On visiting anti-war artist Peter Kennard’s recently opened solo show at the Imperial War Museum it’s clear the photomontage work on display hasn’t lost any of its ability to shock over the course of the artist’s four-decade career.

Dodgy dossiers and panicked sentiment created by certain corners of the media: what it takes to justify armed military conflict in the twenty-first century. The voices against are few and infrequent, often marginalised and on the fringes of the discussion – portrayed as old hippies, reliving the Sixties (when it was cool to care). Where once the art world was full of the horrors of war and despair in humanity – from Otto Dix to Francis Bacon – it now largely just wants the good times to roll, so cozy is it with the financial elite that keeps the drinks flowing from private view to private view. Designers of an older generation, such as Ken Garland, Richard Hollis and Robin Fior, were able to successfully ingratiate themselves with politically radical organisations and to do important pro bono work for them – now the average freelancer struggles to find the time and struggles even more to persuade similar organisations of the value of their skills in communicating ideas.

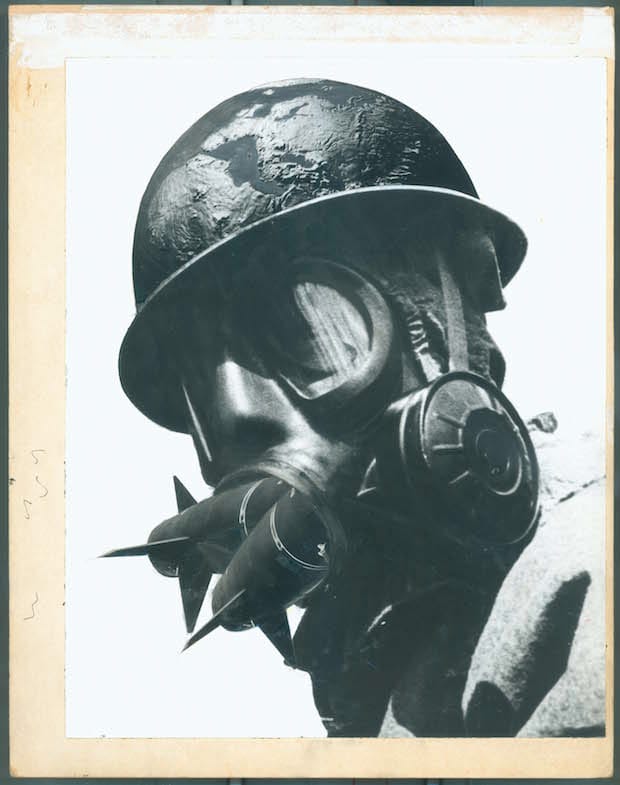

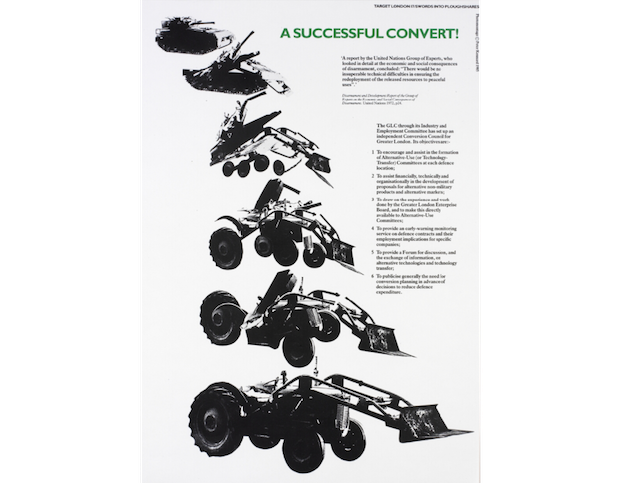

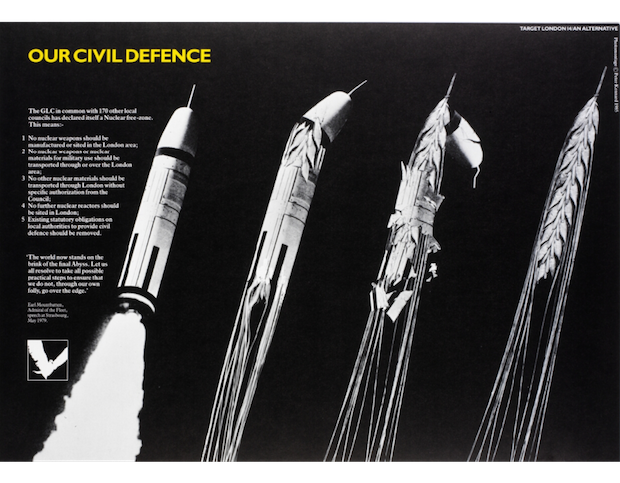

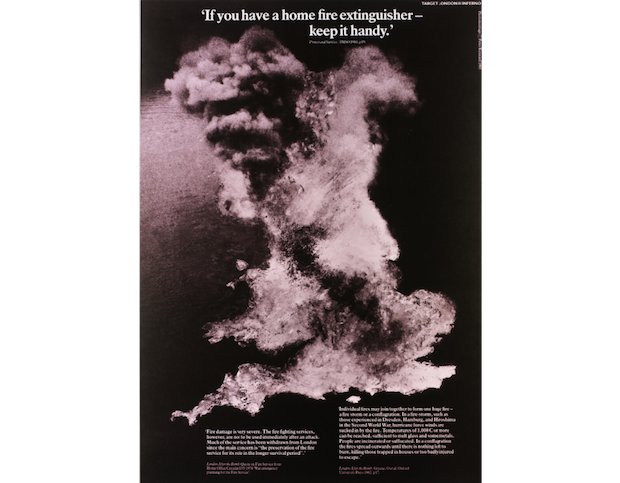

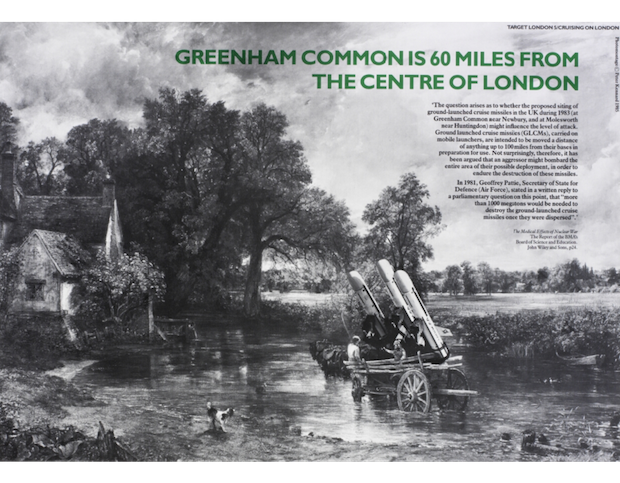

Through this transition from the Sixties to the present day, Peter Kennard has successfully kept alive protest in British art and design. His immediate, often crude and shocking cut-and-paste photomontages strike one in this exhibition as being, remarkably, as effective as they have always been. The majority of Kennard’s photomontages were created during the 1970s and 1980s, often for the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament and other pacifist or anti-nuclear entities: a poster for the Labour Party which shows a fist crushing a cruise missile most starkly shows how times have changed. In a room titled Archive – the most successful of the exhibition – we see not only these posters but other printed matter such as paperback books or leaflets adorned with montages by Kennard. A series of postcards with his famous image of the John Constable painting The Hay Wain altered to display a missile launcher crossing a peaceful Suffolk stream, as opposed to the traditional horse-drawn cart, showed the versatility of Kennard’s powerful images – the same design also features on several different posters and as a framed large-format original in the exhibition.

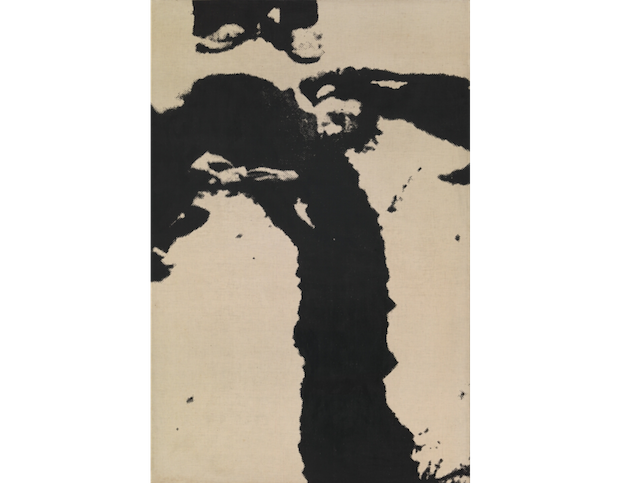

The problem with Kennard’s output, as evidenced in this exhibition, is his understandable and natural desire as an artist to branch out. After years of photomontages, covering issues from the war in Vietnam to the G8 meeting protests, Kennard has started to explore other mediums and formats for his work. These include works printed onto the financial pages of newspapers, a return to painting (Kennard’s preferred medium during his university days), and installation pieces which amount to three-dimensional photomontages. Commendable as all these works are, they lack that vital aspect which makes his earlier work so powerful: it’s not shock-factor but the democratic medium of the poster, books or pamphlet upon which they were printed. Works designed to be hung and installed in a gallery simply feel too passive for such urgent and prescient messages.

Kennard’s use of hand cutting and sticking is a wonderful example to a generation that has grown up with Photoshop. There’s a definite craft to the way he’s created these images but the fact that they are done largely by hand renders them just crude enough to stand in stark opposition to the sleek photomontages created by big business in order to sell soft drinks or a new television series. The juxtaposition created by this year-long exhibition of Kennard’s work being held in the Imperial War Museum is also something to celebrate: the war planes hanging from the ceiling of this institution offer some kind of true context to Kennard’s work which any other white-walled gallery space could not.

As mentioned recently in another article I wrote for Grafik, it’s arguable that too much of contemporary self-initiated and pro bono design tends towards containing surface-level content or a feeling of do-gooding; with people rarely getting their hands dirty with the politics of it all, beyond the politics of ‘it’s nice to be nice’. If there were contemporary designers or artists creating work of half the importance, impact and prevalence of Kennard’s, that would be a comment that wouldn’t need to be made. Kennard’s work is shocking and likely to be a bit of a downer when discussing it at a dinner party but the work itself reminds us that there are bigger issues to worry about. Practitioners have to make a living and shouldn’t feel they should do endless pro bono work, but when things like the Trident nuclear weapons system and human rights legislation are up for discussion as they are now – and the standard of debate in the media doesn’t match up to the importance and significance of the issue at hand – the voice of designers is an important one that feels lacking. Peter Kennard shows the way.

Peter Kennard: Unofficial War Artist

Until 30 May 2016

Imperial War Museum London

iwm.org.uk