Take a trip into the Grafik archive, to a shed outside San Francisco, where Robert Urquhart found Victor Moscoso— The king of Sixties psychedelic posters recalled that heady era, offered wisdom about ways of working and self promotion

San Francisco, Brighton in the Himalayas, the place where, half a century ago, beatniks turned hipsters under the Californian sun. Victor Moscoso, the old master of psychedelic art, lives just north of the city, in sleepy Marin County across the Golden Gate Bridge. I could pop over in a taxi and go see him in an afternoon.

Sitting by the pool after my arrival in San Fran, I call Victor. “How much is the fee for this interview?” he asks. “There is no fee, Victor, but it’s great publicity for you,” I say. “Jeez, man,” comes the reply, “you’re getting me to do all this work for nothing? Okay. Make sure you buy my book before you come and see me. I’m about an hour and a half out of town. I can give you a couple of hours, I guess.” Thank you, Victor.

A week later I’m sitting in a cab, clutching the book (Sex, Rock and Optical Illusions, published by Fantagraphics in 2005), heading over the bridge with a nervous taxi driver at the wheel. He’s wondering why he’s taking an Englishman into the remote hills beyond the bay. I’m wondering whether he knows where we’re going and what kind of reception I can expect when I arrive.

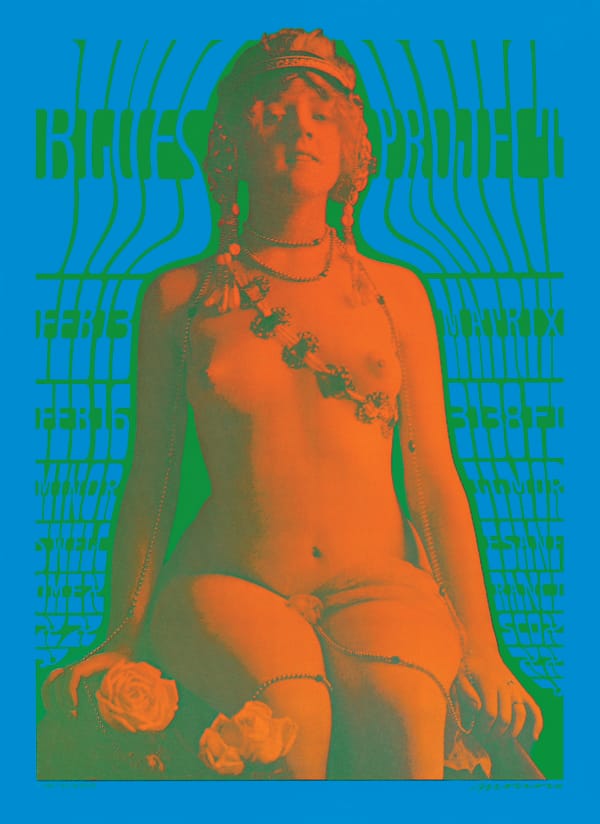

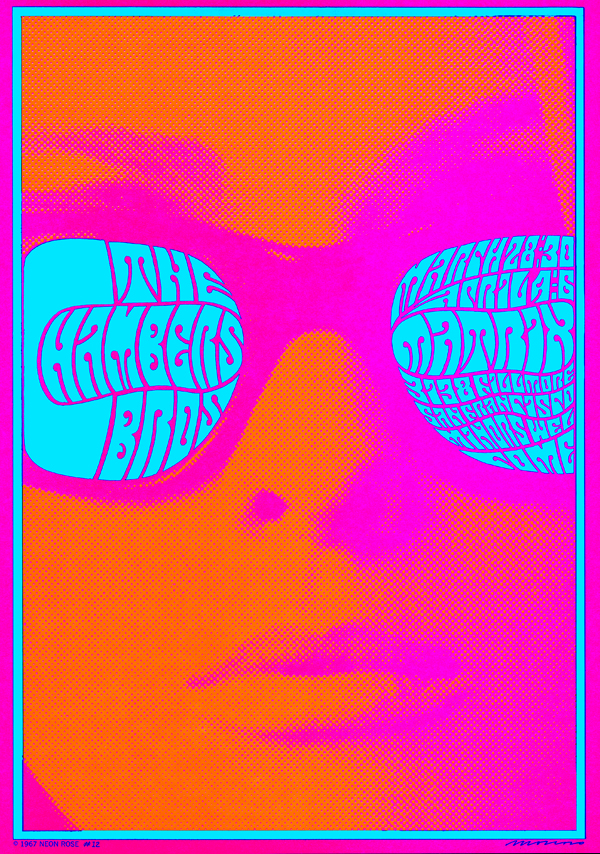

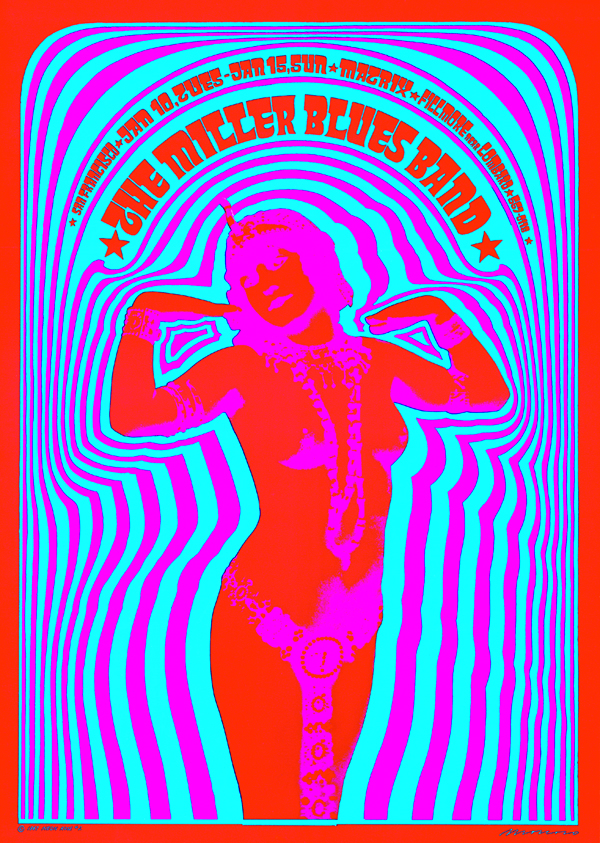

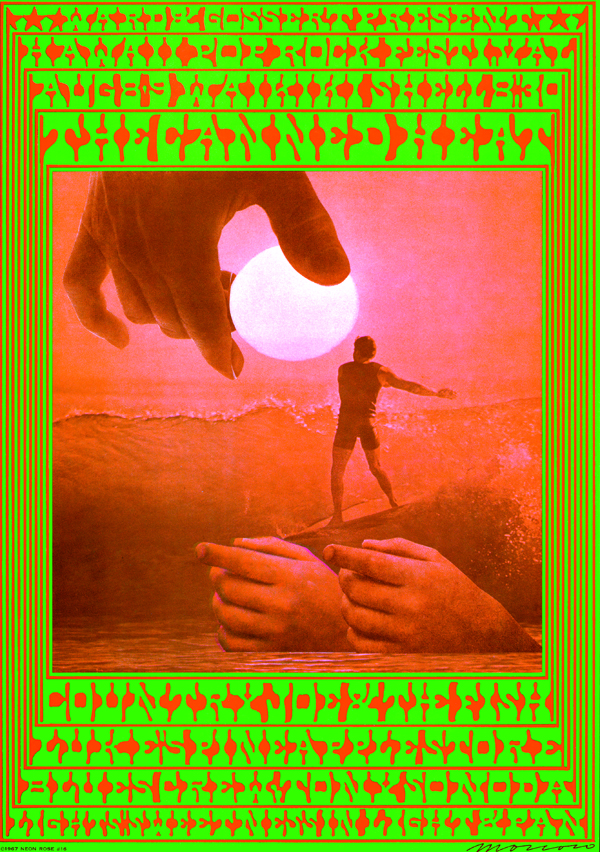

Moscoso, Rick Griffin, Stanley Mouse, Alton Kelley and Wes Wilson were the Big Five of what is now called the psychedelic art movement, producing posters for music venues the Fillmore Auditorium and the Avalon Ballroom for the Family Dog collective. Moscoso was also making posters for his own company, Neon Rose, around the Haight-Ashbury district. From 1966 to 1969, these five ruled. Their works lined the streets, advertising gigs by the Grateful Dead, The Sparrow (later to become The Doors), Jefferson Airplane, Big Brother and the Holding Company with Janis Joplin, Quicksilver and the Steve Miller Band, among countless other legendary performers of the time. Their work was picked up around the world and became the trademark graphic depiction for the music and counterculture of a time. Today, Moscoso is one of the last men standing. His talent is equal to those he advertised. He is a legend. I always treated the job as if I was a plumber. Would you ask a plumber to fit a toilet for free? No. So don’t ask me. I call myself a graphic designer, that’s a practical and useful role in society. As you cross the Golden Gate Bridge from the city, the landscape changes. Marin County looks a little like the Lake District, or more like Devon in the summertime perhaps — lush, green, remote and hilly. The GPS directs us down a steep path into a thicket. Suddenly, from behind a bush, out leaps a tall, dark, bespectacled man in a bandana. He jabs at the window of the cab. This is Victor.

It turns out the bush has a door and the door leads to Victor’s studio. Victor’s studio is amazing. There’s nowhere to sit, it’s stuffed full of drawings, reference materials; bits and bobs. It’s man-shed heaven. I had been filming my arrival on my camcorder but Victor objects. “Hey, what you doing? Put that away. There’s stuff in here that’s not copywritten yet.” Sorry, Victor.

Victor is obviously someone who has a handle on his business matters. As I set my Dictaphone going he also sets his own going, his wonderfully evocative Brooklyn-meets-West Coast drawl announcing the wrong date into the tape recorder. I correct him. He tells me I’ve got toothpaste on my chin. “It’s showbiz, you always gotta remember that,” he reminds me. I like Victor.

“Don’t blame me for being an American artifact, I don’t like it either,” Victor begins, meaning every word. “I’m a poster guy, that’s it.” We begin talking around the psychedelic art label. “The Ninja Mutant Turtles. They lucked out, man. Leonardo, Michelangelo, they had the right idea. Digging up treasure.” I guess he’s talking about commercial art. “Fuck this fine-art shit, man”.

I bring up a quote from Victor at the end of his book — “What is the job? When do you want it? What does it pay?”

“Oh shit, here comes one of those rare guys, an artist that knows about business,” he laughs. “I always treated the job as if I was a plumber. Would you ask a plumber to fit a toilet for free? No. So don’t ask me. I call myself a graphic designer, that’s a practical and useful role in society.” But back in the 60s the term ‘graphic designer’ didn’t exist and the profession was new. Throughout, Victor makes it clear that he was a poster artist: “That’s what we were known as, me, Griffin, Mouse, Kelley, we were the poster guys. There was no other way of communicating about these dance events. No radio, no television, this was the only way.”

He arrived in San Francisco in 1959, from Brooklyn where his family had emigrated to from Spain at the onset of the Spanish Civil War. “Brooklyn is a great place to be from,” says Victor mischievously. Prior to his move to San Francisco, he attended Cooper Union before transferring to Yale. At Yale he studied under the ‘father of Op Art’, Joseph Albers. Albers was a refugee of another war. He had been a student, then a professor in the Department of Design at the Bauhaus in the 1920s and early 1930s. When the Nazi Party gained power in 1933 Albers felt the heat and fled to America. Or, as Victor astutely sums up, “Hitler sent all his non-performing artists to the USA.”

Albers bridged a transition between traditional European art and the new American art on the 1950s and 1960s. This was the first in two points of Victor’s career when he would be “the right guy at the right place at the right time”. The second would not be until seven years later in Haight-Ashbury.

We had more in common with the youth of China than we did with our parents. America was an army state. If your hair touched your collar you’d be expelled from school. Arriving in San Francisco just as the beatnik culture, gestated in his beloved NYC, reached the mainstream public consciousness around the world, Victor got a job as a labourer, “earning three dollars an hour, more than any of my college friends”, he notes. But Victor is dismissive of the beatnik movement, calling them fantasists. There was a more seriously active, more rebellious time to come.

The year of his arrival in San Francisco, America had become engaged in a war that was the catalyst to a cultural revolution and a shift in the thinking and understanding of America as a world power around the world. A war that questioned the American Dream, a war that brought together a generation and divided a nation. Victor was on a different front line. “I got called up by the army, which wasn’t killing anybody yet by then, but still I didn’t want to join up so I enrolled in college. We had more in common with the youth of China than we did with our parents. America was an army state. If your hair touched your collar you’d be expelled from school. Married couples slept in separate beds. We were like ‘we know what you do, man. Christ, this is fucking bullshit.’ America. The country that has brought you the Vietnam War…”

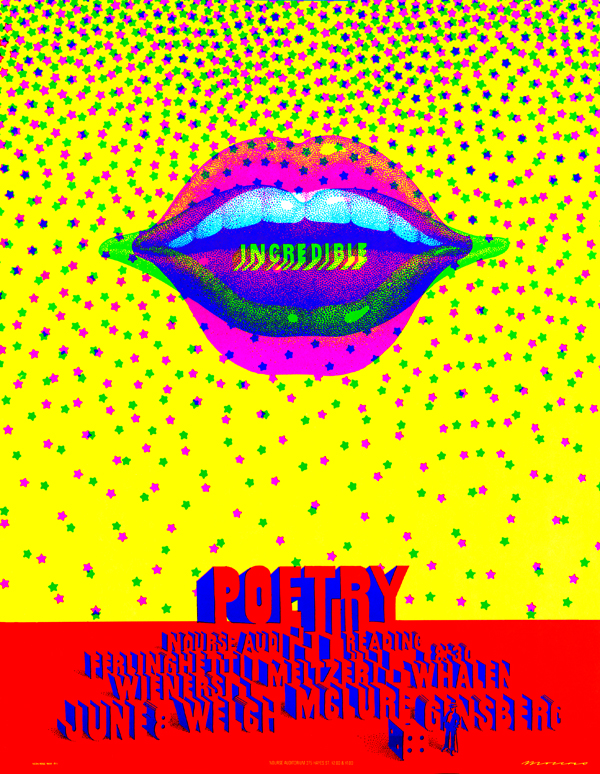

San Francisco was already a magnet for America's counterculture. Beat-generation writers living in North Beach fuelled the renaissance with poetry that quickly took a hold on the bourgeoning music scene. By now Victor was teaching at the Institute for Art, which put him in touch with ‘the scene’ directly. Artists like Alton Kelley and Stanley Mouse were hooked up with music promoter Chet Helms under the title of The Family Dog. Promoter Bill Graham was lurking, ready to muscle in with his hard business ideas. The short-lived, but highly productive period in which San Francisco was to dominate as the most iconic poster art centre of the world was about to begin. Victor saw an opportunity. For the second time in his life he was the right guy in the right place at the right time. “I saw what those guys were doing and I thought ‘I can do this’.”

While the posters Mouse and Kelley produced were heavily influenced by Art Nouveau graphics, particularly the work of Alfons Mucha, Victor remembered the teachings of Albers and that of his own ‘plumber trade’ work ethics. “Within three posters I was in the game. I started my own production company and went to the promoters — who initially said they couldn’t afford me — and said: ‘Hire me and I’ll give you 200 posters, then I’ll print the rest and sell them myself.’ This worked out well, I was selling them for a dollar a print.”

The posters were everywhere. Victor recalls that the San Franciscan police were getting heavy-handed with the hipsters, by now called hippies, beating them up for leaving garbage cans out with the lids off. “The neighbourhood got together and said, ‘Hey, let’s not give the cops any excuse to fight’ so I came up with a poster that simply said ‘Clean Up’. After that I’d go walking down Telegraph Hill and there’d be posters in every window. It was like the Sistine Chapel, man. Wow, I loved it.”

By 1966, the hippies had reached their high. “Sixty-six was the true summer of love,” Moscoso asserts. “George Harrison was right when he said it was shit in 67. The trouble started when the dealer Super Spade got killed — new drugs, new people — just because a guy has got long hair don’t mean to say you should trust him.”

The descent may have started in 67 but it was also the year the Big Five made it really big. Often cited as a pioneering event in the evolution of psychedelic poster art, The Joint Show was held at the Moore Gallery in July 1967. The ‘poster guys’ had an art show and the spotlight was well and truly on them. People spilled out onto the street and hung off rooftops to celebrate the decorators of a revolution. It sounds like one hell of a party.

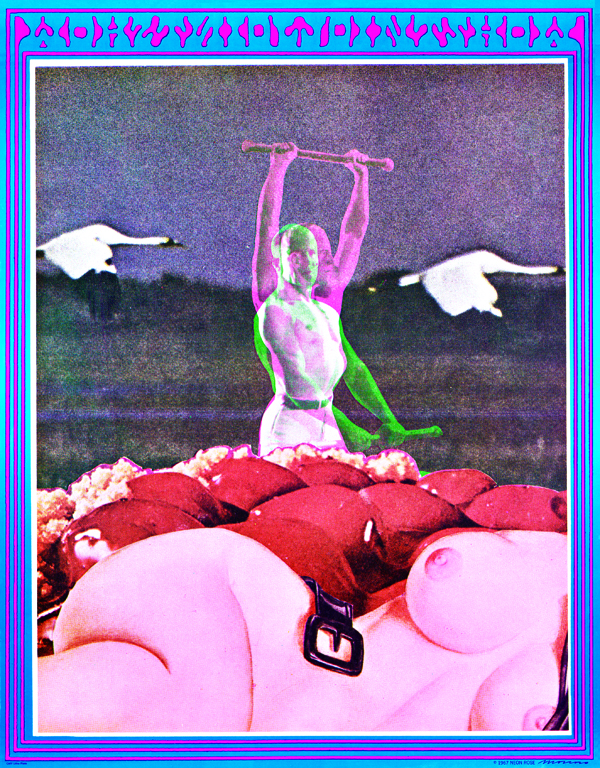

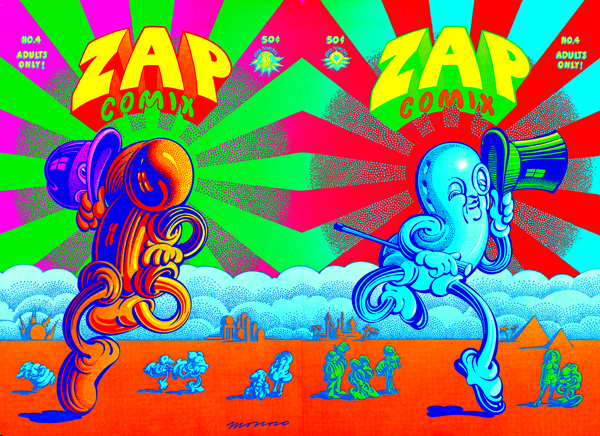

“Holy shit. I had no idea, none of us did,” Moscoso remembers of the show. “We did posters to get people to go to the dance hall. Sure, it got smart, we did it to entertain them, and the information became entertaining. Here I am doing what I want to and getting paid. Goodbye, Van Gogh syndrome.” The Joint Show smoked the butt of the Haight-Ashbury love-in and Moscoso was already pushing things forward again. “By this time I’m starting to get tired of posters, gee, I’m tired of them. I’m with Rick Griffin, he had been a cartoonist before the posters, and we came up with a plan of doing a full-colour magazine. We called it Zap Comix. Griffin ran into Robert Crumb, he adored Griffin’s work, and here we had all this unbelievable iconoclastic imagery. I took over production and Wes Wilson joined in. That nailed it to the wall. Zap 2 comes out and it takes off, selling in every head shop in the States.” Speaking about the triple-X-rated content (including incest and severed penis heads) in Comix, Victor says, “It’s one thing to think it… but to draw it… then to publish it? Wow. Outrage. We thought all the taboos had been broken. Right down the pipes, man, they can’t swallow this one.”

This was the last stand. By now the front line in the alternative war had broken ranks, Bill Graham was creaming money with business deals that were decidedly more self-serving than they were in the interests of the community that had provided the talent. The new drugs of choice — heroin and cocaine — had turned the hippies sour. The war in Vietnam was now, even in the mainstream, an agreed failure. The party was over.

Victor continued working on the fringes producing record sleeves, notably the excellent Headhunters album cover for Herbie Hancock in 1973, and working to demand for a clutch of 60s contemporaries including Jerry Garcia of the Grateful Dead. Victor also continued to teach, primarily teaching students how to use their portfolio to get work, an honourable task and one that is only just beginning to be understood as necessary by art schools even today.

Victor is incredibly humble about his influence and abilities and is refreshingly candid about his generation. “Every generation is as talented as the last,” he says. “My work was about the craft of putting opposing colours together. It had nothing to do with acid — how to you paint the birth and rebirth? You can’t. All I did was say: ‘Hey, go buy a ticket to this, you might get something out of this.’ It’s easy to rebel.”

When I ask about the resurgence of psychedelic art in the 1990s with the advent of technology that produces fractals and the fact that Timothy Leary said that the digital revolution is the new LSD, Victor retorts: “He took too many damn drugs.”

Victor’s love for his craft, away from the strobes and bongos of the dance halls is obvious. He speaks with emotion about offset litho and stone litho techniques, drawing on limestone, the texture and physical work of printing and silkscreening. But it’s time to go. The taxi driver who’s been shitting himself ever since I told him that there were probably bears in this part of the woods is tooting his horn. In the hurry to leave I forget to get my book signed, a regret that hangs over my head.

What was he like? asks the taxi driver as we head back over the bridge. “I just met a master,” I reply. “So go and buy his book, Sex, Rock and Optical Illusion. He’s not a plumber, he’s a decorator and, like Michelangelo in his time, the best in the business.”

There you go, Victor. I sold it. victormoscoso.com

This Profile article was first published in Grafik issue 181, January 2010