What became of the "Workshop of the World"? London’s Science Museum hosts a fascinating, if flawed, investigation into the health and happiness of the UK’s industrial sector.

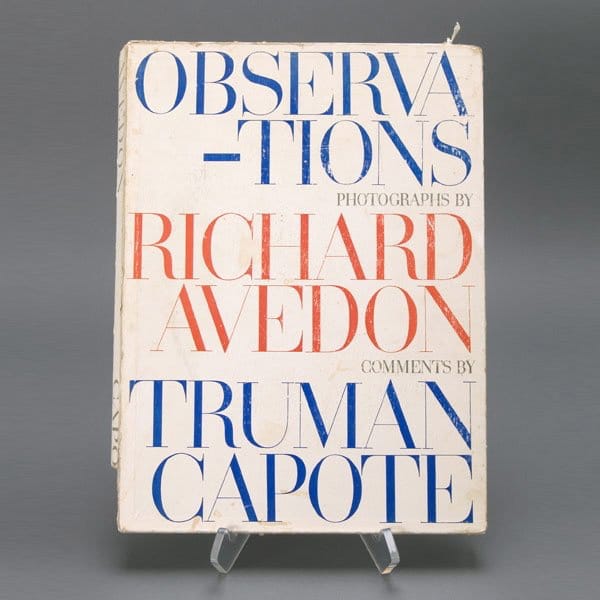

As a genre, industrial photography’s evolution has wavered alongside cycles of growth and collapse, as well as the shifting make up of modern economies; it is not a field with much room for ambiguity, the photographer often having to define their position from the outset, due to issues of access and intent. During the mid-20th Century productive boom many of the great practitioners of industrial photography were employed by the companies that they were cataloguing, and so, their relative aesthetic strengths have to be read against a skewed agenda. Esther Bubley’s photographs for the Standard Oil Company — “character” images depicting the American man at ease within his machine environment — are a case in point; as are Maurice Broomfield’s dramatically (but artificially) lit quasi-surrealist images for Imperial Chemical Industries. During the same period, weekly photojournalistic magazines such as Life provided an outlet for industrial photography with a human-interest angle – just prior to joining the staff, one of that title’s chief photographers, Margaret Bourke-White, commented of her own evolution from the mechanistic to the humanistic: “While it is very important to get a striking picture of a line of smoke stacks or a row of dynamos, it is becoming more and more important to reflect the life that goes on behind these photographs.” As we’ve shed the naive belief in a particular neoliberal vision of progress, industrial photography has taken a critical turn, highlighting the environmental and social catastrophes inflicted by multi-nationals as part of often protracted, research-led investigations – think Richard Misrach and Kate Orff’s Petrochemical America or Eirik Johnson’s Sawdust Mountain – and are increasingly the preserve of fine artists as opposed to photojournalists or visual anthropologists.

Open for Business at London’s Science Museum extends the history of industrial photography by instigating a kind of celebrity group workshop. In collaboration with photographic co-op Magnum, nine practitioners have been dispatched throughout the island to capture what they can. The majority are natives, such as David Hurn, Stuart Franklin and Martin Parr, though three international photographers, in the form of Alessandra Sanguinetti, Jonas Bendiksen and Bruce Gilden, offer perspectives unclouded by any form of national sentiment. The premise of such an exhibition is conflicting – the need to promote something that has become largely invisible, if not disappeared entirely, acts as an indicator of how far it now is from public view. The title is appropriate in this regard, being the sort of assurance chancellors proffer at the low ebb of a recession. (Indeed George Osborne used the shibboleth on several occasions during the worst of the recent finical crises). It usually translates as an unconvincing gesture that “despite appearances, we’ve not been gutted.”

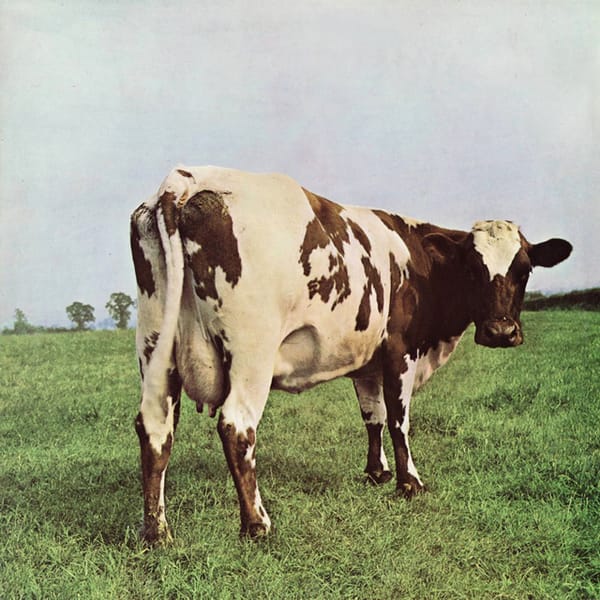

Open for Business’s accompanying literature invokes the spirit of Joseph Wright and LS Lowry, two painters who catalogued different periods in Britain’s manufacturing history. Wright’s paintings are heroic portraits of man at work, celebrations of the origins of Britain’s industrial might during the latter half of the eighteenth century; Lowry’s popular landscapes are somewhat different – faceless figures, small and stiff against the repetitive backdrop of smokestacks and blandly rectilinear buildings – they show that hardship as well as heroism was formative in those tough working communities whose ethos is extrapolated as being particularly of this nation. In the 1950’s, when Lowry was creating much of his most famous work, Britain was an industrial force – in 1952 manufacturing accounted for a third of national output and forty percent of employment, figures which fell, as of 2013, to eleven and eight percent respectively. It’s a poignant time, then, to visit an exhibition devoted to what remains of Britain’s manufacturing reserve. What Open for Business sets up is an opportunity for several of the world’s most talented practitioners to test the effects of these shifting parameters.

The images are the result of a brief, executed over a set (relatively short) period of time, and with a definite end-point in the form of an exhibition. While there was likely no rule as to tone or spin, the title deflects from most forms of serious or unbiased investigation. As a result, the show is a perplexing mix of styles and approaches, ranging from straight-faced documentary to tongue-in-cheek formality to wilful aestheticisation. On the one hand, this robs the show of any coherence or useful insight, but on the other it forces a collection of photographers, under the moniker of an organisation not best known for experimentation, to move a little beyond its comfort zone.

When Stuart Franklin went to photograph the Rosyth shipyards currently building the HMS Queen Elizabeth it struck him as a Lowry-esque anachronism, like a “scene from the 1950s”, with its onsite community of workers tramping in and out of the yard in ever-rotating shifts. The key image, however, taken from the deep [is ‘the deep’ a term, or should it be ‘from deep within’?] within the dry dock, bulbous bow thrusting towards the lens, communicates a sense of mass, both of the ship itself and of the enterprise of building it.But none of the builders are in shot; human figures are also absent, by nature of their operation, from his photograph of Whitelee Winfarm and Pelamis Wave Power. Though the Queen Elizabeth’s abandonment is a myth of the photograph, and the sustainable energy plants are fully automated, these oversize black and white prints portray a misanthropic industrial landscape that feel like they play with historical scale as much as pictorial, perhaps showing a future age – the post-anthropocene.

Franklin’s images stand out for their pictorialism and poeticism, as well as their willingness to conjecture on a monumental scale. Elsewhere, the point of concentration is closed within the interiors of production, on the people that reside there and things they manipulate. This works best in the case Mark Power’s photographs of Bombardier and Camira Fabrics, consciously overemphasising an enveloping darkness (which works against itself in the aggregate display in gallery but well individually) from which the camera appears to emerge. If this sounds slightly malevolent, it is, especially when the lens approaches from below and behind towards the victim’s feet. These are highly controlled pictures, quite unlike Power’s Dignity of Labour series from the early 90s, which had a far more overt violence about them. This kind of undefined disquiet, though indecipherable, was very welcome in an exhibition that often lets the quotidian fall into the humdrum.

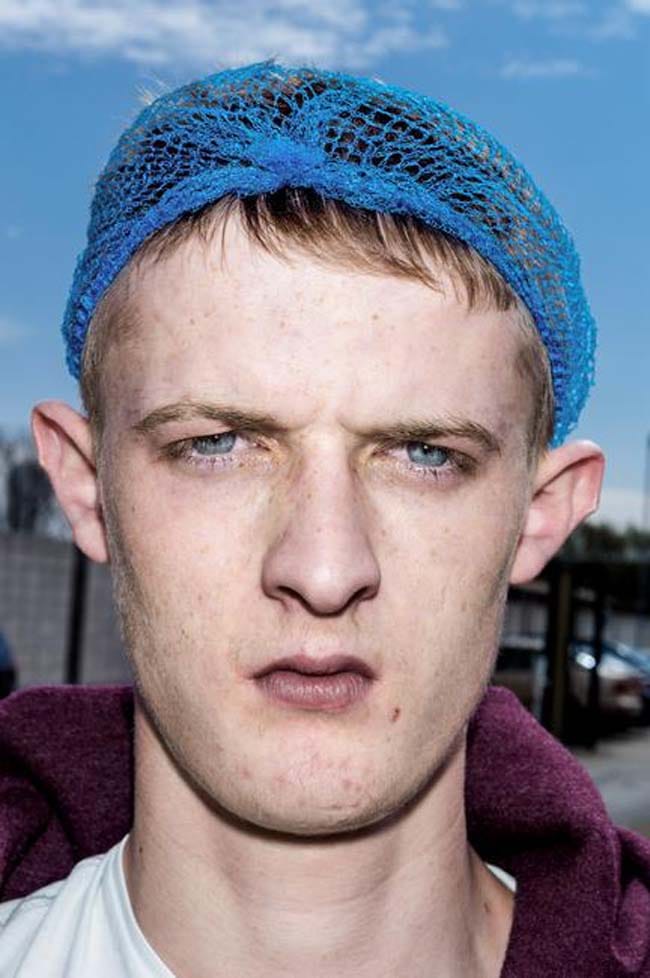

Chris Steele-Perkins provides the largest body of images in the show, most often utilising the stagey group shot, his subjects appearing from behind corners, between boxes, or bored in the conference room. In one, four men who make mattresses are draped provocatively in lengths of encased coil springs; in another, four more men, yacht builders, appear through the gaps in a wooden blank like choral extras in a budget production of Westside Story. It’s neither enlightening nor edifying. Similarly ill at ease are Bruce Gilden’s portraits of employees from both the Tate and Lyle sugar refinery and a Vauxhall car production plant, not because they are bad portraits – though this sort of close proximity, hyper-realist reproduction does anyone who has not had professional attention a disservice – but because they lack any meaningful context or inference within the setting of the show. Gilden is a portraitist and street photographer by trade, but these carefully demarcated profiles lack substance, even if it nice to see him working in colour for a change.

Decontextualisation has always been something of a visual tick in this photographic genre, the severe crop or the close-up, but mostly in reference to the hard and soft surfaces of capital goods, purloined in order to create beguiling but meretricious abstract compositions (cf. Charles Sheeler). Steele-Perkins goes for the soft: a pile of wide rubber belts, the ravines in an unsmoothed expanse of adhesive plastic sheeting, the pleasantly farcical dissemination of sausage meat. But it is Peter Marlow who really layers it on hard, turning Casting PLC, Kirckpatricks foundry and Angel Ring into indistinguishable set shots from an apparent Ridley Scott sci-fi epic, all steam and steel angles. These are arresting images unbridled by any useful information about the subject they were briefed to explore.

In antithesis to this is the work of Jonas Bendiksen, whose subjects always feel located accurately and unselfconsciously within the physical and mental location of their work. The camera operates silently, close or far, as if the employees have arrived in front of it instead of it in front of them. Depth of field is manipulated to locate action without fetishising either human or architectural form and colour is elevated to take advantage of these chromatically fascinating environments without feeling contrived. There is also an important dialogue between images, even spanning the ten different companies Bendiksen visited (mostly textile based), that is beyond most of the other commissions. This rapport sees a study of a wool dyer’s powerfully curled arm contrasted with the calendars of gym puffed bodies that surround the desk of an employee at a bed manufacturer, or a cafe owner glowering above his counter, on the front of which read the words “keep smiling” in florid calligraphy – he stares resolutely out of shot, maybe towards the man in the rubber gauntlets stirring a vat of noxious chemical in an opposing frame. For much of this exhibition you are left searching for a consequential statement as to the subject at hand: in Bendiksen’s work we get tantalisingly close to something deducible – a hopeful sense of communality, even if built around shared difficulties.

We’re no longer the “Workshop of the World”, but we knew that already. Our facilitates don’t look to be the most cutting edge, though our workforce appears (or is portrayed) as being as dogged as you might expect, game to fight against the worsening odds of global commerce, proud of their part in the economy and confused as to why they might be deserving of the attention of a Magnum photographer. They are likely too busy grafting to consider their increasing rarity and commensurate value, not just as a reservoir of a certain model of Britishness as tied to industry, but also as an image that can be co-opted to present Britain back to its now largely metropolitan self in manner that it still finds pleasing, though increasingly inaccurate. Open for Business

22 August – 2 November, 2014

Science Museum, London

sciencemuseum.org.uk