Marking the recent release of Aphex Twin’s first album for thirteen years, we hear from his record label Warp and long-time collaborator Ian Anderson of tDR about disinformation, promotional conjuring tricks and working with electronic music's most enigmatic character.

I've laid this whole designer / musician issue to rest, or have I? I've gone to the amplified mouth of the beast. Aphex Twin’s much vaulted return to the world is upon us and I'm in Sheffield to meet Ian Anderson, owner of The Designers Republic (tDR) to talk about his longtime collaboration with Warp Records and his most recent collaboration with the label on Syro by Richard D. James, aka, Aphex Twin.

The first track on Syro is minipops 67 [120.2] (source field mix), an effervescent reprisal of seemingly every sound previously spewed forth by Richard D. James. Ian Anderson is the Maxi-Pop, the equally effervescent patriarchal design figure of techno. I'm sitting at a table with Anderson where, every time we try to talk, a helicopter swoops overhead or a drunk in the background yells out. My field recording turns Warp under the Sheffield sky. I don't really have any interest in getting up in the morning and just designing something. We're talking ‘disinformation’ — “I think that there is a really great synergy, I always use that word, I need another one,” says Anderson. “There's a thing between the way that Richard approaches what he does and the way that I do, in that our motivations for doing it are largely not what you'd expect from someone either making music or designing. I've always loved the idea of disinformation and that idea that there is no one truth, but you can get closer to the truth by discounting the things that aren’t. In some ways, by putting out disinformation, the audience at least knows that that’s not true, or they should do, so it therefore limits what could be true.” Got it?

Such creativity would be worthy of P. T. Barnum — is what Anderson does with Aphex showmanship? “It's all showmanship isn't it?” Says Anderson. “I think that’s just an extension of the creative thing, it’s just playing a game. I don't sit there and go 'how can I confound somebody?' And I don't really have any interest in getting up in the morning and just designing something. I didn't study design, and to me, design is only a means to an end — to me the problem-solving, the communication of the solution and the research… working out what we need to do and how best to communicate that to illicit the desired response: those are the interesting things”.

Warp Records has created a world around sound. Talking to Anderson about the mysterious, discordant beauty in music that resonates with so many people, and his visual input from the very start of the label, brings us around to how he invented a feeling for what techno could look like.

The Warp Records logo that Anderson created twenty-five years ago is not only a product identifier, it's a gesticulation to an idiosyncratic sound beyond techno. “We had a world of Warp and one of the things that we talked about was the fact that they wanted to be seen as modern and slightly futuristic but not with that obsolescence that looks a bit daft, like robot maids and all that sort of thing,” says Anderson. “They were really just starting out on an idea of what the future might be. We also talked about aspirations, they said 'we don't want to be a small label'. It’s funny, when you start out and you've got nothing, it’s, like ‘well why not think big, why not be the biggest label in the world?’ So that’s why I ended up with this flattened Earth and Dan Dare flash — It's a future-proofed, forward-looking icon”.

Did the artwork lead to musicians being attracted to the label because of the uncompromising visual stance? Early releases were nearly always somewhat purple in appearance. “We always pushed a certain scheme: Keep it purple. I know that Tom Jenkinson [Squarepusher], his first thing when he signed to Warp was 'I'm signing to you because I want a record put out in that purple,’ so obviously by that point it was a fact that Warp had got a visual reputation.” says Anderson.

From the logo onwards, tDR has worked with all the Warp Records stalwarts, from LFO to Squarepusher and, perhaps most notably, Autechre. In many ways, tDR has been Warp Records with the sound turned off and the visuals turned up. James Burton (creative services and production manager) at Warp confirms this view of the relationship between Warp and Anderson. “He's a big personality and it’s not about being a designer in a service role for him,” says Burton. “Ian dictates what's going to happen a lot of the time, it’s an internal process for him”.

When I ask about the process of producing the artwork for Syro, Burton tells me, “We've had the album since December. It wasn't one hundred per cent finished at that point, but I started talking to Ian round about that time. Richard specifically asked for Ian”.

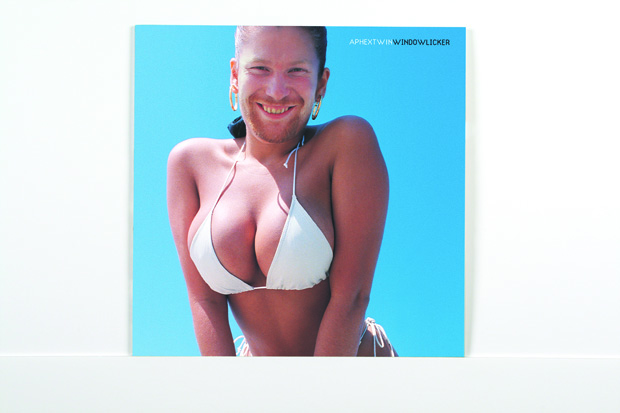

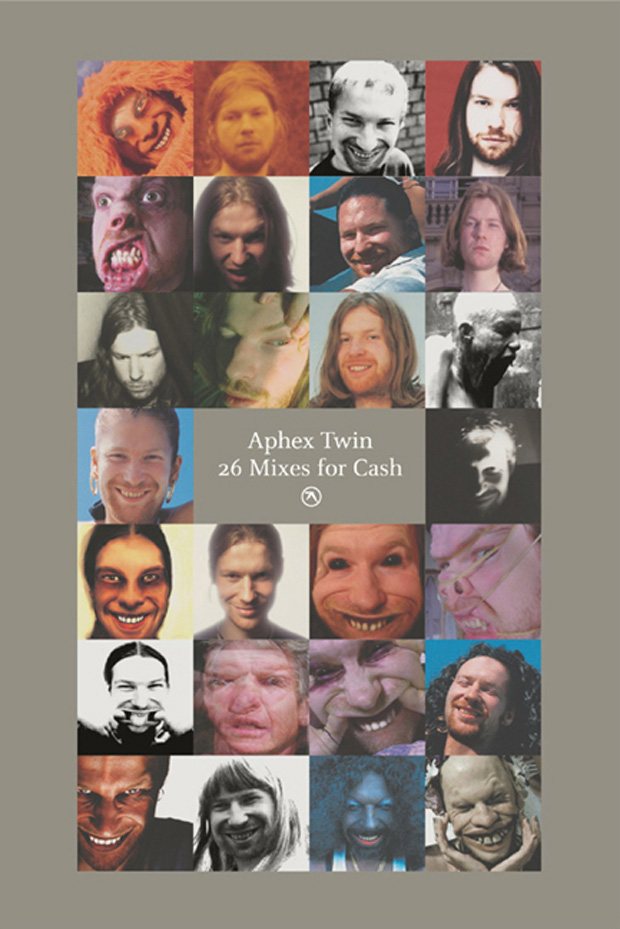

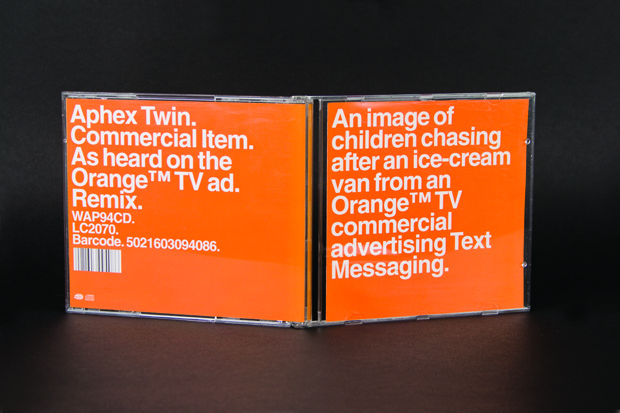

TDR had previously worked on the gloriously and comically disturbing Windowlicker and 26 Mixes for Cash Aphex Twin twin releases. I ask Anderson why Richard D. James asked for tDR to do the artwork this time around. “There were a few reasons I think,” says Anderson. “Richard was close to Rob Mitchell [co-founder of Warp Records with Steve Beckett]. Rob was a friend of mine and when Rob died [in 2001] we had few conversations about that and there was a bit of unintentional bonding. We didn't become best mates, but now, if you think about it, he is part of the old-school at Warp. There are a lot of people there that he doesn't know, but he knows what I'm about and I know what he's about, so it makes sense. We've become middle aged as much as anything else… so I don't think it’s the fact that someone else couldn't do what he wanted, but I think there would be very few people who really understand what he wants to do and why. We come from a certain time, certain influences and experiences”.

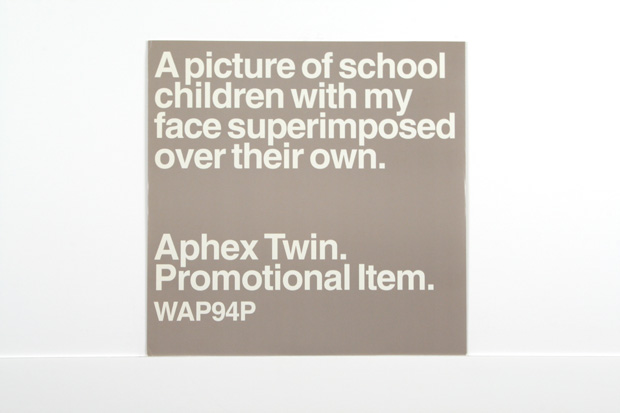

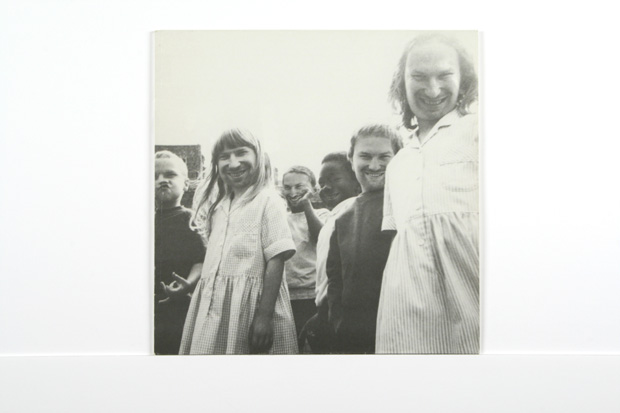

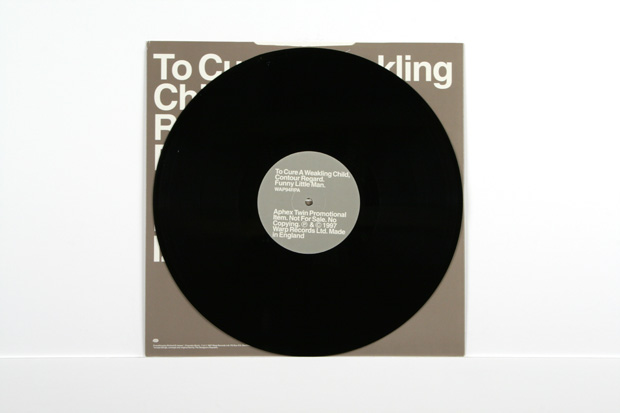

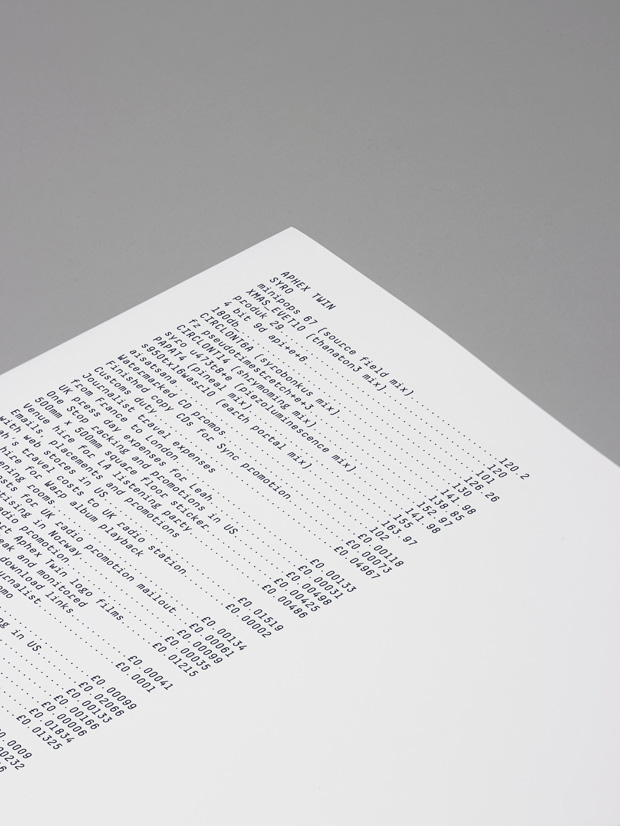

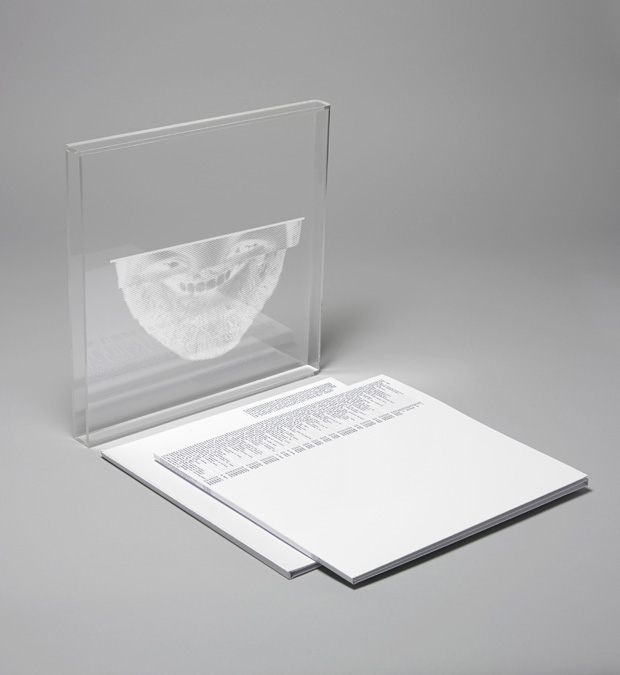

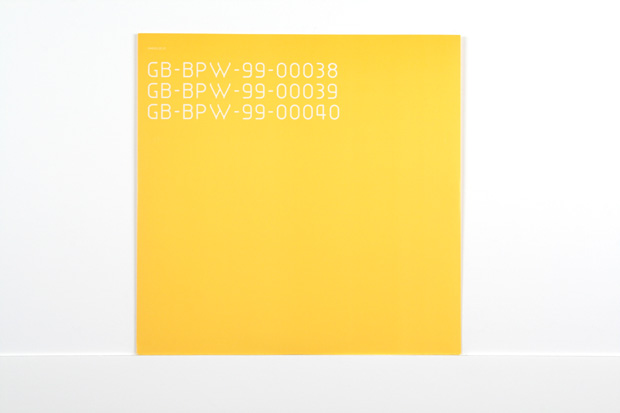

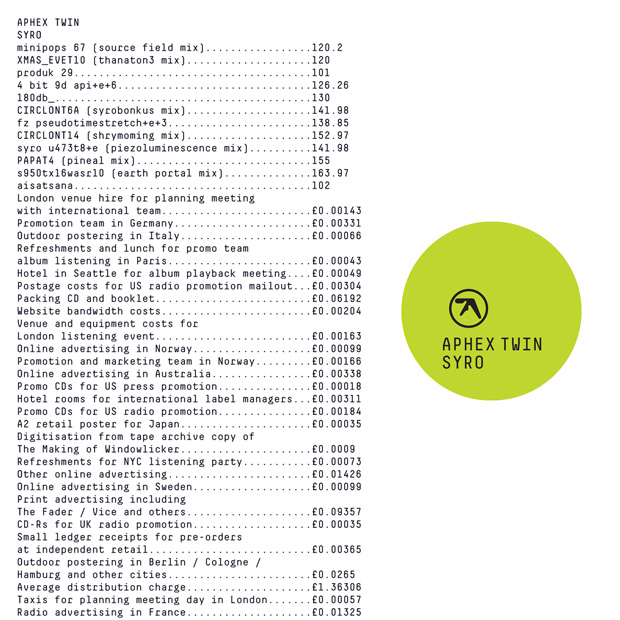

Speaking about the creative process of working on Aphex Twin releases, Anderson explains that James is the driving force behind concepts. “Richard has loads of ideas about what he wants to do, which is why he's done a lot of his own record covers. For Syro he wanted to be able to play the cover, like those old flexi-discs you used to get in Christmas cards… He also had this idea about listing every single cost involved in making the album, which then grew into every single cost of involved in promotion”.

Together, James and Anderson arrived at a rambling inventory of items ranging from courier fees to beer costs for journalists (always an important one). “The conversation about the list was around the fact that it needed to be neutral, not ‘let’s pretend it’s a receipt from a weekly shop,’” says Anderson. “In the end, the decision between me, him and Warp was that the costs listed should reflect the share of the total costs for that single copy.” What was the actual cost? “I don't know, we didn't bother to add it all up,” laughs Anderson. “It might all be a load of bollocks, but to me that’s not important, its how you communicate the thing, the accuracy isn't the important part. I'd love to think that somebody will go and add it all up. And they will, that's what I love about it”.

Picking up on the bloody-mindedness, the wilful obstreperous nature of the music, design and people who make it, I ask Anderson about whether or not it’s over the fact that fans tend to pick over everything that they do. “There's definitely the agent provocateur in Richard and in me. You want to know how much I pay my staff at TDR? It’s half a million quid a year and you can say ‘that’s nonsense’, but there's a reason I've told you that, other than being honest with you. And if you keep asking, you are just going to get another number. In Richard's case, I don't think it’s about exposing himself though what he's doing, I think he knows in the same way that I do, that, okay, 'how can you tell someone everything about this album?’ Well, the sandwiches cost two quid from Pret a Manger. That’s how you make an album”.

Naturally, we return to disinformation. “I like the idea of creating mystique because I think it’s more interesting,” says Anderson. “It’s that idea that questions are more interesting than answers. To me, it’s not a question of trying to keep it underground, that doesn't come into it”. The last thing you could say about Anderson is that he's hiding underground. “One of the the things that attracts us to working with him is that he does have such strong ideas and he delivers them in a non-compromising way,” says Burton. “And, in a way, his voice is heard as much as the artists in some of the stuff we release. That’s both good and bad, that’s the reason we don't work with him on some things — he just wouldn't get on with the artists in some cases”. Everyone in Sheffield either thinks that I'm great, or a tosser. I get the feeling that Burton is talking about some of the newer, less old-school, acts that have made the label since it moved part of its business to a more London-centric operation in the last decade or so. “Most bands that signed to Warp wanted to work with tDR,” says Anderson. “But then, as Warp got bigger, we had conversations about it — what Rob [Mitchell] and Steve [Beckett] said was right, you can't maintain being a label that is more important than the acts for more than ten years because people will get tired of it. Steve's ambition was to be more like EMI, so they signed Maximo Park, that was part of the process.”

Did Warp Records and tDR have an identity crisis? “I think with Warp there was a definite decision where they decided that for Warp to continue and for them to continue they should diversify. If you look at labels now that only ever put trance stuff out, they're no longer going, or they’re producing techno that drives you into a cul-de-sac.”

And tDR? (The Designers Republic faced bankruptcy in 2009, before restarting at the first opportunity). “The music industry, in terms of income, shrivelled up for us. We were still really busy and because I'm not really a businessman I didn't notice, but we'd got some accounts through that said ‘you're not going to be here in a month or two months if you carry on like that’. But we were doing a lot of stuff that wasn't music business. We were doing stuff like Pringles ads, but no one gets excited about Pringles. We got excited because it was something different to apply our approach and attitude to, but these days we do a lot more cultural stuff as well”. I've got a low boredom threshold, there's no point in holding back. Alan Fletcher said that design should be invisible, I disagree. TDR has been back for some time, Pringles are placed as highly as music and culture on the shelf, Anderson seems happy and as thoughtful as I imagine he was before the blip; he rode the (sine) wave and life goes on.

Would he like even more acclaim than he has? “Yeah probably,” laughs Burton. And there is more laughter when I ask him who would play Anderson should there ever be a 24 Hour Party People-esque film based on the techno scene — no one can imagine who could play the maverick design renegade.

Is Sheffield the Hollywood for techno? “I don't think it’s about Sheffield anymore,” says Anderson. “I'm not going down the ‘it's a global village man' route, I think it is the place that’s allowed people like us to do what we do, but everyone in Sheffield either thinks that I'm great, or a tosser”.

Why do people think Anderson is a tosser? “People do, don't they?” he reflects. “I call it the Duran Duran factor: You know when you're successful when as many people hate you as love you. The thing that remains a constant is me — I've got a low boredom threshold, there's no point in holding back. Alan Fletcher said that design should be invisible, I disagree”.

I ask Anderson his thoughts on why so many great designers of our time are influenced by musical ambitions. “I set out to entertain myself,” he says. “I couldn't play bass and writing poetry isn't good if you want to be visible. All good creatives have something to say; you are creative because you have ideas, it’s that self-confidence – if you are a designer, or a musician, you should be in there”.

Anderson, Warp and Richard D. James are all visibly ‘in there’ with ideas, disinformation and mythology. Their desire to communicate the effervescence of their craft brightens up the cultural landscape, and Syro is the latest illustration of this; a blimp on the horizon. Believe in this, and you'll have got closer to the truth.