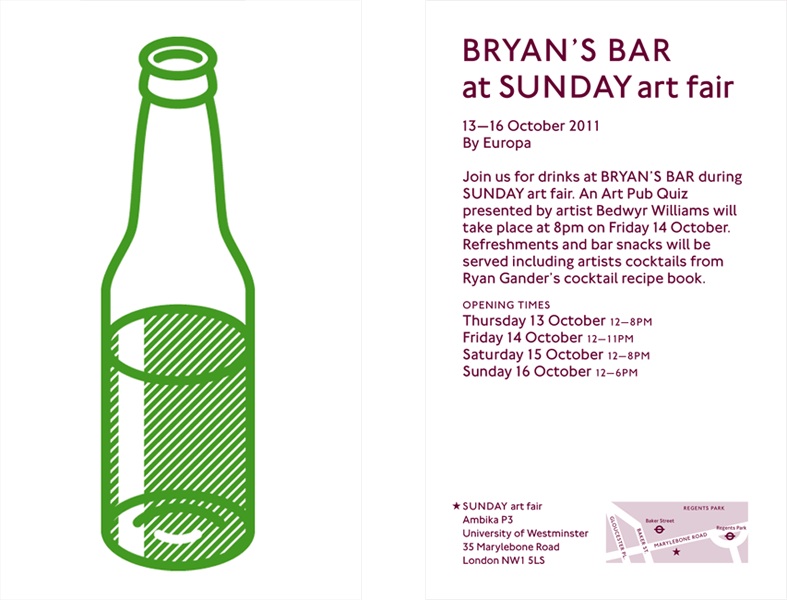

Gander’s confidence in Europa is evident throughout their work together – amongst which were the design of his publication, Loose Associations and Other Lectures, for Onestar Press, and the identity of Ryan’s Bar, a pop-up venture opened by the artist for the Sunday Art Fair. “Ryan is very sensitive to design, but he’s also trusting if he knows you’re making good decisions,” they say of this ongoing relationship. “He lets you get on with it and develop an idea. Some artists are more comfortable working with designers than others – some always want to feel more like they’re directing you than working with you.”

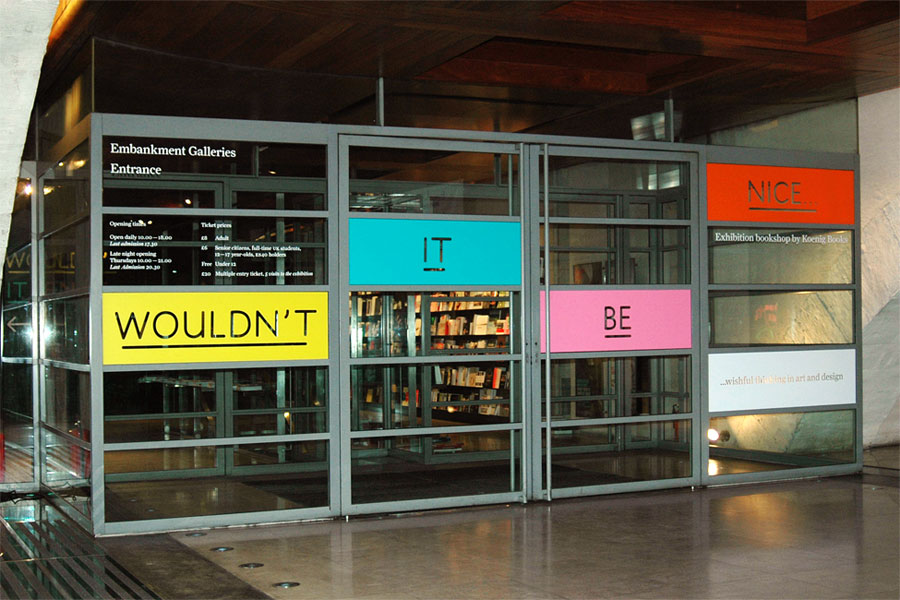

It was Gander who introduced them to their current studio space – a bright unit in the former car park of a block behind London’s Kingsland Road. From there, they’ve continued to work on artist-led projects, with their playful yet measured approach clearly evident on publications for clients including Sternberg Press and the South London Gallery, and exhibition design for the likes of Somerset House and Sweden’s Gustavsbergs Konsthall.

In recent years, however, Europa’s work has taken a turn towards architecture, and in particular, to place-based projects which intend to serve the local communities of London and beyond. Seen in that context, their studio’s situation – within a residential estate, and in the midst of the everyday comings-and-goings of the East End – seems appropriate, coincidence though it might be.

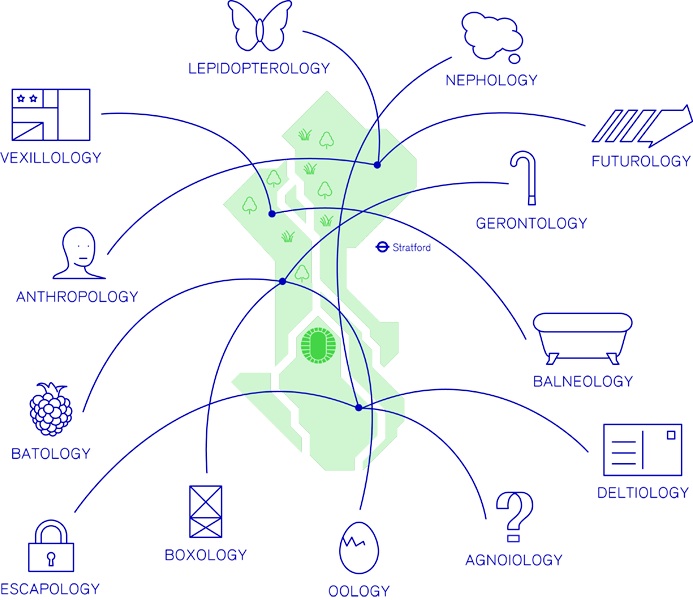

The first forays into that world came again through collaboration with their Work for Work compatriots. In particular, a workshop held with Finn Williams and David Knight, at the Architecture Association’s summer school in 2009, seems to have heralded the start of this particular strand of their practice. Titled Sub-Plan, it was based around recent changes to planning law, and challenged students to produce “something tangible and useful” in their time there. The resultant publication Europa designed with the students showed how, with a little nous, people planning their own building projects could make new regulations work in their favour.

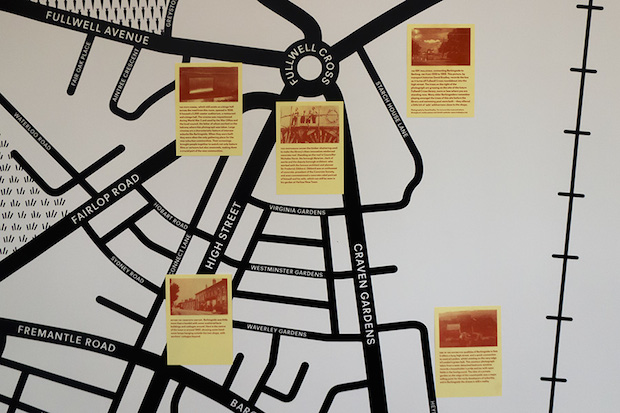

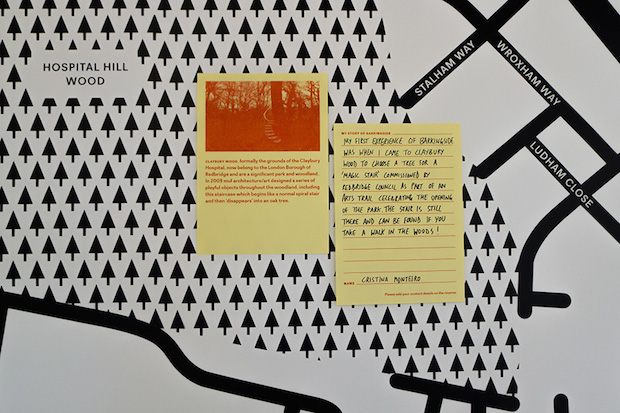

Teaching gives us an output for avenues of research which we wouldn’t have within commissioned projects. Other projects in this vein soon followed. Some, such as the Front Room in Barkingside, looked to shed light on the borough’s underexplored heritage – using design as a medium to tell stories, and to engage local residents with the history of their locale. Others, like their ongoing wayfinding work with We Made That for the Blackhorse Lane industrial estate, build links between the residential and industrial occupants of the area. In this case, they commissioned photographer Thomas Adank to take a series of still-lifes that celebrate the items manufactured on the estate. Currently on display on billboards around Blackhorse Lane itself, they form a bright intervention into their urban surroundings.

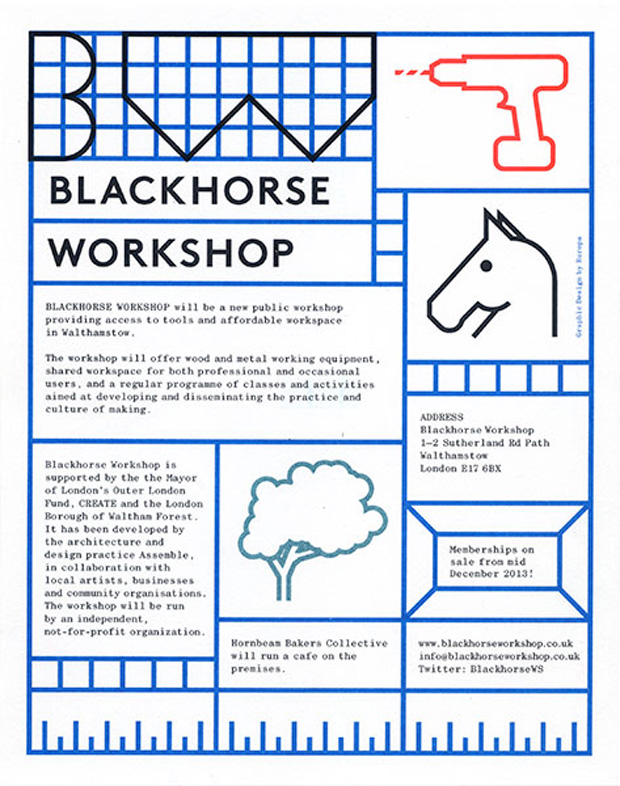

Another recent project based in that same area is the identity and signage for Blackhorse Workshop, a new workspace for wood and metalworking which Europa describe as “in the spirit of a public library – a social space as well as a resource for all sorts of artists, designers and DIY-ers”. Early discussions with their collaborators, the architects Assemble, formed the basis of their graphic approach, with the resultant design’s strong grid and bold use of line taking cues from the identity of the Wiener Werkstätte - a workshop founded on similar principles in the early 21st century.

Europa’s work on these urban, community-focused projects is a welcome reminder that design for a general public audience need not be dry or pedestrian – and the idea that their work might contribute to the common good is clearly important to them. Speaking about the studio’s ongoing work on Building Design, a web portal conceived by David Knight that builds on the ideas behind Sub-Plan, Sollis explains: “If it works, it will have a positive effect – however small or large – on the city and how people live, and there’s a political side to that which we feel quite strongly about. Equally, Blackhorse Workshop might re-engage people with making and with materials. At a time when funding for public libraries is being cut, it’s very exciting to see public money being put into a place where people can make and socialise at the same time. That feels really positive.”

Alongside all this, Europa have maintained a fluid approach to their studio structure, with founding members pursuing their own professional interests, either alongside or apart from their studio practice. Troelsen left in 2009 to move to Copenhagen, and at the time of writing, Tisdell is in Australia, though still a ‘sleeping partner’. Meanwhile, Sollis and Frostner remain at the helm in London, joined by freelance designers Lorenz Klingebiel and Gareth Lindsay – “both of them will be running their own studios before too long,” Sollis notes, “but we’re lucky enough to get the benefit of their assistance in the meantime.” They devote a considerable amount of time to teaching, and are currently leading the second year of Camberwell College of Art’s BA Graphic Design course, as well as undertaking an impressive range of talks, workshops, forums and symposia.

The key to balancing this with their commercial work, it seems, is to treat teaching as another ongoing studio project, rather than something on the side. “It didn’t feel like a conscious decision to teach alongside having a studio,” says Sollis, who was already teaching at Camberwell when the four met at the RCA. “It was just something that was happening.” An early stint tutoring on the graphics programme at Winchester University set Frostner and Tisdell on the same path, and their combined activities in design education have gone on inform Europa’s practice as it developed. “Teaching gives us an output for avenues of research which we wouldn’t have within commissioned projects,” they explain. “There is often a dialogue between ideas that we are having for projects in the studio and ideas that we are having for briefs for students.”

The notion of balance – whether between teaching and commercial work, the client/designer relationship, or individual and collective professional goals – is clearly at the heart of what Europa do. It’s also the first thing they touch on when asked about their ambitions for the future:

“Balance is always the key. There’s no particular area or field we’re really focused on moving into, it’s more about having enough time to research and study, enough time to build on the relationships that we already have, and to develop new ones that might take us in an exciting direction. The most important thing is that we look forward to going to studio in the morning – and we do.”