Subversive, satirical and even sexy, the British Library’s new exhibition Comics Unmasked explores the most important fruits of the UK comics scene and the counter-cultural movements that germinated them.

Being a teen in the late 80s and early 90s entailed coming of age at a distinctively fertile period in comics history. For me, as for many, Tim Burton's Batman movie was a gateway to some of the broader, stranger material indicative of the era: Alan Moore's pioneering run on Swamp Thing, Grant Morrison's two-fingers at the traditional superhero team book, Doom Patrol, and, of course, the gore-stained and viciously funny science fiction weekly 2000AD, at that point riding high on a wave of excellent stories and characters. Aside from their roughly contemporaneous publication dates, these iconic (and radically different) titles share two more attributes in common – attributes that also define The British Library’s new exhibition Comics Unmasked, the largest show of comic art ever seen in the UK. Firstly, all of them are wickedly subversive. They’re rude, occasionally obnoxious and mainly concerned with thumbing their noses at those in power; whether it be the political establishment or the market-dominating American superhero comics that were rapidly sliding into empty posturing at the time. Secondly, their creators were all British.

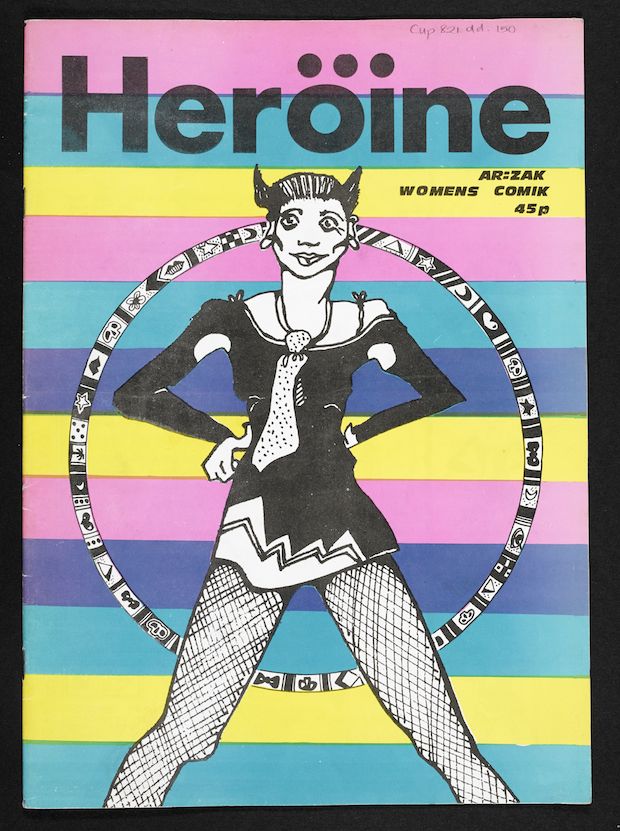

Of course, the insurgent attitude so prevalent in the British comics of the late 80s and early 90s was nothing new, and the curators of Comics Unmasked – writers and experts Adrian Edwards, John Harris Dunning and Paul Gravett – have assembled an impressive array of rare books and artwork stretching back to the 19th century. They aim to prove that disobedience has always been integral to the unique DNA of British comics – from the satire of Punch to the complex psychogeographical musings of Laura Oldfield Ford's Savage Messiah, and that the form is as inseparable from rich counter-cultural peaks as ink from panel borders. Comic art is a reckless current that’s always ready to lurch into unexpected territories with each new generation of creators.

With this in mind, the exhibition has been organised into six separate sections, each focusing on an social or cultural theme. It opens with 'Mischief and Mayhem’, which explores violence in the genre, from Mister Punch to 2000AD's controversial precursor Action, a comic given the ultimate accolade of being condemned by the House of Lords. It’s followed by rooms dedicated to minority voices, political engagement, and (housed in a big pink tent, away from the main exhibition and thus skippable for the easily offended) sexual subversion. Though all of these opening sections contain a fascinating wealth of books and materials (some unknown to even a dyed-in-the-wool geek such as myself – how had I never heard of the extraordinary gay pop-art erotica of Bill Ward before?) and make some interesting points about the evolution of the comics form in the UK, it is difficult to get away from what is being presented here: it's a collection of books. Some old, some rare (and some not, I found it hard to get too excited about an issue of Hellblazer I've owned for nearly twenty years being put behind a glass cabinet), but all slightly static. Attempts have been made to add some dynamism – there are dummies made up as protesters wearing V for Vendetta masks for example – but some more interactive elements would have made a big difference. The material sings, and much of the art on display is of a magnificent standard, but it is difficult to glean much sense of comics as a living art form from the opening rooms.

All this changes with your arrival in the fifth section. 'Hero With 1000 Faces' focuses on the scene's love for the unconventional hero figure and the exhibition suddenly explodes into a technicolour riot of original artwork, scripts and breakdown pages. Fanboys and girls will delight at the range of geeky ephemera, from the actual helmet Carl Urban wore in last year's Dredd movie to a stunning page of fully painted artwork from Simon Bisley's Slaine: The Horned God. There were a couple of pieces of work I spent an inordinate amount of time cooing over. The first was an original un-inked front cover for Grant Morrison's Batman and Robin by the great Scottish artist Frank Quitely, a meticulously drafted work that may go some way to explaining why he occasionally seems to have such difficulty meeting his monthly deadlines. Secondly a page of Steve Yeowell's artwork for Morrison's Zenith, which is alive with impenetrable inky blacks and stark slashes of negative space and proves beyond doubt that British comic artists were way ahead of the pack when it came to absorbing the influence of Japanese Manga.

A final section tackles the UK comics scene's obsession with altered states, from the drugged science fiction of Brian Talbot’s Luther Arkwright to the woozy surrealism of UK psychedelic musician Alex Tucker's Shandor. Also laudable is the curators’ decision to approach their subject laterally at times. British comics indelible cross-fertilisation with magick is well known amongst fans, with Alan Moore and Grant Morrison both having declared themselves Magicians during their careers, but it is fascinating to have the connection explored via a selection of Aleister Crowley's notebooks, as well as one of Elizabethan mage John Dee's Magickal grimoires. It's an association that won't be obvious to a lot of visitors to the exhibition and that throws interesting light on the rest of the exhibits.

The very fact that a show like this is being held in such an august space as the British Library bodes well for the health of the British comics scene, with new writers and artists such a Kieron Gillen and Jamie Mckelvie already earning their spurs in the international superhero market. A selection of webcomics near the end of the exhibition also goes to show how astonishingly adaptable the form is and where it can go next. However if there is one message that the exhibition carries throughout, it is that this marginalised art form, cheap to produce and immediate in impact, is one of the best ways for the voices of the marginalised to make themselves heard. That's why the urge to create comics will never die, and also why they will always remain so vital. Comics Unmasked: Art and Anarchy in the UK

The British Library, London

2 May – 19 August 2014