There’s only one month left to see Barber & Osgerby’s In the Making at the Design Museum, a show that proves that it is not always better to finish what you’ve started.

Design, at least with a capital D, can be accused of having an unswerving interest in the final destination. The figure of the professionalised designer is the ultimate post-Enlightenment poster boy; that strength of belief in instrumental rationality — finding the most efficient path to resolve a given problem — leaves little room for happy accidents or chance operations. Recent trends, specifically in process-led design, have turned that paradigm on its head with their emphasis on the indeterminate; but what value, if any, do such perspectives hold for practitioners situated within that lengthy tradition of route one thinking? The Design Museum’s latest exhibition, In the Making, sees one established British studio answering that very question.

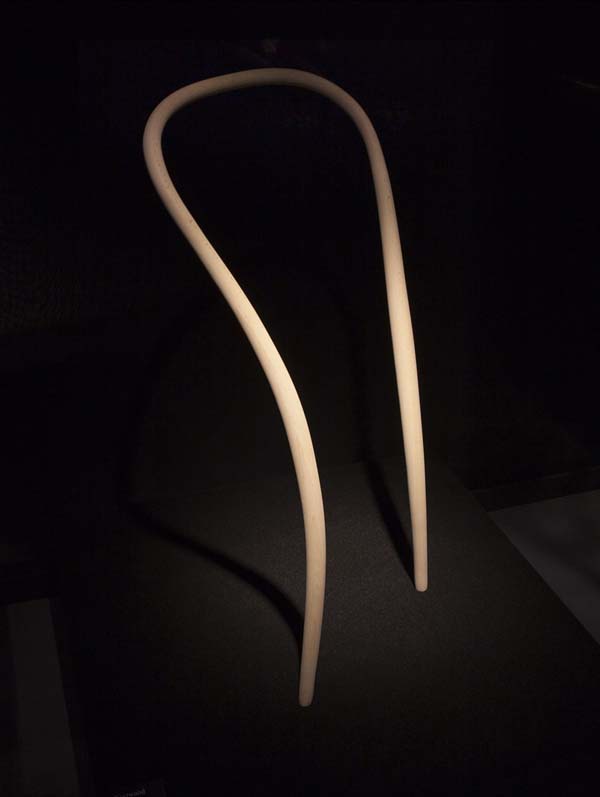

The show takes up only a fifth of the museum’s top floor, which has been blacked out and pedestals carrying twenty-four objects installed. Each of these have been selected by design duo Barber & Osgerby — they of Olympic Torch fame (included here) and various other refined products for luxury brands. The selection criteria extended not only to which items to include but also at what moment in their respective production cycles they would be arrested and transported to the exhibition space. A Nike trainer and a cricket bat at ten percent completion look more like a wrestler’s mask and building component, respectively; at fifty percent a sheet of tennis ball blanks and a Thonet chair look like a Biba sarong and an ancient instrument; at sixty, a set of Derwent colouring pencil like a slice of decking; at seventy, a glass marble like an erotic ornament. In the accompanying literature, the pair state that they “have always been fascinated by the making process and it is an integral part of [their] work.” It might seem contradictory to associate the bastardised objects displayed here with a practice whose works are so decidedly finished, (witness Barber & Osgerby’s 2011 exhibition Ascent at Haunch of Venison for an extreme example) but it follows that such a level of completion can only arises from an intimate knowledge of the steps taken to achieve it.

This array also speaks to the curators’ own material tastes. A fist of unground Swarovski crystal and a cone of bright silica waiting to be sliced into wafers each recall the studio’s sense of opulent simplicity. In much the same way as the pair approach their own projects, these items wait to be paired back until they achieve a form of mannered perfection. That is to say that In the Making is a cipher for the Barber & Osgerby ethos, rather than a dedication to the studio itself. Admittedly a few of the items, a two pound coin released for the 150th anniversary of the London Underground and a Tip Ton chair for Vitra, are of their own conception, but they are here only on the merit of their fascinating construction narratives. Other objects indirectly reference the studio aesthetic: the trainer and the tennis ball wastage, for instance, are indicative of the sharply graphic element that it brings to its three-dimensional forms, typically composed of definite and memorable silhouettes.

Barber & Osgerby note the unexpected “beauty” displayed by these transitory objects and, given their tendency towards the recherché, perhaps that is to be expected. Hansgrohe’s Axor Tap brass casting blank does have a surprising sculptural intensity when eighty percent from resolution. Perhaps more importantly, In the Making addresses the fact that, in an age when an increasing majority live under urban conditions, surrounded by predetermined forms with little room for error or intervention, most remain entirely abstracted from the means by which their environments are delivered to them. Hence why In the Making largely ignores the esoterica of the design world in favour of the quotidian and the accessible: turning the familiar strange invites different modes of interpretation.

That Thonet chair-back is a serendipitous inclusion. Le Corbusier used the chair as an example of his notion of the “objet-type”, the standardised forms of the (then new) mass manufacturing culture. This formulation arose from the designer’s attempts to move painting on from Cubism, in which objects would appear as fractured, towards his brand of Purism, in which such objet-types would be returned to a unified platonic integrity. The “banal[ity]” that Corbusier claimed for such objects was part of his desire for a demotic design language that would later arise in his built forms and products. As the late British design theorist Reyner Banham put it, Corbu wanted to identify “absolute” objects “beyond the reach of accidents of personality, perspective or time” — what we have perhaps learnt is that these objects have become too far removed and, as such, the authenticity of our relationship with them, and the consequences of our decisions regarding their employment, have become attenuated. In the Making shows the objet-type to be another modernist myth in which it is dangerous to over invest.

Design is too often measured against the ability of unique objects to fulfill narrow parameters of usefulness. Half-made or half-corrupted products might be labeled as useless, but during a period in human history when what we extract from the planet for manufacturing and what we return to it as waste is of ever greater consequence, it is important that we all learn to look at these states not as empty but, conversely, as burdened with potential. It is in the moments immediately before and after the life of any product that design has its real efficacy.

In the Making,

Design Museum, London

Wednesday, 22 January — Sunday, 4 May 2014