Photographer Dan Tobin Smith’s colourful installation for LDF 2014 combined fact and science-fiction to create an attractive yet ugly picture of contemporary life.

Most of the products with which we surround ourselves have been classfied by appearance: white goods are large domestic appliances such as washing machines, fridge/freezers and ovens; brown goods (a term based on the bakelite casings they once used) are smaller devices — countertop machines such as radios, your teasmaid or your Nespresso; shiny goods are (being shiny) the most exciting — consumer electronics such as camcorders, mobile phones or robot vacuum cleaners (in fact this last could make a claim for sitting in several categories, or even provoking a new classification (infrared goods?), showing that there is an amount of bleed-through between camps.

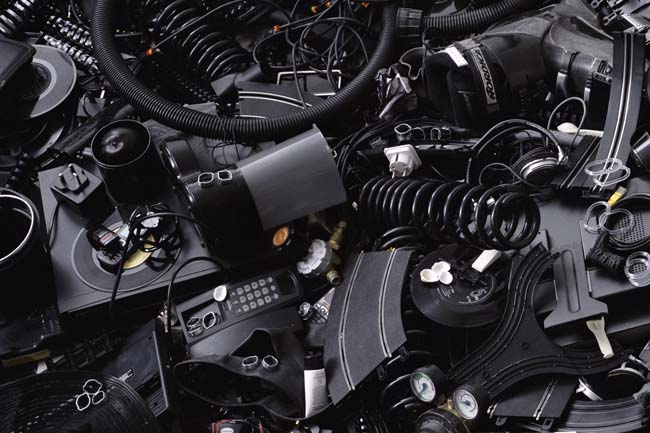

A picture of the world painted in these colours would be unremittingly drab, and today they are largely inaccurate descriptors – the terms were coined in an earlier era, one in which sparkling white was considered the necessary associate of proper hygiene, the technological future was phrased in soporific silver-grey and polyoxybenzylmethylenglycolanhydride (Bakelite) could only run a spectrum of umber to auburn. To see quite how different things are now you only needed to pay a visit to photographer Dan Tobin Smith’s East London studio last week. On entry to the open-plan, double-height space, you stepped into a rectilinear clearing amongst a sprawl of chromatically arranged junk, things piled upon things, stuff stacked up against effects and bits jostling bobs in highly ordered disarray. Every type of item was accounted for, from computers to cookware. These shaded from puce to purple to indigo and off into the marines, waxy black along one back wall and with a corona of white where the tide approaches the irregular path provided for onlookers.

Tobin Smith chose to use a very specific term for this collected material. The exhibition was titled The First Law of Kipple. Apparently “kipple” is something that the photographer has been obsessed with since his early teens, or more accurately the idea of kipple; we’re all obsessed with it in its actual form, that being the point that provoked the concept into being in the first place. The word originates from Philip K. Dick’s sci-fi novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?. It is explained there as “useless objects, like junk mail or match folders after you use the last match or gum wrappers or yesterday's homeopape.” Needless to say, kipple has been readily adopted to describe the excesses of consumption and production that have characterised modern economies from the middle of the last century, much as Dick likely intended and hoped.

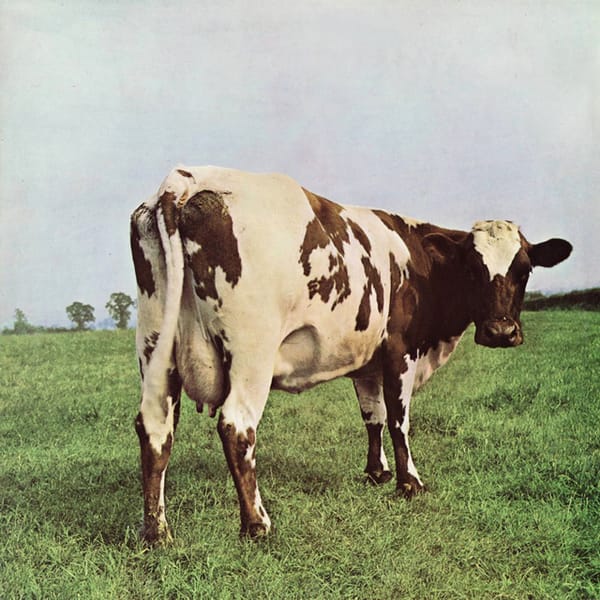

The concept presented here originates from an earlier project that Tobin Smith completed for the cover of Mark Miodownik's book Stuff Matters, an investigation into the genesis and use of man-made materials. There, (much less) stuff fluxed across the colour wheel in an aggregate photograph to advertise our reliance on said mercurial inventions. Tobin Smith has used photography here, too, to create a series of scaleless trash-scapes that shuttle between half recognised forms and vibrant abstraction, titillating in the same way as a confectioners window, e-colours advertising tooth rot. Though this installation doesn’t set out a specific agenda, any preachy statements on environmentalism, say, it is far more than just a pleasing spectacle trading on cult-lit terminology and the more provocative for avoiding didacticism altogether.

Tobin Smith is interested in the psychological effects of clutter and the means of contending without [or ‘with our’?] over-stocked environment in much the same way as Dick’s characters. The important thing to note about kipple, they tell us, is that it multiplies when no one is looking. It has (tongue in cheek, we’re not sure) a life of its own – be that a satire on the ‘invisible hand of the market’, which doesn’t seem to provide adequately and correctly as much as to force-feed, or a more projective hint towards our now immediate future of fully-networked, semi-autonomous, potentially self-replicating nicknacks (and robot vacuum cleaners). In Dick’s novel, “absolute kipple-ization” is the universe’s end-game, a self-contained system returning to entropy.

As J.R. Isadore, the sidewalk philosopher of kipple states: “No one can win against kipple… except temporarily and maybe in one spot, like in my apartment, I’ve sort of created a stasis between the pressure of kipple and nonkipple, for the time being.” Tobin Smith has effected a similar stand within his studio, holding the detritus at bay by elevating it through an ordering process that shifts, for a moment, the mundane to the auratic, fending off entropy by returning some cerebral energy to an often unthinking system. We are well beyond the era of Henry Ford’s “Any customer can have a car painted any colour that he wants, so long as it is black”, and the range of hues represented here shows the full extent to which pseudo-individualisation is used to personalise the homogenous in pursuit of sales. But although the profusion of colour is the most striking element of this display, it is also the least important, an arbitrary criteria that allows the much more important process of arrangement to occur.

Tobin Smith is in a long line of post-millennials working through their anxiety about the things they procure and produce. Michael Landy set an early example with his Break Down project, in which he made an inventory of everything he owned, a list that took three years to complete and was 7,227 items long. He then employed a large machine, installed in a vacant apartment store on Oxford Street, to grind it all down to a fungible particulate, slapstick existential matter. Fellow photographer Huang Qingjun’s Family Stuff project, in which he spent a decade photographing households across China standing in front of their homes and surrounded by their worldly possessions, on one level suggesting a kind of insidious hybrid between portraiture and still life, one in which the human presence was clearly secondary to the act of portrayal. A stage beyond, Jeremy Hutchinson’s Erratum series of objects are actively misanthropic; the artist asked manufacturers to insert errors into their products (a holeless cheese grater, a toothless saw), offering a counter logic of mass production in which goods mutate away from functionality in order to remove themselves from a particular cycle of circulation. Each example was then sold as a luxury item.

As Hutchinson remarked “The endgame of luxury is when things slide into obsolescence: true luxury has no function… It is not something to be used or understood. It is a feeling: beyond sense, beyond logic, beyond utility. It is an ethic of perfect dysfunctionality.” That “ethic” feeds into a much wider narrative, that the largest part of our day-to-day consumption is unnecessary, the Frankfurtian assessment of mass deception, capitalism as an engine that runs on the production of false need and psychological dependancy; despite appearances, all the objects in The First Law of Kipple are luxury items at a point where obsolescence and disposal of any kind is a luxury that we (our planet) can ill afford. The kipplization of the universe has already begun: just look to the great Pacific garbage vortex, a gyre of chemical sludge and plastic pieces of inestimable mass at the centre of our largest ocean. Out of sight, out of mind; contrastingly, Tobin Smith’s vortex of colour will very visibly circle on – though its London incarnation has been swept away, it will be deposited in new locations and galleries around the world, a beautifully sugared pill.

dantobinsmith.com