GraphicDesign&’s new book Graphic Designers Surveyed gives a fascinating glimpse into many aspects of the UK's design industry, and reveals that the gender gap isn’t restricted solely to the contents of designers’ monthly pay packets.

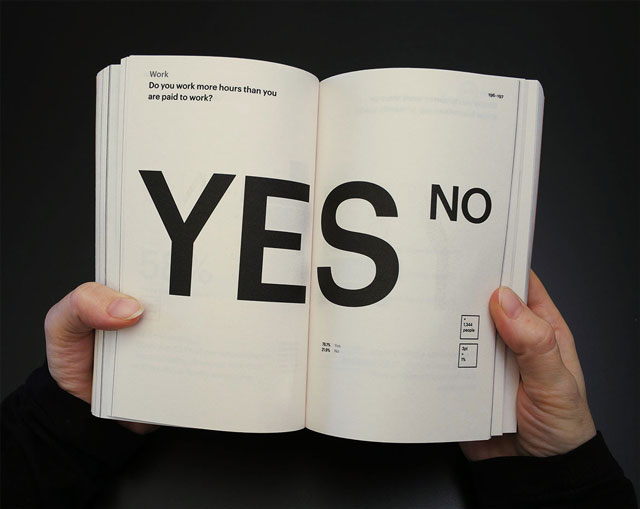

While it shares the same paperback format as the publishing house’s first two titles, GraphicDesign&’s new book is quite a different offering. Graphic Designers Surveyed is based on a survey of over 2000 graphic designers carried out in early 2015 in the UK and the US. Along with social scientist Nikandre Kopcke and information designer Stefanie Posavec, GD&’s Lucienne Roberts, Rebecca Wright and Jessie Price have attempted to make sense of the huge amounts of data collected, and the results are this fascinating and fact-packed book, which reveals considerably more about graphic designers than any Design Council survey ever would.

The book is an interesting read on many levels. The editors have taken their task very seriously, and there’s a great deal of transparency in terms of the methodology used, which is refreshing given the ambivalence most of us now have towards surveys, due to the majority being used a PR-vehicles to tell us something which we already know, or if we didn’t know it we didn’t have much interest in anyway. As you might expect, getting graphic designers to do as they’re told is always going to be problematic – in her introduction Kopcke reveals that “Graphic Designers are a nightmare to survey. They frequently disregard instructions and give answers that can best be described, fittingly, as creative,” adding that “Male designers tend to be both creative and grouchy.”

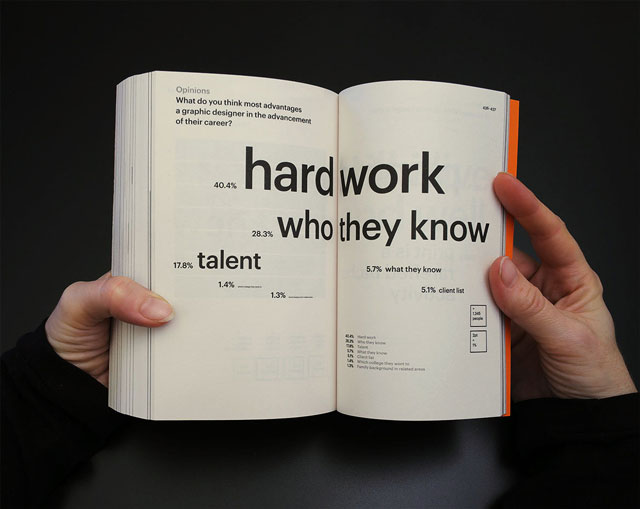

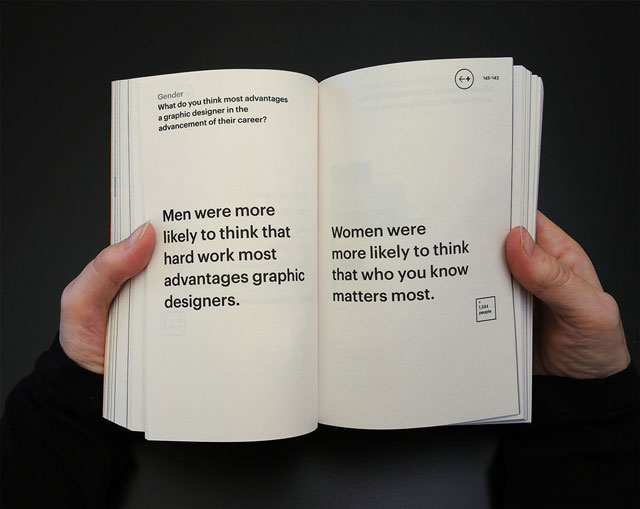

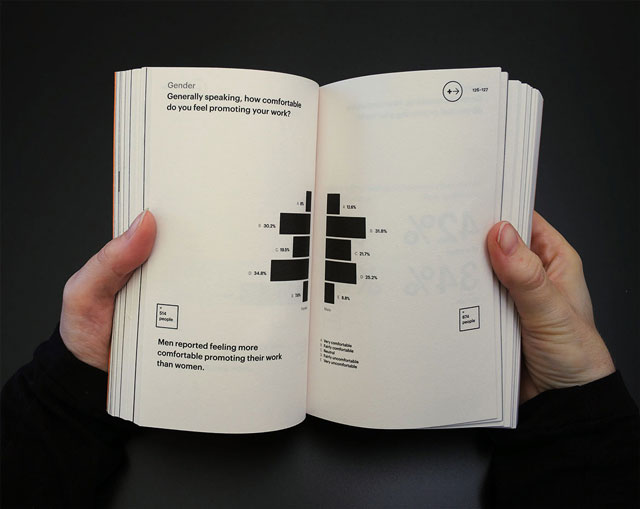

The differences between male and female graphic designers is a theme which recurs throughout the book, not just in the section devoted specifically to gender. So what does this book reveal about this particular topic? For a start there’s the significant pay gap (which widens with age), and the fact that women were less likely to speak about their work in public and felt less comfortable promoting it – none of which come as too much of a surprise. More telling is perhaps the statistics showing that the majority of women believed that the graphic industry is a masculine culture (whereas most men saw it as gender neutral), and that while men saw hard work as the most important factor in success, women felt that it was down to who you know, which might suggest that women see graphic design as being akin a club which they don’t belong to.

As Kopcke notes “This book tells us about the group of people we surveyed, but for the most part the results shown don’t tell us why things are the way we are”. It’s well known that there are many more women graphic design graduates, but very few women at the top. Kopcke states that this is true of every industry, so we can only assume that it’s down in the main to either there being less opportunities for women to progress, women being less ambitious or women entering but then dropping out of the industry.

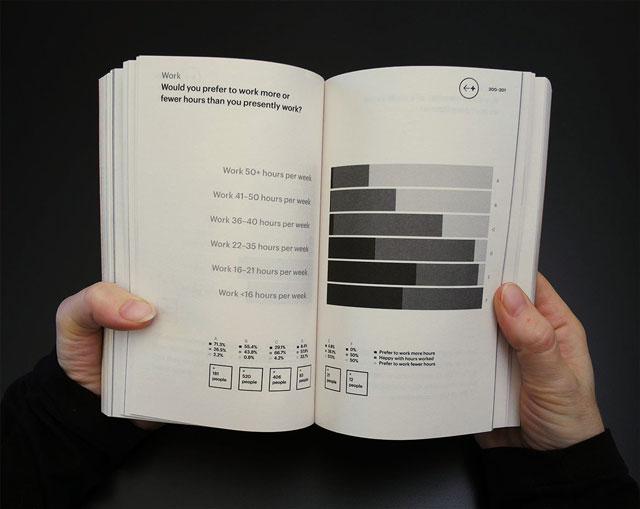

This is the point where the ‘C’ word rears its head – having children tends to have a profound effect on womens’ careers, whatever industry they work in, for a number of reasons. Even though no one would dare admit it, companies may be wary of employing 20- or 30-something women given the year-long maternity leave that’s now become the norm. It’s interesting that men are not taking more than a couple of week’s paternity leave – it could be because they think it might damage their career, they might earn more than their partner receives in maternity pay, or it could simply be that they’d rather be at work than chasing after an energetic toddler all day. While the glossies might be full of ‘mompreneurs’, unless you are married to a hedge fund manager and/or have a full time nanny, the reality for most people combining work and childcare is somewhat different. Despite men playing a much bigger part in their childrens’ upbringing, it would still appear that women tend to take up the slack as far as school pick up, doctor’s appointments, after-school activities etc are concerned. It would seem that some companies are reluctant to offer a part time or flexible option – probably because the culture of working long hours would still appear to be rife within the design industry.

Perhaps this is why women often move into roles within design companies within which are more likely to be part-time, such as new business, HR, office management and PR? It’s interesting to look the gender spread within companies. While there are often women in ‘support’ roles it’s still fairly rare to find companies with equal numbers of men and women designers at both junior and senior levels. Is this due to practical or cultural reasons? As GD&’s Jessie Price points out, “If 48% of women working in graphic design think that their industry has a masculine culture, how might that affect how they see their position in it? There is obviously a difference between a man feeling he works in a masculine culture and a woman thinking that she does.” Things like company culture are hard to quantify, but maybe women designers simply aren’t going to be attracted to an environment which has an overtly blokey culture, and thus the situation remains the same.

So what’s the solution? One step would be for companies to really embrace the idea of flexible working and end the long hours culture that involves all their employees (male and female) working many hours for free. This would almost certainly involve upping fees though, which means that keeping designers at their desks until way past their kiddies’ bedtimes is likely to remain the preferred option for many studios for the forseeable future.

Might things be different if more women were in charge? While there are many women very successfully running their own studios it would appear that there are still considerably less women doing so than men. Perhaps this is because the long hours and responsibility of running your own studio would appear to outweigh any gains in flexibility? If there were more women at the top, would there be more women in senior positions?

The idea of positive discrimination doesn’t always sit well with those who haven’t personally experienced barriers being put in their way. Kate Moross comments in an article in Design Week: “I’ve pushed back against this ‘women in design’ thing – I’m not a woman in design, I’m a designer. In the case of my own practice I’ve never feel like I’ve struggled because I’m a girl in design.” She then admits that the fact that there are so few high profile women designers has had its advantages: “But I’m also lucky because there are so few women designers out there – so there are about six of us that get invited to do all the talks…”

There is a growing awareness that women need better representation across conferences and events, with sites such as ‘Congrats you have an all male panel’ using humour to highlight this, and various sites which house databases of female experts., giving event organisers no excuse to leave them out. Again, this is something which affects many industries, not just graphic design. However if women are less comfortable with self-promotion generally, it can be difficult to persuade them to actually participate in these various events. Perhaps this is something which needs be addressed in design education, with presentation and self promotion skills taught by experts and treated as a vital part of the curriculum, with marks going towards the student’s final grade?

And maybe it’s time for more of the many thousands of other women graphic designers to take responsibility for making sure their voices are heard – at conferences, events, and in design magazines and blogs. While it’s boring to constantly talk about being a woman in design (and not just a designer), it’s human nature that the status quo will prevail unless some action, however small, is taken. It’s not a question of favouring women over men, just recognising and promoting their achievements on an equal basis.

There is growing awareness thanks to initiatives such as Women of Graphic Design, Graphic Design Birdwatching and of course Women’s Design + Research Unit (WD+RU). An exhibition A+: 100 years of Visual Communication by Women at CSM and an accompanying Twitter campaign (#CelebrateWomen) both launch today.

Gender is only one aspect covered by Graphic Designers Surveyed, and there are many other fascinating and equally revealing areas to explore within, with sections on clients, money and opinions and a comparison between the UK and USA design industries. For a book without any images, it’s surprising visually engaging, with GD&’s comments adding context and commentary to the facts and figures. It might only represent a glimpse of an industry which seems to be constantly in flux, but it’s an important publication, which like many of the best research projects, raises almost as many questions as it answers.

Find out more about GraphicDesign& here, and buy a copy of Graphic Designers Surveyed here.