Ditto Press’ new book Skinhead: An Archive uses a wealth of printed material and ephemera to explore the multiple – and often diametrically opposite – incarnations of skinhead culture.

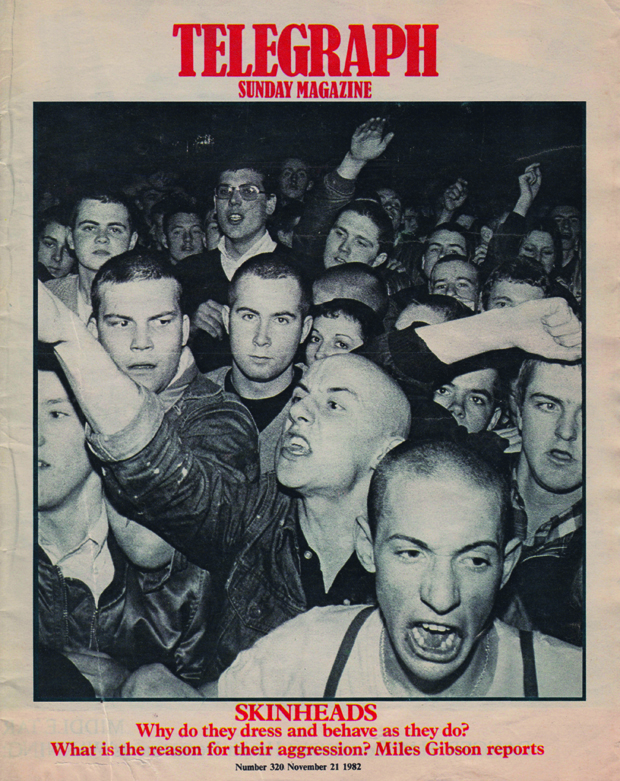

It’s a bold – and important – move to attempt to unpick something as controversial and often inflammatory as the skinhead at a time when the far right is gaining so much ground across Europe. Only last Monday a record 18,000 people joined far-right organisation Pegida in a march through the city of Dresden, with similar xenophobic and nationalist sentiment rippling across the rest of Europe. The skinhead may not be the defining look of these extremists (in fact Pegida have been dubbed the ‘pinstripe Nazis’ by some members of the press), but its power as a signifier of aggression, violence and non-conformist political or social views still packs a punch.

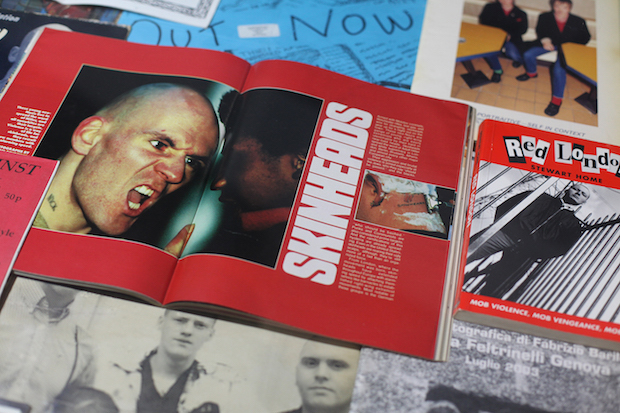

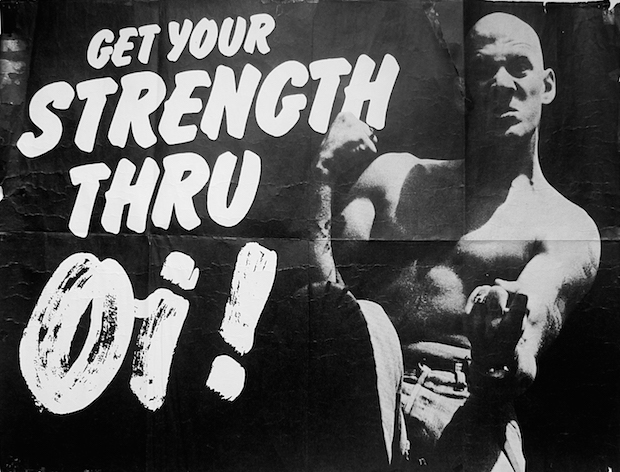

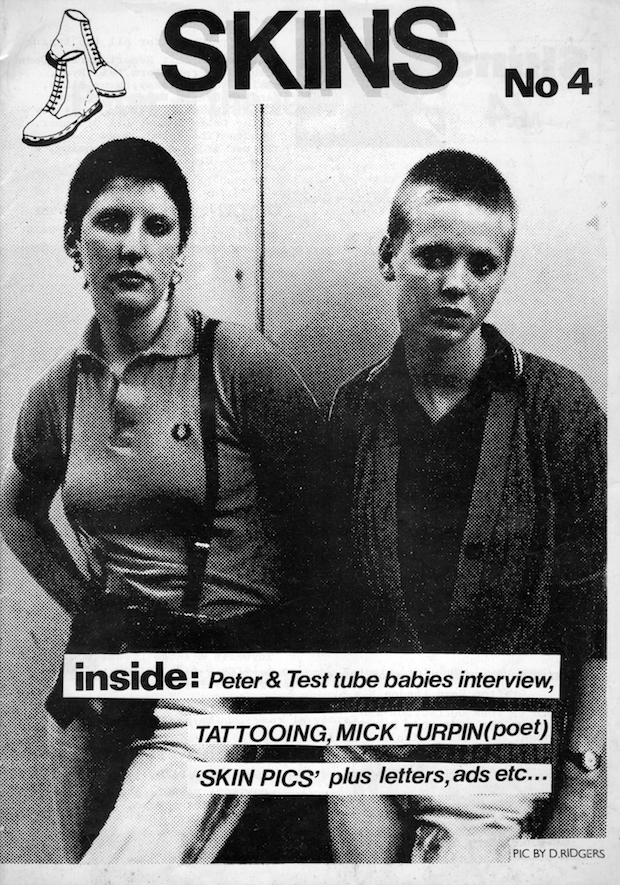

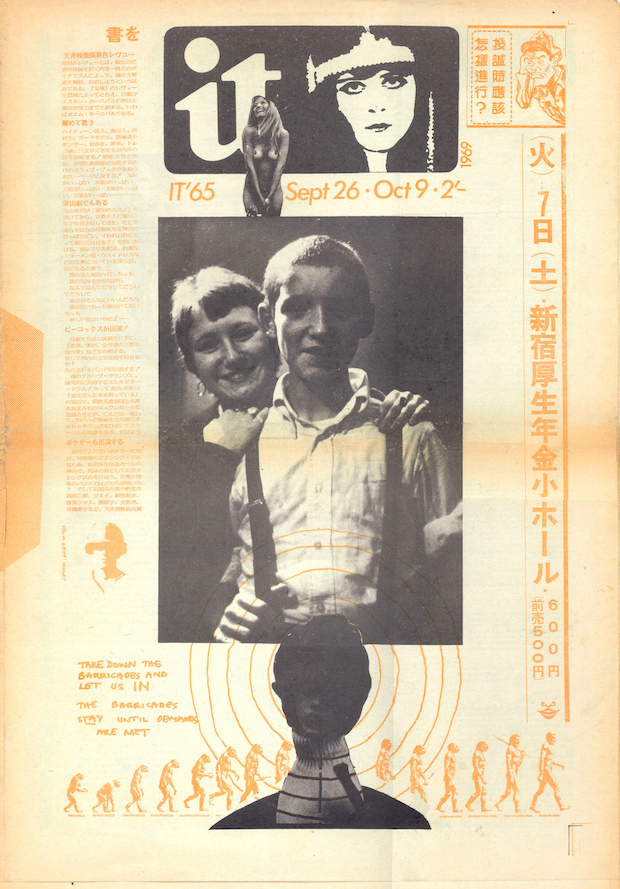

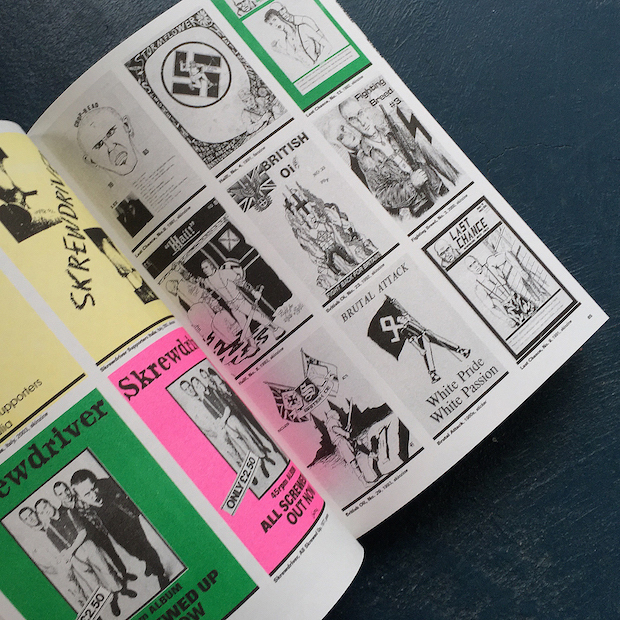

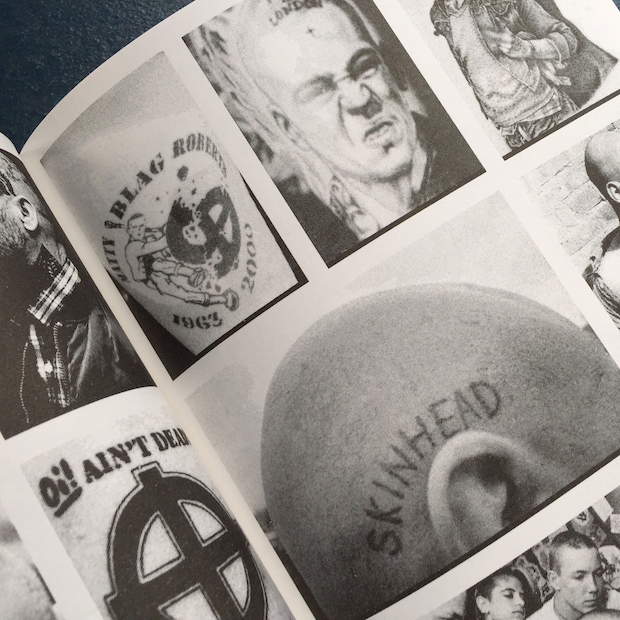

Using archivist Toby Mott’s immense collection of punk and skinhead ephemera, zines, flyers and posters as an access point to discussing skinhead culture more widely, Ditto’s new book Skinhead: An Archive presents the multiple – and often incongruous – incarnations of the movement. These range from its roots as a working class fashion (a harder mod style “which reflected the bleakness they saw in their everyday surroundings,” says writer Garry Bushell in one of the the book’s essays), to its incorporation into right-wing politics, adoption by the left-wing Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice (SHARPS), the softening into suedehead and its appropriation by the gay community (for some “a fetishisation of extreme masculinity, while for others a usurping of strength by the normalisation of an aesthetic”).

Mott has been collecting print materials from music subcultures since the Seventies, and previously curated Loud Flash, an exhibition about the punk scene at London gallery Haunch of Venison, and worked with Ditto on books American Hardcore, 1978-1990 and Jubilee, 2012: Sixty Punk Singles. Unlike these two previous tomes, Skinhead: An Archive has been created independently of The Vinyl Factory, a project two years in the making that signals a new, beefier approach from the Hackney-based publisher. “It's a perfect project for us because it's got substance, it’s not just surface,” says Ditto founder Ben Freeman. “Some of the things in Toby’s collection most people probably wouldn't touch with a bargepole. Some of it's quite extreme. There's something in there to offend everyone, if they wanted to be offended.”

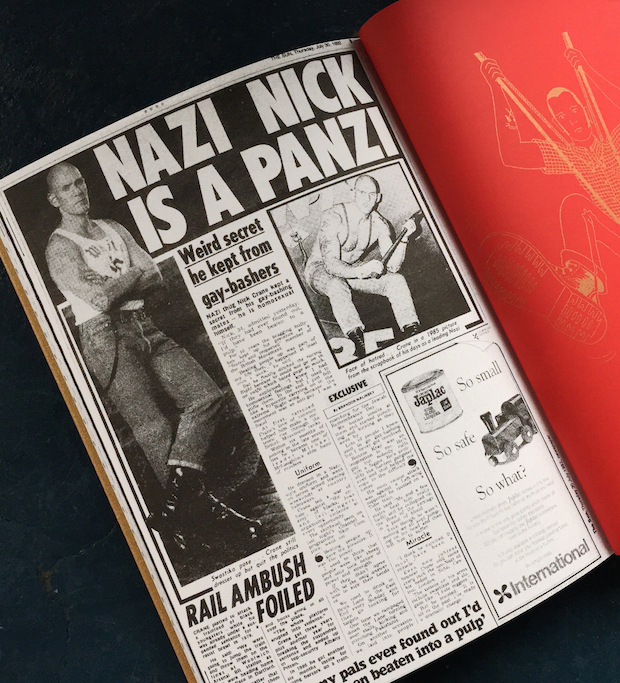

Split into nine sections, the book traces skinhead culture thematically, with an introduction by Mott and essays from the scene’s main proponents and commentators. Rather than approach the subject matter with a revisionist or reductive attitude, the book lays bare the various elements of the skinhead movement warts and all. “I'm a very big proponent of freedom of speech, and in a true sense, not just freedom of speech except when it offends somebody,” says Freeman. “There is some extreme right wing stuff in there but it's seen through the filter of it being an archive. This is history.”

This approach extends beyond the decisions of what ephemera to include, right though to who to invite to pen the essays spread throughout the book. While writers Shaun Cole and Garry Bushell provide more contextual pieces on aspects of the scene they are familiar with (fashion and the movement’s history), Freeman and Mott also asked people like filmmaker Bruce LaBruce, whose work involves gay skin porn and portrayals of sexuality in both the extreme left and right, and Joe Pearce (a former member of the National Front and the editor of Bulldog, the magazine for the organisation’s younger readers) to contribute personal views on skinhead culture. The result is a very balanced gathering of voices, which leaves readers to come to their own conclusions rather than leading them down a particular political corridor.

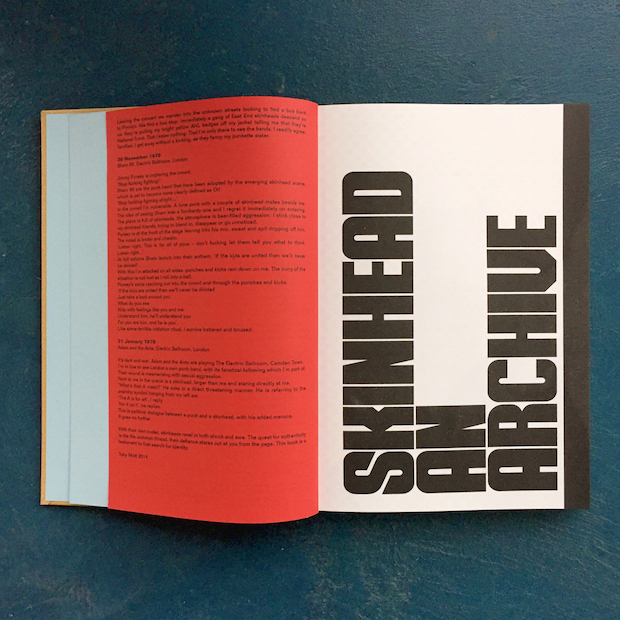

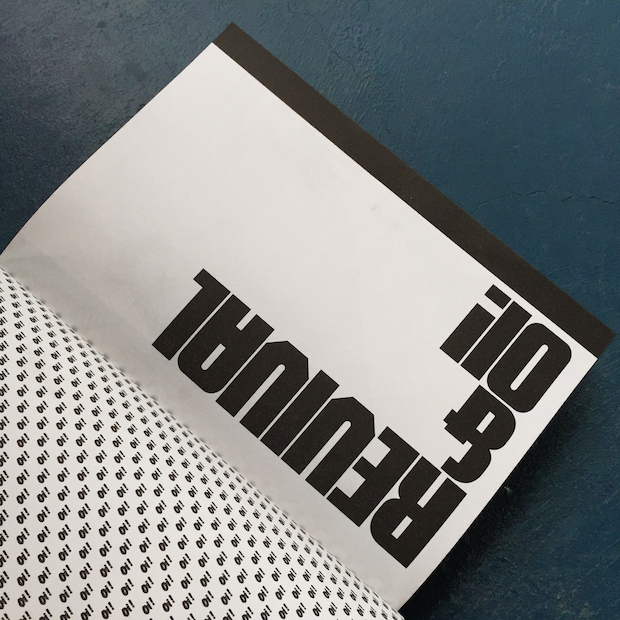

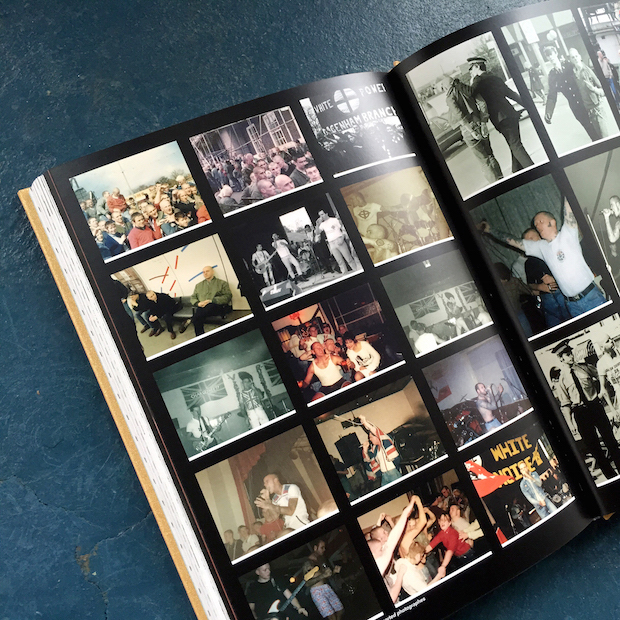

Design-wise Jamie Reid (Ditto’s long-time designer rather than the Reid of Sex Pistols fame) has echoed the book’s aversion to the obvious, shunning a visual language that glamourises aggression or borrows too heavily from the scene’s origins in reggae and Rude Boy culture. Instead, chapters have been divided with simple, yet powerful typographic pages, set in Skin, a font designed by Reid especially for the book (and available to purchase from Ditto) based on a re-drawing of a headline typeface from an article in Penthouse on the skinhead subculture published in the 1980s. Each of these pages is paired with a patterned frontispiece made up from icons inspired by the chapter’s theme. Perhaps a no-brainer for a publisher that started off as a risograph press but incredibly effective nonetheless, the large majority book has been printed in riso (largely in black and white but with carefully chosen one or two-colour highlights) in keeping with the the photocopied, low-cost production of much of the featured material. There is a small offset chapter, which features coloured photographs, DVD covers and the like, introduced where risograph would detract from the power of the original imagery.

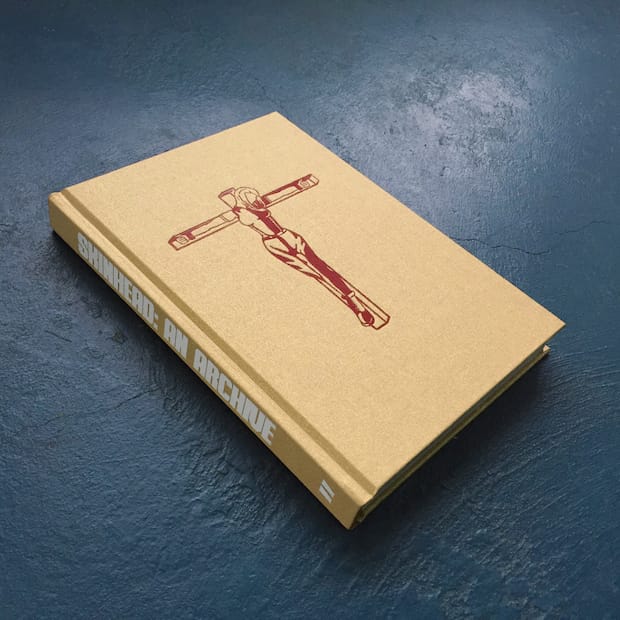

Elsewhere, the essays have been printed on red stock with a narrower page width, a clever way to make a clear visual division between the archive material and contemporary additions. Where the text does not quite fill both sides, Reid has developed a series of stylised illustrations inspired by promotional material for skinhead shop The Last Resort, printed in gold matching the book’s unexpectedly gleaming cover. A similar Last Resort illustration, a skinhead pinned to the cross, has also been used for the cover, adapted from a male to a female figure by Ditto to echo the book’s unorthodox approach. “There's a famous meme within skinhead and hardcore music of people being crucified for their beliefs,” explains Freemans. “It stems from this weird victim mentality within some quite aggressive subculture scenes.”

As Freeman points out, there is something in this book to offend everyone (if they want it), and for me, the only element that triggers a somewhat uncomfortable response is a chapter dedicated to female skinheads called Girl Skins. Despite the chapter being largely comprised of images of skin pin-ups (a cover of the Skinhead Times features a photograph of Noelle Cutler, Miss Skinhead 1993, with the headline “Full Address And ‘Phone Number Inside!”, for example) rather than female activists or such, my issue is not with the objectification of women that the chapter presents (just turn to Queer Skins to see similar objectification of men) but with the omission of a female voice contextualising it. Unlike the Queer Skins chapter, there isn’t an accompanying essay shedding light – whether a personal recollection or a more historical viewpoint – on what it was like to be a female skinhead in an overwhelmingly masculine subculture. Just like the insight that the skinhead was worn by some members of the gay community in support of HIV positive men whose treatment made them loose their hair, I imagine a parallel essay to accompany the Girl Skins chapter would have yielded similarly unexpected discoveries.

On the whole, the book is an substantial, and well thought-out project that uses Ditto’s in-house printing processes innovatively and with real consideration for the archive material. Skinhead: An Archive is a beautiful object and a promising indication of Ditto’s evolution for 2015. Skinhead: An Archive, curated by Toby Mott

Published by Ditto Press, £38

An accompanying exhibition runs at Ditto Gallery until 22 Jan 2015

Skin, a typeface by Jamie Reid, is available from the Ditto shop for £40

dittopress.co.uk