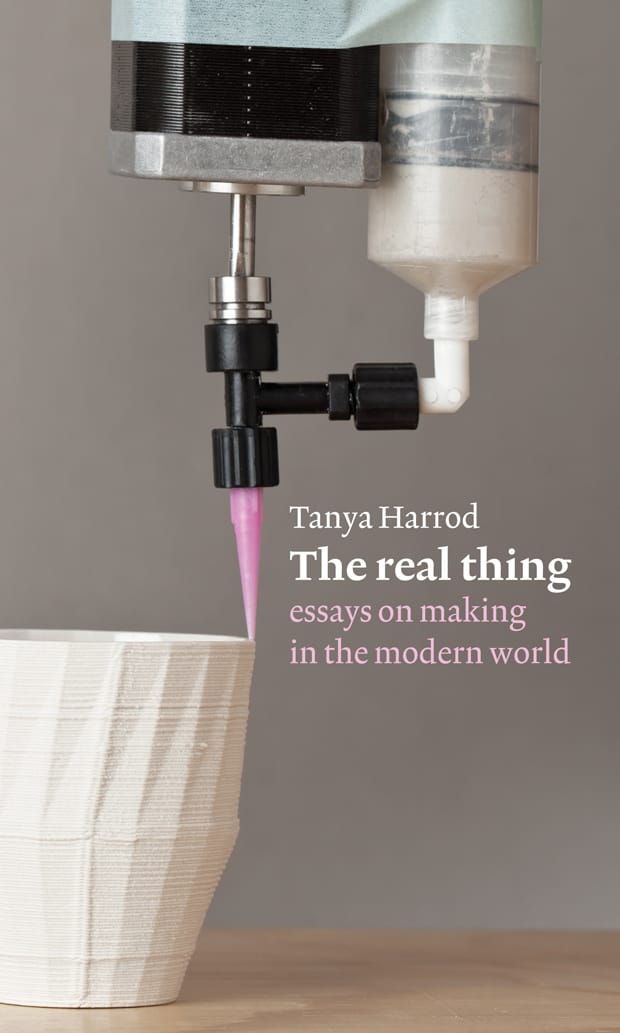

Hyphen Press’s latest offering, The Real Thing by Tanya Harrod, is a collection of essays on making that together provide a timely and comprehensive reflection on its personalities, histories and debates.

'This is the centenary of his death but it is patently not Morris's moment', writes Tanya Harrod of the 1996 William Morris exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum. The reviewers of that exhibition apparently contriving to blame the polymath Morris for everything from Laura Ashley wallpaper to the atrocities of the Khmer Rouge in a polyphony of lazy and alarming accusations. Today, Morris’s legacy is receiving a reprieve; the relevance of the ideals and politics behind his radical craft practice to our contemporary society and to the art and design of the twentieth century – as focused on by two recent shows at the National Picture Gallery and Modern Art Oxford – are both evident and acknowledged. Morris’s personal revival clearly plays into a broader resurgence in making as an idea, with a deluge of recent exhibitions, independent magazines and websites all devoted to interlocking ideas of authenticity, making and nature. In this light, The Real Thing: essays on making in the modern world, Harrod’s collected writings spanning the last thirty-five years, have been released at an apposite moment by Robin Kinross’s Hyphen Press. Harrod’s inquisitiveness about the processes, people and politics behind craft and making couldn’t feel more contemporary; the fact that so many of the essays aren't exactly that highlights Harrod as a writer of rare certainty, who has engaged deeply with an area often over-looked by art and design critics alike across the past three decades.

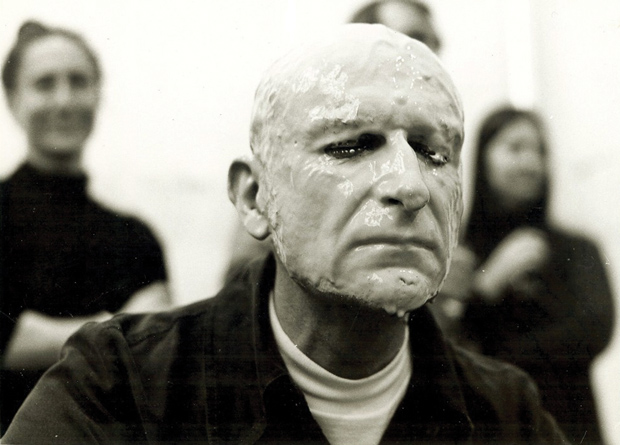

The writings in The Real Thing arc across time, place and artistic categorisations with an approach that always keeps the bigger picture in view: a consistent feature which contributes to the neatness of these writings as a collection. This erudite approach from Harrod is coupled with a snappy, eloquent and precise essayistic style. One short review of an exhibition at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge unabashedly asks ‘... why make art at all in such a full world?’ – getting straight to the crux of the matter – while an un-romantic but fair reading of Alexandra Harris’s Romantic Modern’s summarises the book eloquently in a single phrase: ‘In England, the insular and the avant-garde were intertwined’. An article on where to see folk art, or Mingei, in Japan sits comfortably alongside a review of Jeremy Deller and Allen Kane’s Folk Archive exhibition, which – in typical Harrod style – spends the first four paragraphs dealing with the larger question of what folk art is, drawing in the thoughts of Enid Marx among others. Such is the holistic approach employed by Harrod that several of these short articles on overlapping subject matter can act as highly accessible and surprisingly thorough introductory readers to a subject. Alongside Harrod’s reviews sit biographical vignettes from the history of art, design and making. One that particularly stands out is the image of radical poet, writer and cabinetmaker Norman Potter, imprisoned in 1948 for confronting a military tribunal on the ethics of war, and in solitary confinement for non-cooperation, scratching prophetic lines of W.H. Auden into the wall with an old pin: ‘look shining at / new styles of architecture, a change of heart’.

In The Real Thing Harrod maintains a remarkably objective view of craft practice, and never rejects technological developments and interrelations without fair assessment. ‘Ancient crafts like barrel-making and dry-stone walling ... are finding new practitioners through countless micro-communities that operate as online networks’, points out Harrod in her review of The Power of Makingexhibition. Her essay Why don’t we hate Etsy? shows a desire to cover the breadth of popular making culture with an open mind, eschewing hierarchies. While she is critical of the online craft-market, stating that the goods which are traded on Etsy can overwhelmingly be ‘categorised as giftware – or even clutter’, and referencing the Marxist concept of false consciousness in relation to the craft ideal Etsy sells its users, she shows an empathy for that ideal: one of an ‘autonomous life of craft’ combined with the promise of ‘durable personal relations in a world where these appear to be in short supply.’ In doing so, Harrod doesn’t dismiss the users or phenomenon of Etsy, merely the cynical capitalism that underpins it.

Bringing the political-economy that is in craft’s DNA – but which is often bellied by its fast-fading fusty image – to bear is one of the great successes of The Real Thing. Harrod quite consciously places her writings in the context of the destruction of social democracy and the dominance of ‘the relentless logic of neoliberal economics’ in a globalised world. Even a small news piece for Craft magazine about a Bethnal Green yarn shop starts and ends with ruminations on the Austrian theorist Ivan Illich’s political thoughts in relation to making – although, as ever, in a humane and accessible way. Harrod smuggles theoretical and historical debate into the most unlikely of places, the pill more appealing and easier to swallow under the guise of yet another exhibition or book review: and in the end it is the debate more than the review that stays with you.

The political foundations of craft weave throughout the essays of The Real Thing, just as they have throughout crafts’ existence as a theoretical entity: as an oppositional form of making to mass-production. A short biographical overview of Arts & Crafts book-binder T.J. Cobden-Sanderson tells us of how his turn to socialism coincided with his taking up a craft, and how both craft and politics were made manifest in his work at the Doves Press and the Doves Bindery. They were ‘prophetic expressions of things to come – when a socialist state would transform daily life with guilds revived, with joy in labour, with seasonal festivals and pageantry.’ While the revival of guilds and pageantry is low down the wishlist of most contemporary makers, Harrod picks up the threads of this Arts & Crafts ideology again in her review of The Power of Making exhibition at the V&A, where she sees that the displayed objects 'articulate a disdain for the exigencies of time and money. Thus they have a political dimension, playfully undermining functionalist economics, creating disorder in the world of work.’ The essay How to get money appears to be paradoxical – in a very Morrisian way – in its praise of wealthy collectors as the saviours of art and crafts; in a book that critiques the neoliberal structures that have allowed wealthy individuals to marketise and control the arts it is perhaps a rare moment of contradiction considering the period of time covered by these texts. Harrod’s critique of Richard Sennet's The Craftsman comes back to sturdier ground: The Craftsman lacks 'a recognisable political core', she states. Harrod is also effusive of the political legacy left by designer and theorist Norman Potter: ‘Potter was in the best sense creating something that was marginal and quietly disruptive’ – a good phrase for describing craft per se, perhaps.

This dismissive chipping-away of the old-fashioned idea that craft and making-culture is a safe, apolitical activity continually reveals craft’s true relevance today. With its inherent critique of efficiency-drives and the exploitation involved in many of the ‘McJobs’ on offer – where, as Ruskin would have it, people are treated as machines, not humans with agency – it provides both a utopian ideal (‘the autonomous life of craft’) and a practical retort. As Harrod suggests in her preface to this book, making is equivalent to ‘being true to ourselves’; the humanity of the well crafted – whether handmade or not – is a radical rejection of lowest-common-denominator design and manufacture employed by mass production. For the precarious worker, often used as an extension of their employers ‘brand identity’, to make their own object or tool or art piece is a radical statement of personal sovereignty from corporate life. It is the sane thing to do in a time of insane economic ‘rationalism’. The Real Thing, however, is far more than an explanation of making's contemporary 'fashionability'. It represents thirty-plus years worth of work, giving it a weight that allows it to transcend fashion and deal with the bigger questions about what drives humanity to keep making, and how that timeless act sits varyingly more or less comfortably into different eras of modernity and post-modernity. To borrow a phrase the ceramic artist and writer Edmund de Waal has used to describe his approach to his own making, The Real Thing is both ‘rigorous and humane’; a perfect reflection of something well crafted.

The Real Thing: essays on making in the modern world by Tanya Harrod

Hyphen Press, £20

hyphenpress.co.uk