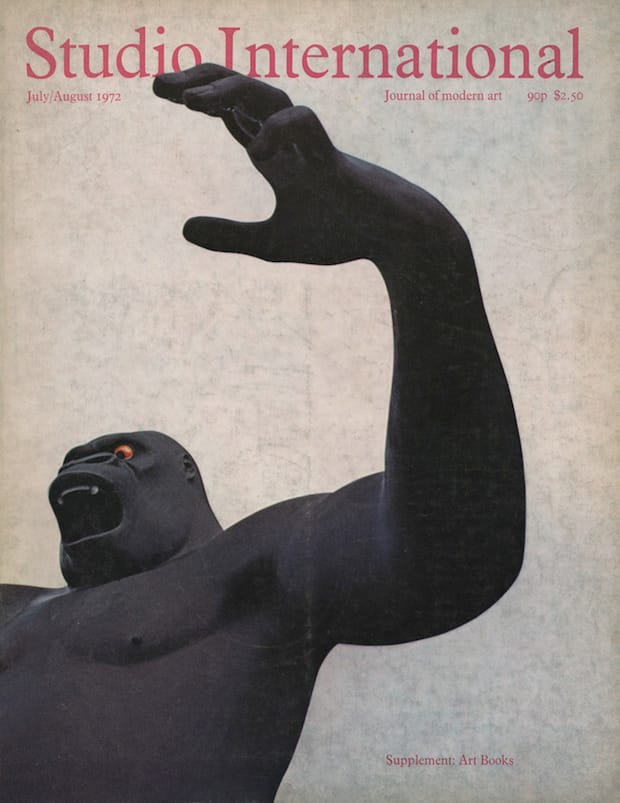

A new show at London’s Raven Row art gallery takes an exciting curatorial position by looking at the dialogues between 1960s and 70s radical sculpture and the art magazine Studio International.

Spitalfield’s art gallery Raven Row has opened its doors on its latest exhibition, Five Issues of Studio International. It's a fascinating look at mid-late twentieth century British sculpture through the prism of five selected issues of the art magazine Studio International from the period of Peter Townsend’s editorship (1965-1975). Townsend favoured sculpture as an art-form – in it he saw the medium most likely to promote social change in accordance with his socialist principles – and his editorship coincided with a time during which sculpture was the venue of much radical change and dialogue within the art-world, with movements such as post-constructivism, kineticism, minimalism and conceptualism all vying for critical attention.

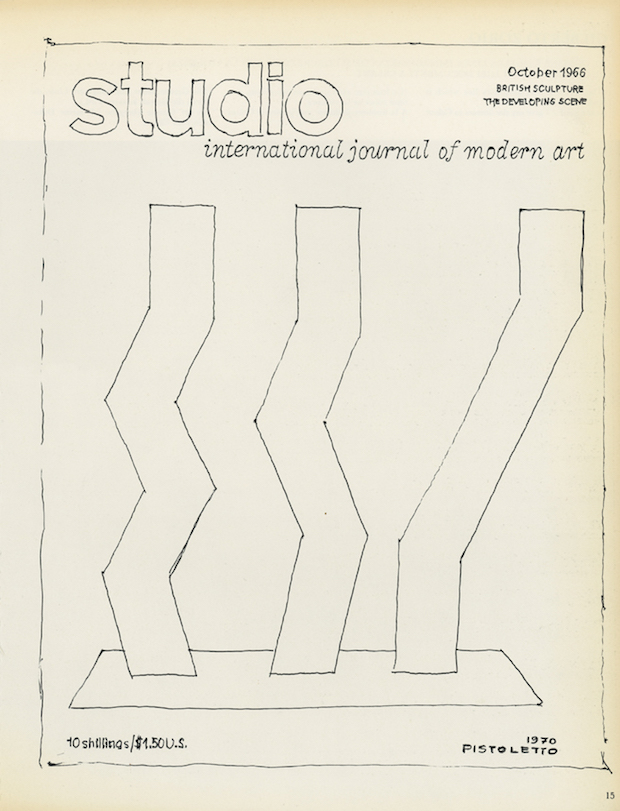

The excitement then felt of the new possibilities in sculpture is evident in the vital and experimental nature of what’s found on display at Raven Row; yet in her catalogue essay, curator Jo Melvin focuses almost entirely on the editorial exploits of Townsend. Seeing the show in the light of this essay lends it the feel of an exhibition more about the editorship of a magazine, looked at through the prism of its attendant cultural artefacts – from the sculptures featured on its pages to the original paste-up designs for the magazine – rather than vice versa. This distinction may seem unimportant but it can leave the sculptures feeling sometimes incidental, or illustrative. The facsimile pages later on in the accompanying publication provide an insight on to the sculptural work on show in this exhibition from its creators – and contemporary curators – but always in the shadow of Townsend’s editorial direction.

Studio International magazine itself started out as The Studio: An Illustrated Magazine of Fine and Applied Art in 1893, influenced by the British Arts & Crafts movement and continental Art Nouveau. Its first cover was designed by Aubrey Beardesly before he became well known – or perhaps, infamous – and it was instrumental in promoting the radical new work of British artists, designers and architects such as C.F.A. Voysey and Charles Rennie Mackintosh. It was with this lineage in mind that Townsend was entrusted to bring back a relevant, radical nature to Studio International. Rather than taking this as an opportunity to try and resurrect historical radical movements, he embraced the art contemporary to him, the fertile and international field of contemporary sculpture in particular, leading the magazine to the forefront of debates on art in its own time.

Delving further into his editorial approach, there is much of relevance that can be extracted and learnt from. According to Melvin, for Townsend the artist’s aims, where sculpture was situated and how the public encountered those sculptures were of equal importance. Here we get a glimpse of a man with a more than theoretical commitment to the radical potential of art — it is a refreshingly broad definition of the word ‘public’, as opposed to one that refers to the gallery-going ‘public’. Townsend was also self-effacing to a large extent: his only written editorials were for his first and last ever issues of Studio International, divided by a decade, and he often refused to acknowledge his own part in the interviews he conducted. He saw his task as quietly facilitating others and putting front and centre the content artists wanted, rather than positioning himself as the genius arch-curator of content, personalities and art, that so many figures in the art world attempt to do today. Townsend wanted the artists to do the talking, with as little mediation between them and the public as possible.

The designer of Studio International during Townsend’s reign, Malcolm Lauder, shared an office with the assistant editor and they arranged layout sheets together with Townsend, some of which can be seen on display at Raven Row, before sending them off to the printers where they would then check proofs as they came off the press. The thought of this level of involvement of an editor in the design process might send a shiver down the spine of some designers but one senses that with Townsend’s astuteness, and apparent desire for his magazine to take the form of some sort of Gesamtkunstwerk – or total, synthesised work – the design has only benefited from his input.

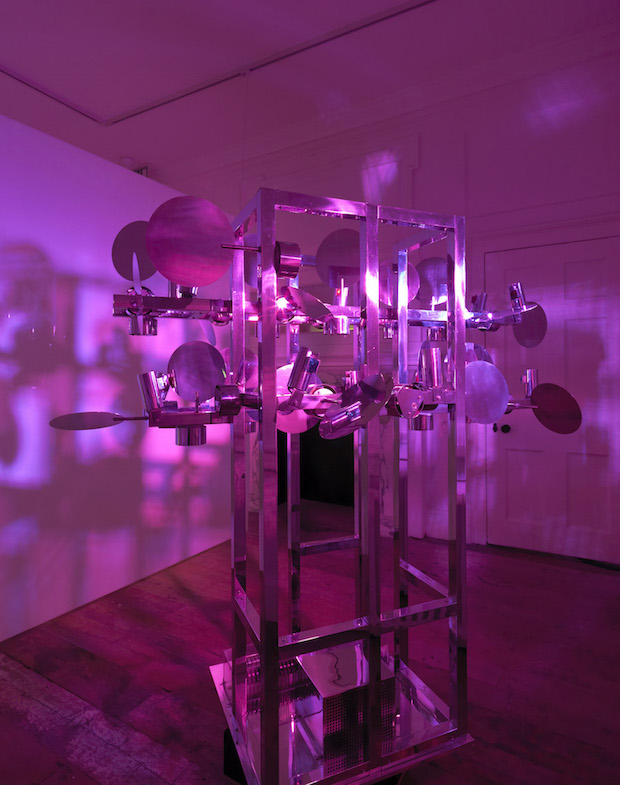

The sculptures themselves on display in Raven Row – and often reflected in the open pages of the Studio International’s being displayed in vitrines – range from Naum Gabo’s elegant constructivist and kinetic sculptures and drawings to the kinetic and cybernetic art of Nicolas Schöffer. Schöffer’s Chronos 10 (1962), all wiring polished stainless steel plates, psychedelic lights and projections – operating at fifteen minute intervals – is an evocative experience, particularly as a space-age juxtaposition to 6a architect’s quiet restoration of the eighteenth century town house that is now Raven Row. Barry Flanagan’s one ton corner piece (1967) has a topographical beauty while graphic designers will find plenty of highly relatable visual material beyond the displayed copies of Studio International in the form of Lawrence Weiner text pieces and other graphic displays from artist including Keith Arnatt.

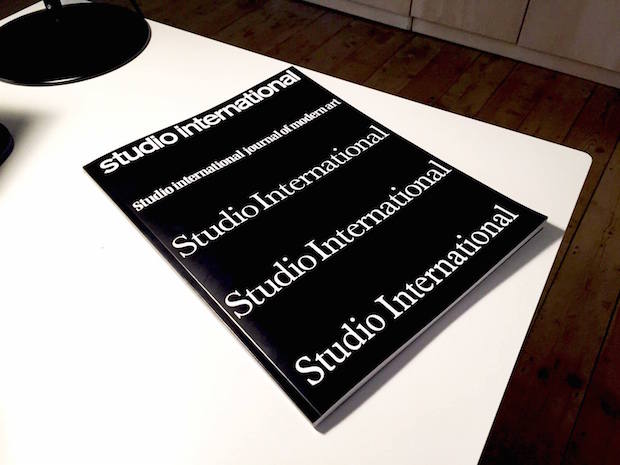

The accompanying publication, designed by John Morgan Studio, consists almost entirely of facsimiles from the five featured issues of Studio International, with the exception of a contents page and the introductory essay from Melvin. John Morgan Studio’s design allows the pages of Studio International to do the talking for themselves, with the modestly presented essay almost indistinguishable from the facsimile pages; and with a cover made up of the mastheads of the five selected issues of Studio International, the design is suitably as astute and self-effacing here as Townsend was in his editorship.

The curatorial process behind this exhibition provides an accessible way into both understanding more about a radical moment in British sculpture and an important figure in the publishing of modern art magazines. It also throws up some unexpected conclusions. The artist John Plumb, who designed the cover of the May 1968 issue, said of the commission that it was prestigious because far more people would see his work on the cover of Studio International than if it were in an exhibition. This hints at what, to me, is the unintended lesson of Five Issues of Studio International: that while Townsend favoured sculpture for its radical potential in public space, he was a master of the medium of print and publishing, and its radical potential surpasses that of abstract sculpture. The magazine itself is the real democratic art form here, a synthesis of design, art, criticism and editorial direction that has the potential to create, and in the case of certain issues of Studio International succeeds in creating, a piece of mass consumption total-art in itself.

Five Issues of Studio International

Until 3 May

Raven Row

56 Artillery Lane

London E1 7LS