Starting out with her first 35mm camera, lighting up the chalice and getting married at Sugar Minott’s house – photographer Beth Lesser shares memories of her time at the heart of Reggae and Dancehall.

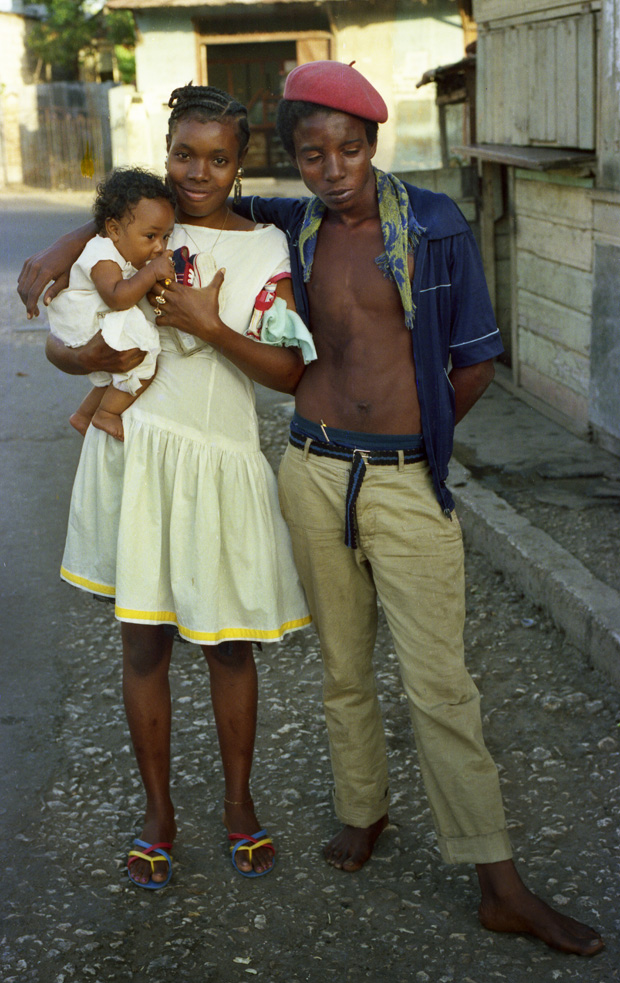

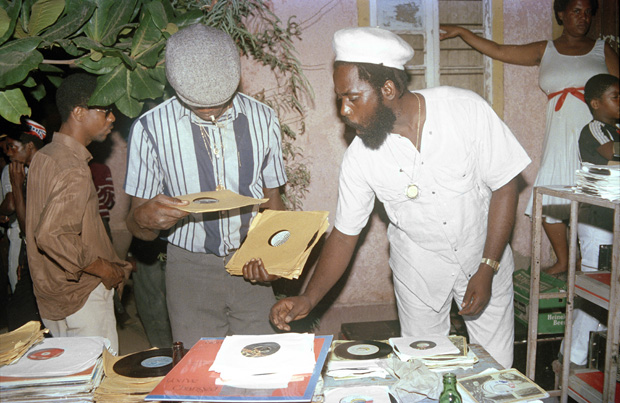

Photographer and writer Beth Lesser spent much of the 1980s in Jamaica, travelling with her radio producer husband David Kingston, immersed in and photographing the Reggae and Dancehall scene. It captivated her and defined her development as an artist. As well as producing a body of photographic work that provides an intimate survey of an important musical movement, Lesser was its unofficial scribe and chronicler, through her magazine Reggae Quarterly.

In this exclusive interview with Grafik, Lesser recalls the highs and lows of her time in the heart of Reggae and Dancehall, and talks about how it has shaped her life, loves and work.

Could you describe the special qualities of Reggae and Dancehall that initially caught you in to that world?

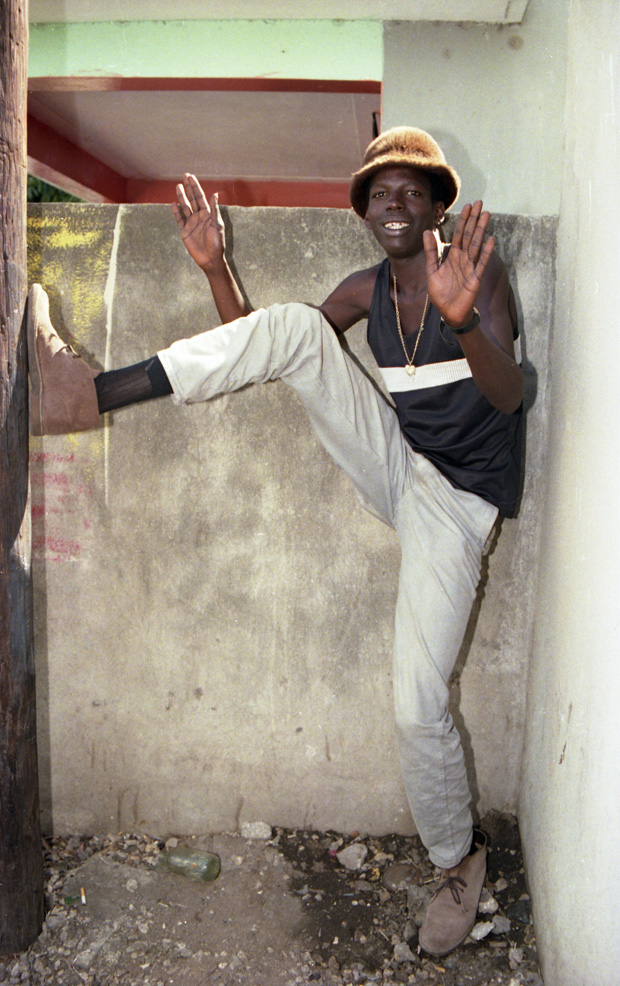

The energy, the humour. Sure, rap and hip hop had energy, but the artists took themselves too seriously. Reggae always had a lighter side that I didn’t see in its northern incarnations. Dancehall was about having fun. Besides, reggae is supremely musical. And creative, innovative, always trying something new. The many layers of the rhythms, the echo, the syncopation of the percussion. And the divine vocalists. The music sounded so fresh to us after the energy of the 1970s faded into the jaded sound of the post-punk synthesizer bands.

You documented the scene for a decade in the 1980s — how did you change as a photographer in that time?

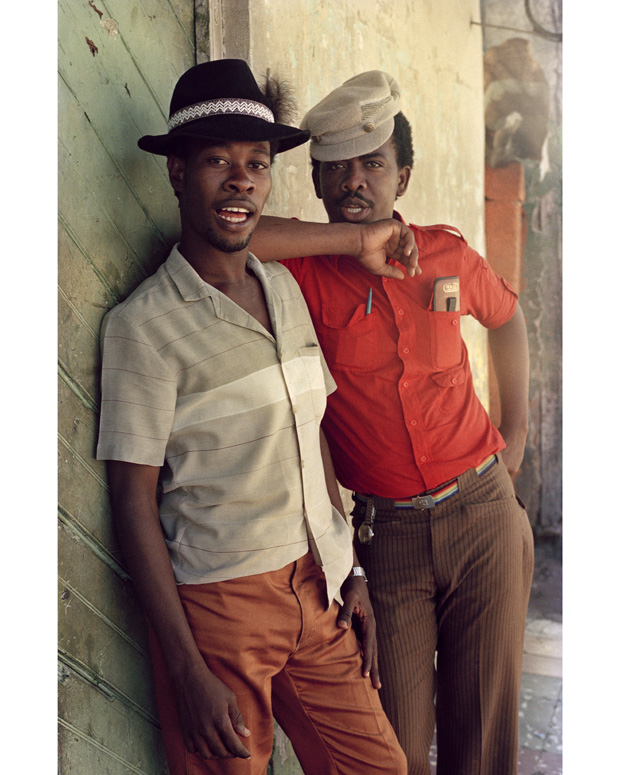

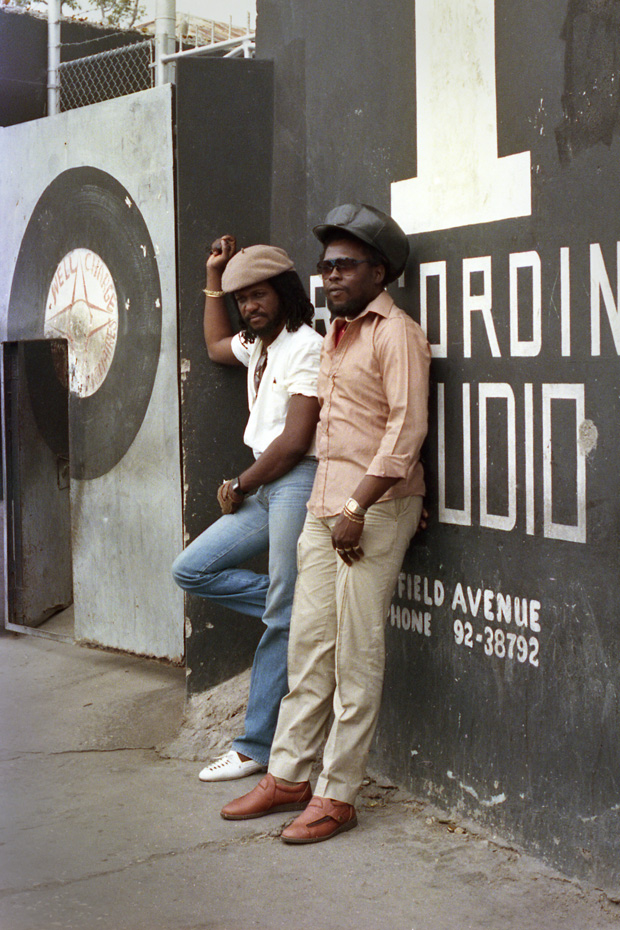

I basically learned the trade by taking these photos. I started out with my first 35mm camera, a 50mm lens and black and white film and gradually began to add different lenses, changed to colour film, started using a fill flash (I never got the hang of a stronger flash). And I became more interested in documenting everything, not just taking portraits of artists, but taking shots like the deejays gathered around the mic, performing at the sound system session, or the whole crew loading the boxes onto the truck to drive out to the next dance, or inside the pressing plant making records. And portraits of random people we came to know in our hours of hanging around and doing nothing.

Your work clearly conveys the charisma of the characters – could you share some favourite moments with them?

Thank you. I’m glad you noticed that charisma. Jamaicans are the most fascinating, infuriating, intriguing bunch of people. I’ll never forget Prince Jazzbo threatening to come to our wedding in a crocus bag because he was a poor sufferer. Jazzbo used to show up at our door at the first cock’s crow and complain that Canadians sleep too long when he found us still in bed, claiming he had been on the road for hours.

Despite the poverty all around, we found Jamaicans to be generous and happy to give. When we visited General Trees in his home base of Drewsland, he took us round to his shoe shop and gave me a pair of sandals he had made. I still have them. King Jammy actually loaned me his camera when mine broke one year.

What I remember most were the daily scenes in the Youth Promotion yard with Sugar rising late after a night of ‘bleaching’ (staying awake) in the studio or at a dance, lighting up the chalice and disappearing in a cloud of smoke. Kids were climbing trees, running all around. The clan included several of his own children along with his young apprentices like Yammy Bolo and Little Kirk. Laundry was being hung, food prepared. Artists would drop in and sit and have a lick of the chalice. Sugar [Minott] made sure all his artists got their draws of weed. He would cut it in the yard and hand it out to a crowd of eager youths. Smoking weed went on everywhere, even inside the recording studios while a session was going on.

On the other hand, there are lots of adventures, like the time a youth came up behind Dave and grabbed his gold chain, and we went driving out with the neighbourhood don to track down the thief. Or visiting King Tubby in his studio in Waterhouse (and crossing the dreaded gully from King Jammy’s studio with Ray I).

I’m hoping to create an interactive platform for the internet where I can post all these photos and the stories that go with them. But I’m not sure how to go about that.

How were you, as a white Canadian woman, received by the Reggae community of Jamaica?

I think the fact that my husband and I traveled and worked together created an entire unique dynamic. David was collecting material for his radio show, a show on which many of the artists appeared when they passed through Toronto, and I was taking photos and doing interviews for Reggae Quarterly magazine. Obviously we weren’t there for an exotic fling, or to rip people off.

Since neither of us knew how to drive, we traveled around on the minibus, looking pretty inoffensive and non-threatening. The fact that we got married at a Youth Promotion dance at Sugar Minott’s house (and invited everyone) helped our credibility, I’m sure. We were there for the music and we took the music very seriously.

That being said, there was always the occasional man who, when given an issue of the magazine and addressed by me, would look straight over my head and respond to my (much taller) husband and ignore me completely.

You have completely immersed yourself in the Reggae and Dancehall cultures, and published 'zines out of it. Do you think there is anything equivalent to the energy of Dancehall at its heyday today?

I guess I’m not as in touch with what is going on today. After all, it’s not my music anymore. It’s for the kids, for the younger crowd. It’s not even supposed to appeal to me. Quite the contrary. I suppose the current music sounds to me the way Dancehall sounded to all those great old Ska musicians. How dare these kids call little keyboard ditties ‘music’ after they spent years mastering complex instruments? And they were right. Dancehall was nothing like the music was the Ska days. But, at the time, we felt the energy of Dancehall and just allowed ourselves to be pulled along with it happily.

I think the big difference is that now everyone can self-promote. Back in our day, it took a journalist to go down to Jamaica with a camera and tape recorder and capture the scene and then put it out somehow – in a magazine, on the radio – get the information out. With the internet and Facebook, every small artist can create his own publicity, get his own music out there, create an online ‘zine’ or blog about himself. Back then, we were those middle men between the music and its audience. But we are no longer needed.

Beth Lesser's work is currently on show at KK Outlet in London, 6–30 January, 2016.

Find out more about Beth Lesser here.

Read about Beth Lesser's work in the current issue of Riposte Magazine.